Introduction

Welcome to Forum 53. In this issue, SUES Chair, Alan Potter, makes an exciting announcement relating to our celebration this year of 150 years of the University Extension Society movement. Please note that Alan’s piece announces revised dates for Peter Firth’s free 4-lecture course on the University Extension Movement, and the SUES AGM.

Also in this issue, Roger Mitchell concludes his intriguing 2-parter on Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings and we have a report on Stephen Lloyd’s recent talk on the Earls of Derby.

It was a pleasure to realise, just before the start of Stephen’s talk, that we needed to put out some extra chairs! We had a record turn-out, reflecting the success of our drive to increase the membership this year and, I assume, the reputation for quality that these Friday afternoon lectures have achieved. Please continue to tell your friends about SUES.

Chris Nelson

Coming up in April 2024

Talk by Alan Crosby

“The great and terrible wilderness, peopled by untutored savages”: Providing Elementary Education in Victorian Lancashire

Friday 26th April at 2:30 pm. All Saints Church Hall, Park Road, Southport, PR9 9JR.

Providing elementary education for the children of Victorian Lancashire was a formidable and challenging task, because of the rapid growth of population, the tremendous pressures of urbanisation and industrialisation, and the weaknesses of the administrative structure. In this county the complexity of religious geography, with a large Catholic population and many different Nonconformist denominations, as well Anglicans, added further to the problem. Nevertheless, as the national political climate moved towards making education compulsory for all, massive expenditure on school provision and the employment of teachers began to transform the picture. This talk looks at who provided the elementary schools, what they taught, and their effectiveness, illustrated with the evidence of personal testimony as well as official reports and the records produced by the schools themselves.

Alan Crosby is a nationally-known local historian, based in Preston. He has been the editor of The Local Historian since 2001 and is the main local history contributor to the BBC Who Do You Think You Are? magazine. He is a very popular tutor and lecturer, and for many years held local history classes in Southport. Alan has published over 40 books on aspects of the local history of North West England, as well as numerous articles. He is currently the chair of the Lancashire Local History Federation.

An Announcement from the Chair:

SUES has been awarded a Heritage Grant from the National Lottery to celebrate our 150th Anniversary!

I am delighted to let all SUES members know that our application to the National Lottery Heritage Grant fund, to support the celebration of our 150-year anniversary, has been successful. As a result, we have secured funding of almost £10,000 to carry out a range of activities to inform people of how the University Extension Society movement came to Southport and Birkdale in 1874 as the University of Cambridge reached out to send lecturers into the community. We will also be able to celebrate the positive impact it has had on so many lives over the years, and promote what we are doing and providing for our learners today.

Under this initiative, we have promised to extend how we inform and enthuse the community about how this unique initiative provided an opportunity for local people to experience university level teaching that they otherwise had not been able to access, either because they were women or poor and uneducated. We will start to do so by revealing the fascinating heritage from our recently uncovered archive, which will be outlined through a series of four free lectures by Peter Firth on 16th, 23rd and 30th September and 7th October entitled The University Extension Movement.

An exhibition, bringing to life the struggle to have access to education and learning, will be held this year at The Atkinson from 27th July to 24th August and will again be free to all. It will highlight individual people, and women in particular, whose work in helping others to learn was outstanding at the time and still resonates today. This exhibition will be launched when Stephen Whittle, The Atkinson’s Principal Manager, speaks at our AGM on Wednesday 24th July (a revised date from that originally published).

This funding will also enable us to go into parts of the community we have not accessed before, to remove any barriers to participation in SUES that may exist. As members, you will have a great part to play in this. We will also be able extend our reach through social media, drawing in people more used to being informed in such ways.

As the year rolls on, further events and a free booklet will showcase the altruistic work of local people in the past, and volunteers today, to ensure increasing numbers of people gain the benefits from learning through SUES and therefore live better lives as a result. Southport has much to be proud of with SUES, especially as it is the last remaining such society in the UK. This 150-year anniversary provides an ideal opportunity to expand our offer, include more groups represented in society and celebrate our unique and valuable heritage. I am sure you are as pleased as I am that our Society has been recognised by this grant from the National Lottery, and all of us in SUES can now look forward to an even more exciting year ahead!

Alan Potter

Meeting Report:

Shakespeare, the Earls of Derby and the North West with Stephen Lloyd, 22 March 2024

We had one of our largest audiences ever for this talk, perhaps reflecting our increasing membership as well as the popularity of the subject matter. Mary Ormsby introduced our speaker, Dr Stephen Lloyd, who has been Curator of the Derby Collection at Knowsley Hall near Prescot since 2012 and has an extraordinarily detailed knowledge of the Earls of Derby (the Stanleys) and their achievements and passions, including an early enthusiasm and support for theatre.

Stephen explained that the title has no connection with the city of Derby, or the county of Derbyshire, but refers to the West Derby Hundred in historic Lancashire. In addition to their current family seat at Knowsley Hall near Prescot, the Stanleys had many other houses, including Crag Hall in Cheshire, Lathom House near Ormskirk, and several houses in London, such as Derby Gate (on the site of the present Portcullis House). They had many estates throughout the north of England, and also in Warwickshire, Kent, Berkshire, Surrey and London. They also ruled the Isle of Man between 1404 and 1736!

We heard how the Stanleys had a way of always being on “the right side”, for example, making a timely switch from supporting Richard II to Henry IV; they also married well on many occasions. Thomas, the 2nd Lord Stanley (1403-1504) was tasked by Henry VII to “keep an eye on” Lady Margaret Beaufort – the country’s richest woman and Henry’s mother. He married her! Thomas was created the 1st Earl of Derby by the king after the Battle of Bosworth Field, which brough him great wealth and influence at Court; indeed, Lathom House and Knowsley Hall became known as the ‘Northern Court’. After the reformation, the Stanleys kept order on behalf of the Crown in the north of England, where there were some powerful Catholic families.

Henry, the 4th Earl (1531-93), was associated with a performing company called Derby’s Men and, during his time, a number of leading acting companies performed at Knowsley and Lathom. However, it was his son Ferdinando (c1559-94) who is particularly associated with the early theatre. As Lord Strange (another family title) Ferdinando was patron of a company called Lord Strange’s Men and the young William Shakespeare also benefited from his patronage when writing his earliest plays. Less than a year after becoming the 5th Earl, Ferdinando was murdered by poisoning. Six of the leading actors of the day (including Will Kemp, who was probably a member of the 4th Earl’s household) then formed The Lord Chamberlain’s Men, changing their name to The King’s Men after the death of Elizabeth I. Shakespeare wrote many of his best-known plays for these actors, having first worked with them when they were all members of the 5th Earl’s company of players.

Ferdinando arranged for a playhouse to be built in Prescot. This operated for about 20 years and is thought to have been the only purpose-built theatre outside London at the time. It would have been used by touring theatre companies visiting Knowsley. (If you were wondering why the Shakespeare North Playhouse, which opened in 2022, is in Prescot, well now you know!)

William, the 6th Earl (c1561-1642), was also a great patron of the theatre and his acting company, Paul’s Children, was a favourite of Elizabeth I.

James, the 7th Earl fought for Charles I in the Civil War; he was arrested, and beheaded in Bolton. He is known as The Martyr Earl. While he was away fighting, his wife, Charlotte, famously led the defence of Lathom House against Cromwell’s forces. Following the Civil War, the family lost much of their land, although about half was returned by Charles II; it took about 150 years to regain the estates, and the late 17th and early 18th centuries were a time of rebuilding.

James, the 10th Earl (1664-1736), built a great art collection, including the family portraits which hang in the dining room at Knowsley.

Horse racing has been a passion of the family since Ferdinando’s time, but it was the 12th Earl, Edward (1752-1834), who established The Oaks (named after his Epsom residence) and The Derby. The 13th Earl was involved in the founding of the Grand National and the 16th and 17th Earls established a stud at Newmarket which continues to this day.

Edward, the 12th Earl (1752-1834), had a passion for natural history, as did his son the 13th Earl, also Edward (1775-1851), who was an early President of the Zoological Society. Knowsley had an aviary and a menagerie at this time (the present-day Safari Park can be considered to be a revival of this tradition). The poet and artist Edward Lear lived and worked at Knowsley from 1831 to 1837, where he painted watercolours of the birds and animals; he also wrote his Book of Nonsense to entertain the 13th Earl’s grandchildren. Lear later wished to undertake a tour of Europe and Asia, to develop a career as a landscape artist, and the 13th Earl sponsored his long trip (around 10 years) and continued to buy Lear’s paintings.

Stephen introduced us to a few more Earls of Derby: the 14th Earl, Edward Geoffrey (1799-1869), was three times Prime Minister and mentor to Disraeli. His 1867 Reform Bill increased suffrage and he visited the USA where he was affected by slavery and poverty among Irish immigrants. The 15th Earl, Edward Henry (1826-93), was Foreign Secretary. His younger brother Frederick Arthur, the 16th Earl (1841-1908), was Governor General of Canada; he presented Canada’s Stanley Cup for ice hockey and Vancouver’s Stanley Park is named after him.

Stephen also told us a little about his own work. He has been researching the Stanley family’s history, working with Lady Derby (a former curator at Buckingham Palace). He explained that the archives are now split between Knowsley (family papers), the Lancashire Records at Preston (papers concerned with land) and Liverpool City Archives (political papers given in lieu of death duties). During the Covid period the Lear watercolours at Knowsley were all digitised and are now available to view online. About 50% of the work involves managing the conservation of items in the Derby collection; 2 or 3 paintings per year are conserved at Liverpool’s National Conservation Centre and there is also conservation work on books, textiles, furniture, silver, etc.

Stephen spoke without notes and without any visual aids, instead handing out copies of the Knowsley Hall guide book and referring us to various images in the book to illustrate his talk. (We were invited buy the book afterwards, and my copy has been very useful in preparing this report.)

Alan Potter closed the meeting, thanking Stephen for his talk, and commenting on his obvious extensive knowledge and passion for his subject, and on his amazing memory for detail.

Chris Nelson

Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings – Part 2

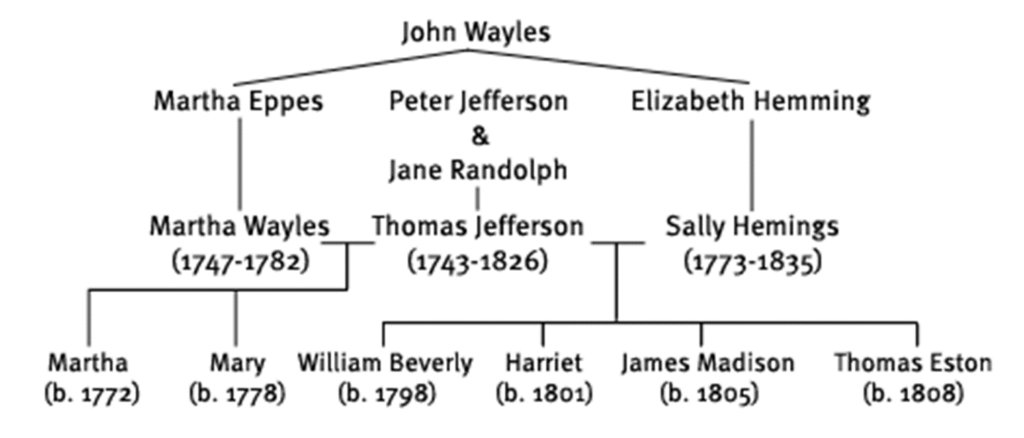

In this concluding instalment, I want to try to make Sally a real individual rather than a stereotypical slave. A helpful start would be to make some use of the term ‘enslaved person’ rather than always calling her a ‘slave’. Some might consider that ‘enslaved person’ is a woke term that is part of wider culture wars, but it does remind us that at her core she is a person and that enslavement is her current condition rather than the essence of her being. It would also be useful to take care when describing her ethnicity. Three of her four grandparents were white and one of them was born in Lancashire. She was half-sister to Jefferson’s wife and so she was lady’s maid to her own niece. Things are now getting complicated and so we need a family tree.

The story starts with an enslaved African woman whose name is unknown to us. She had six children with an English sea captain named John Hemings. One of these children was Elizabeth (or Betty) Hemming (or Hemings). She was born into slavery in 1735 and died a slave in 1807. She was owned by John Wayles and he was the father of six of her twelve children. John Wayles was a self-made man. Born in 1715 in modest circumstances in Lancaster, England, he went to Virginia as an indentured servant and became a lawyer, planter and slave trader. In 1746 he married Martha Eppes. In 1748 she gave birth to a daughter also called Martha. The child survived, but the mother died within days of the birth. Wayles subsequently remarried, and had more legitimate children, but by 1761 both his second and his third wives had died and he had subsequently begun a relationship with Elizabeth Hemings, who had come into his possession as part of the Eppes marriage settlement of 1746. She already had four children with an unknown black man as father and she had another six with Wayles before his death in 1773. The youngest of these was Sally Hemings. When Wayles died, the Hemings family seem to have moved to Monticello because they were inherited by Wayles’ daughter, Martha who was married to Thomas Jefferson. At Monticello, Elizabeth completed her family with another two children born in 1776 and 1777. Their father was Joseph Neilson, a white man employed as Jefferson’s chief carpenter.

The Monticello website provides the following summary of Elizabeth Hemings’ life and importance.

“Elizabeth (Betty) Hemings (1735-1807) was the matriarch of a prominent and extensive family that made up a third of the population at Monticello, the largest family to ever call Monticello home. Ties of bondage and kinship forever intertwined the Hemings and Jefferson families, demonstrating the complex nature of relationships between enslaved people and their owners. Elizabeth Hemings’s children and descendants occupied the most important household and trades positions on the mountain, and many of her children were allowed to hire themselves out and keep their earnings, an uncommon experience among those enslaved by Thomas Jefferson. Three of her children and six of her grandchildren were the only people Thomas Jefferson freed. Her daughter, Sally Hemings, became one of the most well-known enslaved women in American history due to Jefferson’s paternity of her children, a connection that inspires continued evaluation and exemplifies the complexity of race and slavery in America.”

An example of this intertwining is the fact that John Wayles was the father of Thomas Jefferson’s wife, Martha Wayles and also of Sally Hemings, his concubine. Martha Wayles married Thomas Jefferson in 1772 after the death of her first husband. They had six children but four of them died in infancy. Two daughters survived to adulthood, but Mary, the younger of the two, died at the age of 26. She had married a first cousin and had three children. The elder daughter, Martha, had twelve children and outlived her father, inheriting his estate, his slaves and his debts. Despite the loss of four young children, and his wife’s deteriorating health, the marriage of Thomas and Martha was a happy one and he was devastated by her death in 1782 at the age of 33. On her deathbed she had asked him to promise not to marry again. He made that promise and kept it. Whether that explains or excuses his relationship with Sally Hemings is an open question.

That relationship probably began in Paris six years later. Jefferson was appointed American ambassador to France in 1784 and took his elder daughter with him. Three years later he sent for his younger daughter, Mary (known as Polly). She was only ten years old and it was intended that she should travel with her black nurse. However, the nurse became ill and seems to have been replaced at short notice by Sally Hemings who was probably only five years older than her charge.

Travelling via London, the girls reached Paris safely and Sally became part of the household, which also included her elder brother, James, who was Jefferson’s cook. It seems likely that Sally’s relationship with Jefferson began during this period in Paris, and perhaps such a relationship was more likely to develop in Paris than in Virginia. Living in a town house, and acting as lady’s maid to Jefferson’s daughters, Sally would be in closer contact with the family than would be the case at Monticello and may even have been involved in social events. We know, for example, that new gowns were provided for her. Her status in France was uncertain because slavery itself was not officially recognised. When Jefferson and his household left Paris in September 1789, the French Revolution was under way and freedom was in the air. However, there is no evidence that Sally sought to remain in France rather than return to Virginia where her legal status as a slave would be impossible to challenge. There are later family stories that she made an arrangement with Jefferson that, on his death, she and any children would gain their freedom. This is what happened when Jefferson eventually died at the age of 83, but we do not know whether a pledge had been made more than 35 years earlier.

Back in Virginia, Sally became part of the Monticello household. Her mother, Elizabeth, continued to be a matriarchal figure in that household until her death in 1807. Sally’s relationship with Jefferson also continued. She may have had her first child, possibly a stillbirth or perinatal death, as early as 1790 but she certainly had six children between 1795 and 1808. This was the period when Thomas Jefferson was Vice President (1797-1801) and then President (1801-1809) and so most of his time was spent in Washington.

However, whenever possible, he returned to Monticello and the dates of conception fit with his presence there. Three daughters were born but only one reached adulthood. However, all three sons survived. They were all trained at Monticello as carpenters. Beverly and his sister Harriet were both allowed to leave Monticello in 1822. Like their brothers, they both had light skin and seem to have lived in white society but little is known about what happened to either of them. We know rather more about the two younger sons, Madison and Eston. They were released in Jefferson’s will, probably at the same time as their mother was informally freed by Jefferson’s legitimate daughter. All three are listed as free white (sic) people in the 1830 census, although in another census 3 years later, Sally describes herself as a free mulatto (mixed race) who had lived in Charlottesville since 1826. She died there in 1835.

In the late 1830s Madison moved to southern Ohio where he worked as a carpenter and owned a farm. He chose to live in the black community and died in 1878. Earlier in the 1870s he had answered questions about his early life, and about his parents, and these were published in an Ohio newspaper. Eston, the youngest son, also moved to Ohio with his wife and children. He combined carpentry with music and, like his brothers and indeed his father, he played the fiddle. He became well known as a professional musician and, in 1852, he moved to Wisconsin where he changed his surname from Hemings to Jefferson and his racial identity from black to white. He died in 1856 but he had male descendants, one of whom was able to provide DNA that was used for the testing that confirmed that Thomas Jefferson was his ancestor.

I have tried to give the known facts and to avoid either speculation or judgement, but at the end of this article, I feel that a few comments are appropriate.

Do these revelations affect our view of Jefferson? Obviously, they must have some impact, but I think only a limited one. We already know that there were many sides to Jefferson. He might appear as the enlightenment philosopher, dispensing wisdom particularly through his correspondence with the great and the good both in America and in Europe. At other times, he might be the practical politician, helping to create a new nation, extending its territory with that boldest of real estate deals, the Louisiana Purchase, but fearing that the unresolved problems around the issue of slavery might lead to the destruction of the United States.

However, at all times, he remained a Virginia Planter, born into a privileged class, educated at the College of William and Mary, connected by marriage to many of the Virginia elite and enjoying a lifestyle that was made possible by slavery.

The knowledge that, as well as a legitimate family, he had what was called a shadow family, is not totally unexpected. Many of his contemporaries, including his father-in-law, had similar arrangements. Jefferson was a widower, who had promised his wife that he would never remarry. His relationship with Sally Hemings was long lasting and unique. There have been no allegations that Jefferson had sexual relationships with other members of his household. No cruelty or neglect has been suggested. Sally and her children remained at Monticello until Jefferson’s death and were then freed by his legitimate daughter, with whom they appear to have been on good terms. Secrecy and, on occasion, denial are justified criticisms, but it is hardly surprising that Jefferson did not expose what he would regard as family matters to public gaze. If they had become public knowledge at the time, would this have jeopardised his public career? It is hard to know, but perhaps worth noting that the 1790s saw the first sex scandal in American political history involving Alexander Hamilton and his affair with a married woman. Hamilton was Jefferson’s political enemy and Jefferson played a role that was at best unhelpful and at worst unscrupulous.

Do these revelations affect our view of slavery? The evils of the institution itself, and of its particular manifestations in the American south, are self-evident but the story is a complicated one and research into families like the Hemings’ shows that the experiences of enslaved people varied greatly. Sally and her mother, Elizabeth, certainly had influence, and perhaps power, at Monticello and the same was true in many other places and situations. Enslaved women were central to the development of family life in a society where slave marriage had no legal status and where family groups could be split up by sale or exchange. This was not common practice at Monticello during Jefferson’s lifetime, but at his death he left huge debts of more than $100,000 and, apart from the Hemings family, most of his slaves were sold.

On the whole, Jefferson treated his slaves relatively well, although his frequent absences on official business meant that his overlookers were often in day-to-day control and made more use of punishments. Even so, Jefferson’s slaves at Monticello probably fared better than Washington’s slaves at Mount Vernon. Washington was as much a disciplinarian with his slaves as he had been with his troops, and those who tried to escape or desert were hunted down.

Research into the Hemings family has also shown the dangers of the casual assumption that all blacks were slaves and that all slaves were black. There were significant numbers of free blacks throughout the United States, including more than 30,000 in Virginia, by 1810. Both slaves and free blacks would often be of mixed heritage. Sally Hemings had three white grandparents and, after gaining their freedom, some of her children became part of white communities.

Finally, it may be worth giving some credit to Jefferson for his part in ensuring the passage of An Act to prohibit the importation of slaves into any port or place within the jurisdiction of the United States. As part of the compromises to get approval for the constitution, it had been specified that Congress was not allowed to ban the Slave Trade until 20 years had elapsed. In his State of the Union Address in 1806, President Jefferson reminded Congress that this 20-year period was now at an end and he encouraged them to take action. Perhaps rather surprisingly, this was a much less contentious issue in America than it was in Britain. Congress passed the Bill and, on 2nd March 1807, Jefferson signed it into law. Three weeks later, and on the other side of the Atlantic, George III signed the equivalent British legislation which made the slave trade illegal from 1st May 1807. This was 8 months before the American legislation came into effect on 1st January 1808. Jefferson was still President at that date, and ending the importation of slaves should count as one of his achievements. Perhaps he hoped that this would lead to the ending of slavery itself, but the internal trading in slaves continued and, by the time of his death in 1826, it was clear that the number of slaves in the south was continuing to grow. The 1830 census shows that the total number of slaves was approaching 2,000,000 and the more children born to slave mothers, the happier and more prosperous slave owners and traders would be.

Jefferson died on 4th July 1826, 50 years to the day after the publication of the Declaration of Independence which he had drafted. Perhaps the greatest of his many skills was the ability to write clearly, quickly, and memorably. He retained that skill into old age and it is appropriate to let Jefferson have the last word with two extracts from letters that he wrote to friends in 1820, reflecting on his failure to solve the problem of slavery. In a much-quoted comment, he wrote that “this momentous question, like a firebell in the night, awakened and filled me with terror. I considered it at once as the knell of the union”. In an even more vivid image, he wrote that maintaining slavery was like “holding a wolf by the ear and we can neither hold him nor safely let him go”. As so often, Jefferson, the polymath, had got to the heart of the problem, but even he was unable to find a solution.

Roger Mitchell

Contacts

Chair: Alan Potter

alanspotter@hotmail.com

07713 428670

Secretary: Roger Mitchell

rg.mitchell@btinternet.com

01695 423594 (Texts preferred to calls)

Membership Secretary: Rob Firth

suesmembers74@gmail.com

01704 535914

Forum Editor: Chris Nelson

chris@niddart.co.uk

07960 117719

Facebook: facebook.com/groups/southportues

See our archive for previous editions of the SUES Forum!