Introduction

Welcome to Forum 52. This issue contains reviews of two recent SUES activities. Christine Vasey reports on Julia Clayton’s talk on The Fiction of Forgery: Art and Authenticity in the English Novel. Jill Newsham provides a review of Roger Mitchell’s recently-concluded course on Colonial and Post Colonial America – History, Art and Architecture.

Roger has followed up on a subject introduced in the final lecture of his course, with an article on the relationship between Thomas Jefferson, the Third President of the USA, and Sally Hemings, an enslaved woman. This 2-part article will conclude in the April edition of Forum.

Chris Nelson

Coming up in March 2024

Talk by Stephen Lloyd

Shakespeare, the Earls of Derby and the North West

Friday 22nd March at 2:30 pm. All Saints Church Hall, Park Road, Southport, PR9 9JR.

Dr Stephen Lloyd FSA has been Curator of the Derby Collection at Knowsley Hall near Prescot since 2012. He is an authority on the study of British 18th century portraiture, particularly portrait miniatures and the work of Sir Henry Raeburn RA.

This talk focuses on the Stanley family, particularly the 4th, 5th and 6th Earls’ close connections with late Elizabethan and Jacobean performance, theatre and masque culture at Lathom House, near Ormskirk, and at Knowsley Hall. It will also feature recent findings in the Stanley family library and archives and from the conservation of paintings and other items in the Derby collection. These discoveries will be placed in the broader context of the Stanley family’s residences, households, the playhouse in Prescot and their London houses, discussing the theatre patronage that forms a cherished part of Stanley history. This in turn forms a backdrop for the building and opening, in 2022, of the Shakespeare North Playhouse in Prescot.

The Next SUES Course

Alan Potter’s course on Technology – Understanding Just How Things Work! commences on 8th April. There is still time to enrol by contacting Rob Firth by email at suesmembers74@gmail.com.

Meeting Report:

The Fiction of Forgery: Art and Authenticity in the English Novel

by Julia Clayton, 23 February 2024

Those of us who are fans of Fake or Fortune rather like to imagine ourselves as ‘not too bad’ at spotting a forgery. After all, we have seen Fiona Bruce and Philip Mould in action. We understand the importance of establishing a provenance and scanning auction catalogues. We have witnessed the wonderful effect of removing layers of brown varnish. We have seen, via x-rays, underpainting, “The hand position had been moved!”, “This paint sample is authentic but that paint wasn’t invented until the end of the 18th century”, and so on and so forth. We have sat on the edge of our chairs, biting our nails, waiting for the denouement that never fails to increase anxiety and raise blood pressure. Fiona and Philip and all the interested participants await the arrival of a world art expert who will pronounce the verdict on a long-neglected painting found in the housekeeper’s room at a rundown stately home, the owners of which are hoping that, if this picture really is a Caravaggio, they will be able to afford a new roof for the west wing. It’s more likely to be a copy, or a fake. If so, they will just slink away, bitterly disappointed.

Julia Clayton, in her excellent lecture on forgery in art and fiction, filled in many gaps in our knowledge and revealed to us, in considerable detail, the murky world of art forgery. She started not in Rome or Florence but in Bolton, home of British artist and forger, Shaun Greenhalgh, who used his incredible artistic talent to produce fake art treasures which he knocked up in his garden shed and succeeded in fooling international art experts for over ten years.

His most memorable coup was selling what he claimed to be the 3,300-year-old alabaster statue of an Egyptian princess, daughter of Pharoah Akhenaten and Nefertiti. He sold her to Bolton Museum for almost £500,000 of public money and the princess was given pride of place in the museum. Nowadays, she is in a rarely-visited dingy corner. Shaun was eventually caught, prosecuted and jailed for four years. Many of Greenhalgh’s forged items have been recovered, but there are probably quite a few of them still in circulation. Perhaps the most unlikely turn of events for Shaun came after his release from prison when he was invited to appear on Fake or Fortune and, under the watchful eye of Fiona Bruce, produced an L S Lowry forgery.

The other notorious forger Julia introduced to us was the Dutch artist and portrait painter, Han van Meegeren. Negative criticism of his work drove him to prove his talent by forging paintings of the Dutch Golden Age. He used original 17th century canvases and mixed his paints from traditional raw materials, lapis lazuli, white lead, indigo and cinnabar to ensure authenticity. His beaver hair paint brushes were typically used in Holland at that time.

In 1937, he painted Vermeer’s The Supper at Emmaus and sold it for a large sum of money. His subsequent forgeries also sold well, which enabled him to buy numerous properties and land. During the German occupation of Holland, Hermann Göring acquired the Vermeer forgery Christ with the Adulteress.

In August 1943, Göring hid his looted art collection in an Austrian salt mine where it was discovered by the Allies in 1945. Van Meegeren became a national hero for having deceived the Germans, but he was also prosecuted for being a Nazi collaborator who had sold national treasures to the enemy. In order to prove his innocence, he painted Young Christ in the Temple in the courtroom in the presence of the judge and the jury. The collaboration charge was dropped but he was found guilty of forgery and fraud and sent to prison for one year. His assets were also seized and auctioned off to reimburse those who had bought his forged works. He died before his sentence began. After his death, van Meegeren‘s work fetched high prices and, ironically, his faked paintings were faked by other forgers. Van Meegeren’s son, Jaques, also faked his father’s work. The style was the same but the quality was not!

So, how do forgers succeed in hoodwinking the arts establishment? According to Julia, there are three main reasons:

NEED There is a gap in their collection which they want to complete. Van Meegeren claimed that his forgeries were produced in a decade when Vermeer hardly painted anything.

SPEED The necessity of acting quickly in case a rival collector jumps in before you do.

GREED The prestige conferred by the possession of the work of a great artist.

Julia also referred to the questionable circle of dealers who surrounded Bernard Berenson in the early 20th century, when he was the western world’s most influential art critic and connoisseur of the Italian Renaissance. Despite his undoubted learning and scholarship, his reputation has become rather tarnished since the revelation that, if offered a large enough bribe, Berenson would be prepared to give a painting a misattribution.

Julia also showed us how the world of forgery provides a very wide variety of scenarios for the novelist; Patricia Highsmith, Peter Carey, Paul Watkins and Jessica Burton to name but a few. It is a popular recurring theme which can be applied to any number of contexts from crime to romance, to mystery, to historical settings and many more.

So thank you, Julia, for your fascinating lecture which was very well received. We all hope that you will return to SUES in the not-too-distant future and once again educate and entertain us in equal measure.

Christine Vasey

Course Review:

Colonial and Post Colonial America – History, Art and Architecture with Roger Mitchell

Just when we needed something to banish the winter blues, we were cheered by the start of Roger Mitchell’s course on the 8th of January. It was good to meet again all the people who had been on Roger’s marvellous course on the Art and Architecture of the American West last year, as well as quite a few new faces.

Roger did point out that, in view of the previous course, from a chronological point of view we were tackling the topic of American art in the wrong order. He also mentioned that even though our time span was from the 1580s right up to the middle of the 19th century, we would never venture more than 150 miles inland from the east coast of America.

Having established the structure of the course for the next eight weeks, Roger gave us comprehensive details of all the resources we could use to support our further research, or homework as he called it. This year, we had an extra resource, which I found particularly useful: after each talk, he sent us a copy of all his slides for the week via WeTransfer.

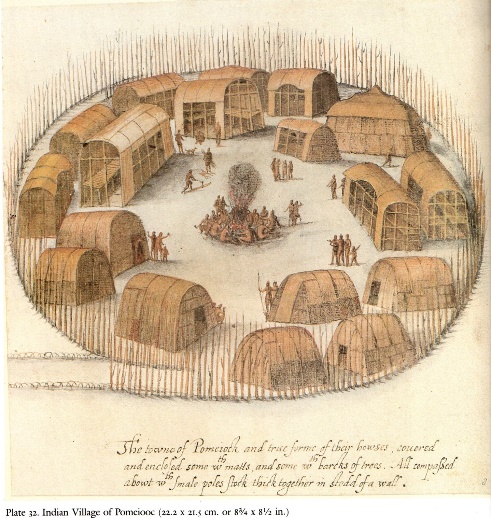

We began by looking at the chronology of the first Europeans to arrive in America, who visited and who settled. It was interesting to reacquaint ourselves with the main characters, in no particular order: Columbus, Drake, Raleigh, Cabot, Ponce de Leon, Cartier and Granville. We ended the first week by looking at the amazing drawings of John White, an Englishman who was commissioned in 1585 to “drawe to life” the area’s native population and natural bounty, which gave us a glimpse of the lost colony of Roanoke.

In the second week we concentrated on the first European settlements looking briefly at the Roanoke project in Virginia and, in more depth, Jamestown in North Carolina. Roger had usefully designed a report card for both settlements to identify the factors, including situation, timing of arrival, the quality of the settlers and their leadership, the level of support that they received from England and their relationship with the native Americans, all of which were crucial to the long-term success or failure of the settlements. It soon became apparent how important tobacco was to the economy and survival of the settlers, which in turn led to an ever-increasing demand for labour. This was answered in several ways, firstly and unsuccessfully by using the indigenous Indian population, who died in huge numbers from imported disease, or who simply ran away. The introduction of indentured labour from England followed and, from 1619, the first slaves from Africa arrived in the Colonies.

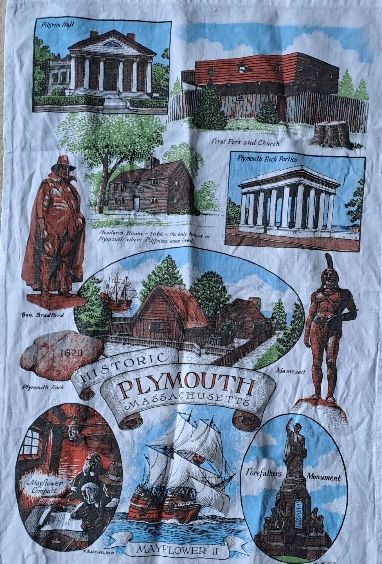

Roger had mentioned in his introduction that he was planning to use different visual aids for this course, but we never expected the tea towel depicting the Plymouth Settlement that was coincidentally found in the kitchen of the Church Hall in the third week. The tea towel fulfilled the brief perfectly in depicting all the important buildings of the Puritan Settlement of Plymouth from 1620.

The title of week four’s session was Society, Art and Architecture, and the changes that had come about due to the population growth which followed the Great Migration of the 1640s, also supported by a higher birth rate, a lower death rate and a generally healthier and more prosperous environment for the residents of the five ‘middle colonies’. The architecture of the houses was mainly influenced by abundant and locally available materials such as wood, used for shingles and roofs, and bricks made from the clay deposits nearby. Sawmills could be powered by fast flowing rivers, but stone and hardware, such as tools, lead and nails, were expensive imports from England.

Having looked at the early architecture, we moved on to what Roger described as the “heart of the course”, examining the lifestyle and culture of the colonial American towns in the 1660s as evidenced by the town, suburban and plantation houses. We examined four houses in Annapolis, Maryland in detail and especially noted the work of William Buckland (1734-1774) who was born in Oxford, came to America as an indentured servant and is credited with being a key provider of Palladian architecture in America. William Nicholson (1655-1728), who was at different times Governor of both Maryland and Virginia, was responsible for the city plans of both Annapolis and Williamsburg. Thanks to Roger’s photographs and an engraved plate discovered in the Bodleian Library in Oxford in 1929, we were able to understand the situation and layout of the original streets and buildings.

The fact that Roger had visited most of the places that he was talking about, and the way that he used his own photographs to illustrate his points, really did make the difference. This was particularly evident when looking at the architecture of the colonial towns and his personal impressions of the reconstructed town of Williamsburg, Virginia.

From the capital cities of Annapolis and Williamsburg we moved on to what Roger called the “visionary” cities of New Haven and Savannah, notable for their formally designed grid pattern layout of streets. Boston, however, was a complete contrast,’ with a layout which evolved from its role as a working port. In 1700, Boston had a population of 7,000 but by 1790 it had descended to third place with a still large population of 18,000, but behind Philadelphia with 28,000 and New York with 33,000. Boston was, however, the home and business place of the Boston merchant aristocracy, the ‘Boston Brahmins’.

A famous piece of contemporary doggerel, The Boston Brahmins or the Boston Toast by John Collins Bossidy, reads as follows:

And this is to good old Boston,

The home of the bean and the cod,

Where Lowells speak only to Cabots,

And Cabots speak only to God.

Both the Lowells and the Cabots were amongst a group of self-proclaimed elite families, the aristocracy of Boston. They were merchants, ship owners, lawyers and industrialists, who played their part in the early government of America, and continue to do so up the present day. They and their fellow Brahmins were rich and powerful and they wanted to be recorded as such, so they commissioned portraits, which were all the fashion at the time, of themselves and their families by artists such as John Smibert (1688-1751), Robert Feke (c1705-1750), Benjamin West (1738-1820) and John Singleton Copley (1738-1815).

The American War of Independence lasted from 1775 to 1783 and, by the standards of European wars of the same period, it was a small war involving less than 20,000 combatants, but for America it was pivotal. In week seven we looked at the causes, events, and consequences of the war and especially at the men, and just two women, who were to play a part in the future of the country. In terms of art, there was a move towards history painting, considered the highest form of art at this time. Artists such as Benjamin West, John Singleton Copley and John Trumbull (1756-1843), painted huge pictures which recorded the epic events that led to the birth of the new nation. They adorn the walls of the important government buildings still. George Washington (1732-1799), the first President of the United States of America, became something of what we might call a cult figure today, with his image appearing in many different forms of art from sculpture to silhouettes.

In the final week, the focus was on the great Americans, their houses and their memorials. There were virtual visits to George Washington’s Mount Vernon and Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello, all enhanced by Roger’s original photographs. Just the names they chose for their homes: Montpellier (James Madison), Highland (James Monroe), Hamilton Grange (James Hamilton) and The Hermitage (Andrew Jackson), give an insight into their origins and how they regarded their legacy to American history.

Thomas Jefferson left a huge architectural legacy which can still be seen in some of the state, government and university buildings of America. He was a strong advocate of classical architecture and maintained that “well designed public buildings would be proof of national good taste”.

Finally, we returned to art and the work of Edward Hicks (1780-1849), a Quaker minister who was notable for his painting, Peaceable Kingdom (1830-2). The painting was a representation of the messianic prophecy in the Book of Isaiah 11:6 “The wolf shall dwell with the lamb” which for Hicks represented the rift within the Society of Friends in the 1820s. It was Hicks’ favourite theme, and we know this because 62 versions of this painting survive until today.

It was not until the 1850s that America’s first independent art movement, known as the Hudson River School, emerged, influenced by the English-born artist Thomas Cole (1801-1848). The artists painted landscapes that reflected the natural majesty of the environment of the Hudson River valley.

Sadly, we had reached the end of an absolutely fascinating course, but there was just one more painting and it had to be by Thomas Moran (1837-1926), who I know is Roger’s favourite American artist. Ironically, after all our travels through the Colonies, this picture Cliffs of Green River (1874) was a favourite subject of Moran’s precisely because, for him, it represented a landscape untouched by colonisation or industry.

Although, it is impossible to cover all the eight weeks in such a short review, I hope that I have managed to capture the essence of what was a truly enjoyable and fascinating course. I feel that I have learnt so much about a period which was, before, just a list of dates and wars. Thank you so much Roger, and I am counting down the time to your next course already.

Jill Newsham

Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings – Part 1

Preparing for my recent course on Colonial and Post-Colonial America has reminded me just how remarkable a group of people the Founding Fathers were. Born as British subjects on the fringes of European civilisation, and only able to get to Britain and Europe by an uncomfortable and dangerous sea voyage lasting anything up to two months, they nevertheless were very much part of ‘the age of enlightenment’. Benjamin Franklin, George Washington and Thomas Jefferson are guaranteed a place on any list of great lives and Alexander Hamilton, John Adams and James Madison would not be far behind.

Thomas Jefferson has a good claim to being both the most talented and the most complicated of the Founding Fathers. Addressing a meeting of all living Americans who had been awarded the Nobel Prize, John F Kennedy described the occasion as the greatest gathering of talent that the White House had seen since Thomas Jefferson dined alone. Jefferson was both a political philosopher and a practical politician. He was at various times President, Vice-President and Secretary of State. He was also Governor of Virginia and Ambassador to France as well as being the founder and the architect of the University of Virginia. He was a distinguished amateur architect and botanist and he corresponded with many leading philosophers and scientists in both America and Europe.

Both his personality and his way of life were complicated and being an inhabitant of 18th century Virginia was a key factor in this. Virginia’s economy was based on slavery and the slave population grew throughout the 18th century. The 1790 census reported 442,000 free whites and 293,000 slaves in Virginia, which had the largest population of any of the 13 states. The situation was very different in the three states that had the next largest populations. In New York, even though 6% of the population were slaves, the tide had turned, slavery was coming under attack and numbers declined before slavery in the state was abolished in 1827. Both Massachusetts and Pennsylvania acted more swiftly with gradual abolition beginning in the 1780s, even though the 1790 census shows that there were still 3,737 enslaved persons in Pennsylvania. However, that was less than 1% of the state’s population and gradual abolition could be achieved without economic disruption.

In Virginia, abolition, even gradual abolition, was never on the agenda. Jefferson, Washington, Madison and other Virginian founding fathers were probably genuine in hoping that the ‘peculiar institution’, as slavery was euphemistically labelled, would somehow disappear, but they took few practical steps to achieve this and all of them made extensive use of slave labour on their estates.

All this is by way of preface to the particular relationship between slave and master that I want to examine. I will not even try to understand how Jefferson could write, as he does in the Declaration of Independence, “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness” and yet continue to hold slaves. Instead, I want to look at the long-lasting relationship between Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings. This began in Paris, probably in 1788 or 1789 when she was 15 or 16 and he was a widower in his mid-forties. The youngest of their 6 children (4 of whom survived to adulthood) was born in 1808. Sally remained at Monticello, Jefferson’s plantation, with their children until Jefferson’s death in 1826. She was subsequently ‘given her time’ (i.e. informally freed) by Jefferson’s legitimate daughter and spent the rest of her life in Charlottesville where she died in 1835 at the age of 62.

There were contemporary rumours of this relationship and of the children that it produced, but Jefferson privately denied them and throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, most Jefferson scholars took the view that there had been no sexual relationship. A guidebook to Monticello published in the 1980s concludes as follows. “This story continues to capture the public imagination. Although it is impossible to prove either side of the question, most Jefferson scholars discount the truth of such a liaison.” In suggesting that we would never know the truth, the author failed to take into account the progress of modern science, particularly genetics. DNA testing of descendants has now provided reliable evidence and, having commissioned extensive research, historical as well as scientific, the Thomas Jefferson Foundation, which runs Monticello, has reached a very different conclusion. Its website now provides the following summary. “Sally Hemings had at least six children fathered by Thomas Jefferson. Four survived to adulthood. Jefferson freed all of Sally Hemings’s children – Beverly and Harriet left Monticello in the early 1820s; Madison and Eston were freed in his will and left Monticello in 1826. Jefferson did not grant freedom to any other enslaved family unit.”

There has been no attempt to sweep this under the carpet, and the Thomas Jefferson Foundation deserves credit for the professional and scholarly way in which it has dealt with a complex and potentially controversial issue. In 2018 a permanent exhibition opened at Monticello with the following introduction.

“THE LIFE OF SALLY HEMINGS

Daughter, mother, sister, aunt. Inherited as property. Seamstress. World traveller. Enslaved woman. Concubine. Negotiator. Liberator. Mystery.”

The use of the word concubine is interesting and is appropriate for two reasons. Firstly, because it has a clear, legal meaning. It defines a woman who has sexual contact with a man to whom she is not married. A concubine has no legal or social standing and her offspring could not inherit from their father. If their mother was a slave, then offspring were slaves from birth. A second reason for using ‘concubine’ is that the word was in common use in 18th and 19th century Virginia. It is used both by Madison Hemings, one of the sons of Sally Hemings and Thomas Jefferson, and by the journalist, James Callender, in an 1802 article intended to defame Jefferson.

The exhibition introduction continues with the following paragraph. “Sally Hemings (1773-1835) is one of the most famous—and least known—African American women in U.S. history. For more than 200 years, her name has been linked to Thomas Jefferson as his “concubine”, obscuring the facts of her life and her identity. Learn more about this intriguing American.”

I am not convinced that the links with Thomas Jefferson ‘obscure’ the facts. The main problem is that the available facts only enable us to gain a limited knowledge of Sally and her life. We get the basics – dates of birth and death for her and her family and their descendants, together with some information about her life from later writings based on material supplied by one of her sons. We have nothing from Sally herself and it is not clear whether she was literate, although her role as lady’s maid to Jefferson’s daughter and their journey to France meant that she would have had a much wider experience of the world than most of her contemporaries, whether they were white or black. We have no letters from or to her and she is never mentioned in Jefferson’s extensive correspondence. The two questions to which we would most like to have the answers are probably these.

Was she loved and did she love?

Was he ashamed, indifferent or just confused?

I had better not say that we will never be able to find answers, but the chances of a folder labelled ‘Correspondence between Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings’ turning up in some obscure archive are extremely small.

Even though I will not be able to answer the questions that I have set, I will continue my investigations in next month’s Forum. In the meantime, you might want to dig a bit deeper and I suggest that you start with 2 books, 2 websites and 1 film.

The books could not be more different. The Hemingses of Monticello by Annette Gordon-Reed (2008) is a detailed and scholarly family history. The World – A Family History by Simon Sebag Montefiore (2022) is considerably longer at 1,304 pages and, to put it mildly, it is significantly more ambitious. In the index, Sally Hemings comes between Helena (mother of Constantine) and Henri II, King of France but in the text she justifies her place.

The two websites are closely related.

www.monticello.org is the website of the Thomas Jefferson Foundation. Go to the section For Educators and click on Research and education and a mass of information will be available to you.

gettingword.monticello.org provides fascinating material from a major African American Oral History Project funded by the Thomas Jefferson Foundation.

The Film is Jefferson in Paris directed by James Ivory (1995). Made before the DNA evidence was taken, it is described as a ‘semi-fictional account’ but it is not implausible.

Roger Mitchell

Contacts

Chair: Alan Potter

alanspotter@hotmail.com

07713 428670

Secretary: Roger Mitchell

rg.mitchell@btinternet.com

01695 423594 (Texts preferred to calls)

Membership Secretary: Rob Firth

suesmembers74@gmail.com

01704 535914

Forum Editor: Chris Nelson

chris@niddart.co.uk

07960 117719

Facebook: facebook.com/groups/southportues

See our archive for previous editions of the SUES Forum!