Introduction

Welcome to Forum 51. Mary Ormsby is our star contributor this month, with a report on Robert Eden’s recent talk and, in the 150th anniversary year of the founding of the University Extension Movement in Southport, an article about the town in 1874. Thanks to Mary for her hard work this month. There’s also a short piece from me about fig wasps (a subject on which I was entirely ignorant until a few weeks ago).

May I remind you that we welcome contributions to Forum from SUES members. My contact details are on page 13.

Chris Nelson

Coming up in February 2024

Talk by Julia Clayton

The Fiction of Forgery: Art and Authenticity in the English Novel

Friday 23rd February at 2:30 pm. All Saints Church Hall, Park Road, Southport, PR9 9JR.

Julia Clayton was Head of Classics at King George V College, Southport, from 1996 to 2019. In 2019 she completed an MA in Creative Writing at Edge Hill University and has subsequently had several short stories published. She is currently working on a PhD at Edge Hill on Invented Artworks in Fiction. Julia’s blog on the afterlife of Greek art (including a piece on Southport Monument) can be found at https://classicalclayton.blogspot.com

This talk will explore the presentation of art forgery in fiction, including the reasons why fictional characters commit forgery: for financial gain; to expose the superficiality of the art world; as a medium of exchange; to cover up a murder and even to prove the truth of a literary theory. By looking at fictional art forgers alongside real art forgers, including Han van Meegeren and Shaun Greenhalgh, we shall explore the way in which forgers often succeed by exploiting gaps in art history, or by creating ‘lost’ works which meet the expectations (and dreams) of art historians.

Novels featuring forged artworks also often raise questions about the link between personal and artistic authenticity, as characters who engage in or facilitate art forgery are often not who they appear to be. Julia will be arguing that fiction about art forgery makes an important contribution to some of the questions posed by art historians. Can forgery ever be morally justified? Do we over-value the idea of ‘authenticity’, especially in the art market? Can a forgery have the same aesthetic value as a genuine painting? Is it possible to derive the same amount of pleasure from a forgery as from a genuine artwork?

2024 Courses

The next SUES course will be Alan Potter’s Technology – Understanding Just How Things Work! which starts on 8th April. As usual, you can enrol by contacting Rob Firth by email at suesmembers74@gmail.com. The preferred payment method is bank transfer; alternatively, you can send a cheque to Rob.

Peter Firth’s course on the University Extension Movement, which was to have commenced on 13th May, has been rescheduled and will now take place during September and October, launching the SUES programme for 2024-25. This four-session course is part of our 150th anniversary celebrations and will be free to attend. The revised dates for Peter’s course will be announced in due course. Meanwhile, if you have the original dates in your diary (13th & 20th May; 3rd & 10th June), you are now free to make other arrangements for those days!

Meeting Report:

From Stinky Ponds to Cracked North Sea Pipelines

by Robert Eden, 26 January 2024

On 26th January we had our first SUES talk of 2024, and what a talk – it got the new year off with a bang, or perhaps more accurately, a bad smell!

Professor Robert Eden, formerly of UMIST and founder of Rawwater, was introduced to us by Roger who had first met him half a century ago when Robert was a sixth former at Hinchingbrooke school in Huntingdon. He had been taught biology by Glendon and they both remembered him as an enthusiastic, optimistic boy with unbounded curiosity across a wide range of interests – perfect qualities for the inventor and entrepreneur he was to become.

Robert’s talk centred around Sulphate Reducing Bacteria (SRBs) and their role in the corrosion of pipes, particularly in the oil industry. These bacteria have been around for some three and a half billion years, and whilst we now understand the size of this biome we do not understand its complexity.

The SRBs are usually inactive in open water sources, but are able to survive very high pressures (up to 10,000 psi) and temperatures over 100oC. At around 5 microns, they cannot be removed by filtration and, in the right conditions, through anaerobic respiration, they reduce ‘sulphates’ and produce hydrogen sulphide, a process which can operate even at low temperatures.

Sulphate occurs widely in seawater, sediment, and water rich in decaying organic material. It is also found in more extreme environments such as hydrothermal vents and oil fields. The hydrogen sulphide (H2S) produced has the smell of rotten eggs and is almost as toxic as hydrogen cyanide, causing loss of consciousness at levels >700 ppm. Luckily, the smell is detectable at 0.01 to 1.5 ppm and, over the years, detectors have been developed which give an audible alarm when H2S is present.

Robert gave a couple of examples of the potency of H2S – fish and frogs being suffocated by the gas being produced under a sheet of ice on a pond and industrial accidents where exposure has led to loss of consciousness. A few brave ones in the audience even had a smell of his vial of H2S (!), which he also used to demonstrate the effectiveness of the detectors.

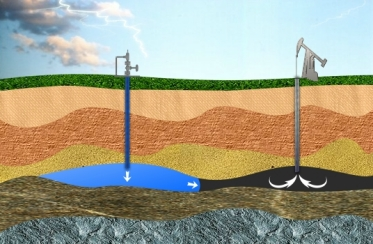

Sea water is often injected into a well in order to extract the oil. This water contains a high concentration of sulphates and introduces bacteria into the system which eventually leads to ‘biological souring’.

Biological souring requires: SRBs, water, sulphate, oxygen-free conditions and an organic food source, so oil reservoirs are a perfect home for them!

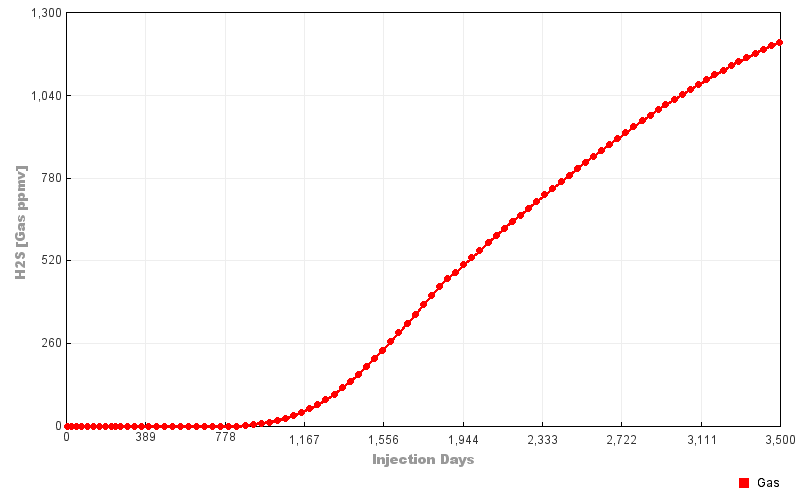

Initially North Sea reservoirs did not contain any hydrogen sulphide, but the levels rose about 3 years after injection.

So what is the problem you may ask. The souring causes the metal of the pipeline to become brittle and crack. Since these pipes typically work at a pressure of 5000 psi, these cracks can propagate down the pipe for many hundreds of metres and cause an environmental disaster. Today such events are rare because steels resistant to hydrogen sulphide have been developed as have methods of controlling souring itself.

For example, adding nitrates to the water can reduce souring, since the SRBs react preferentially with the nitrate to produce nitrogen; however, once all the nitrate has been consumed, the SRBs react with the sulphates even more rapidly since the biomass has been ‘fed’ with the nitrates.

Whilst chemical souring is a feature of oil reservoirs, the impact of SRBs can be felt and seen closer to home, on Southport Pier. The sand, sea water and effluent contamination have combined to corrode the metal legs of the pier, so it would seem the pier is doomed.

Robert’s talk was accompanied not just by images but by exhibits and examples and it was presented with characteristic enthusiasm and optimism. A lively question and answer session followed and new problems and possible solutions were still being raised as refreshments were served.

Mary Ormsby

Can Vegetarians Eat Figs?

Siobhan and I have recently returned from a trip to southern India. We had a wonderful time, even though it meant missing three sessions of Roger’s course on Colonial America!

We finished our tour with three nights at a beach resort on the coast of Kerala. This hotel had extensive grounds, including a butterfly garden, and employed three naturalists who were available every day to help us discover and understand the local wildlife.

We were amazed to find that several owls lived in the trees in the hotel grounds, and these experts knew exactly which way to point their telescope (and our binoculars and cameras) to find them during the day.

The naturalists also ran a daily session called Beneath the Leaves, in which they used a projecting microscope to show us some of the smaller plants and creatures. It was during one such session that we learned about the extraordinary symbiotic relationship between figs and wasps.

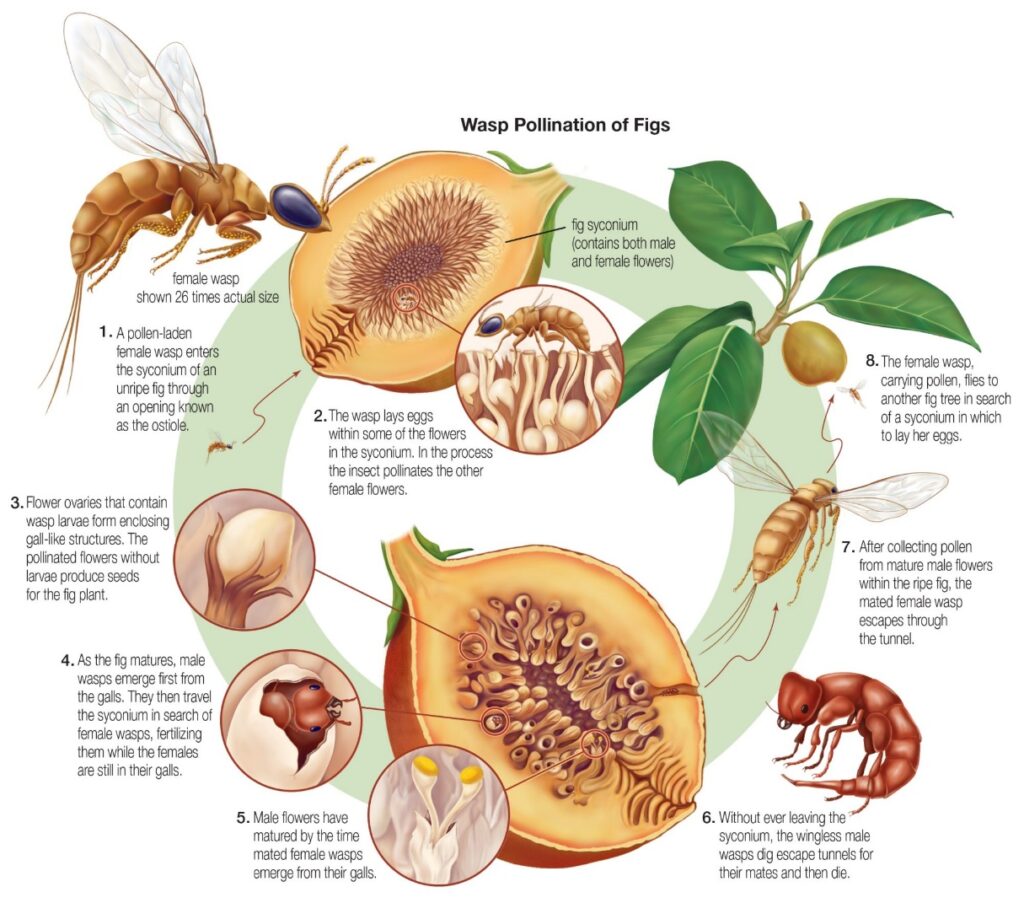

The fig is an unusual fruit; the flowers are on the inside, so pollination (necessary if the fig is to ripen) is a challenge. Nature’s solution is the fig wasp. For every species of fig (and there are about 750 of them on the planet) there is at least one dedicated species of fig wasp. These wasps are tiny, typically 1-2 mm in length. A female wasp will enter the fig through a narrow passage at the end, called the ostiole; this is usually a one-way journey, as she will typically lose her wings and antennae during her journey to the centre of the fig.

If the female wasp enters a male (inedible) fig, she lays her eggs before she dies. Some of her offspring will be male wasps, which have no wings or antennae and will never leave the fig. They impregnate the young females (often their sisters!) before they hatch and will then burrow through the fig, creating escape routes for the females, before they die. The young females then leave the fig, and search for another male fig in which to lay their own eggs and continue the cycle.

Edible figs are ‘female’. If a wasp enters a female fig, her eggs will not be viable, and she will die with no offspring; however, she carries pollen from the (male) fig in which she was hatched, and this is transferred to the flower, resulting in pollination of the fruit, which then swells and ripens. A video produced by the Natural History Museum provides a useful explanation of the process1.

Image: Encyclopaedia Britannica/Getty Images

So, every fig we eat apparently contains the remains of at least one dead wasp. Our Indian naturalist friends showed us evidence for this under the microscope. Our little group of British tourists then proceeded to discuss the obvious question: assuming that the idea of the dead wasp doesn’t take their appetite away, is it acceptable for a vegetarian (or vegan) to eat a fig? We tied ourselves up in philosophical knots, but I have since looked for published opinions on the subject.

As explained by Pino2, edible (female) figs contain an enzyme which breaks down the body of the dead wasp, absorbing the protein into the flesh of the ripening fruit, so by the time the fruit is eaten, there is no trace of the wasp. The crunch when you eat a fig comes from the seeds and not from a wasp’s exoskeleton! My enquiries have also revealed that many commercially grown figs are now seedless ‘parthenocarpic’ varieties which, due to a mutation, can produce ripe edible fruit without pollination; see, for example, the video by Ragusea3.

Ragusea also says that pollinated figs are considered to be acceptable vegan food because, even though an animal has died in the production of the fruit, the process is “totally natural – it’s what the wasp wants to do”. This does appear to be a view commonly expressed in discussions on plant-based diets4,5. One British vegan website5 observes that, since the dead wasp is broken down and absorbed within the fig, “you are not really eating the wasp, any more than a meat-eater is eating grass when they consume beef.”

Sources:

1Natural history Museum video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EbmrQENfhhM

2Article by Melissa Pino: https://www.planetnatural.com/fig-wasp/

3Adam Ragusea video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tRBiY65N2gk

4https://plantbasednews.org/lifestyle/food/are-figs-vegan/

5https://www.veganfriendly.org.uk/is-it-vegan/figs/

Chris Nelson

Southport in 1874

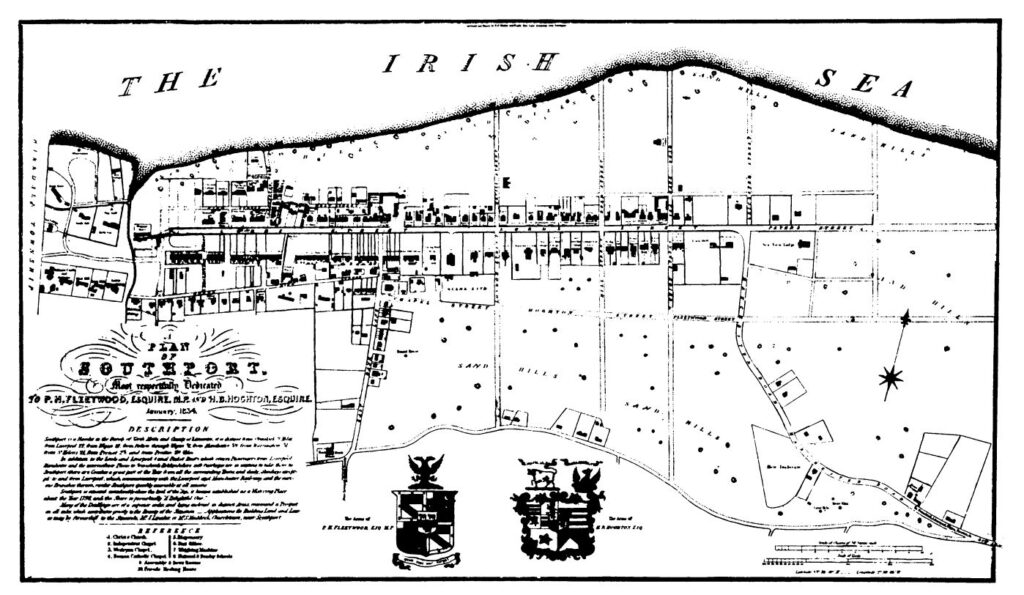

In preparation for Peter Firth’s course later this year, which will cover the history of the University Extension Movement in Southport in this, its 150th anniversary year, I thought it might be interesting to explore what Southport was like at this time.

In the 1872-83 Directory for the town1, Southport describes itself as “one of the most popular watering-places in the kingdom… Its delightful sea-girt position, and the extreme salubrity of its climate, have produced an unparalleled change, transforming it in a few years from a small almost unknown village of fisherman’s huts into an extensive and prosperous town, chiefly composed of villa residences of elegant structures so that it has been styled, with great appropriateness, ‘The Montpellier of the North’.”

Since its beginnings as Meols, or North Meols, Southport’s local government has passed through various stages; from a rural area administered by “a mix of manor court, parish vestry and magistrate’s bench”, followed in 1846 by an elected Board of Improvement Commissioners who carried out schemes of gas lighting, paving and sewerage, before finally becoming a borough in 1867 when the population was around 15,0002.

The town was built on the land of two local landowners, Charles Hesketh MA, rector of the parish, and the Trustees of Charles Scarisbrick of Scarisbrick Hall. Thomas Part and W H Talbot, who managed the development for the Scarisbrick Trustees, ensured strict regulations were applied in terms of the type and spacing of houses which “contributed in no small degree to the elegant appearance of the town.”

Development

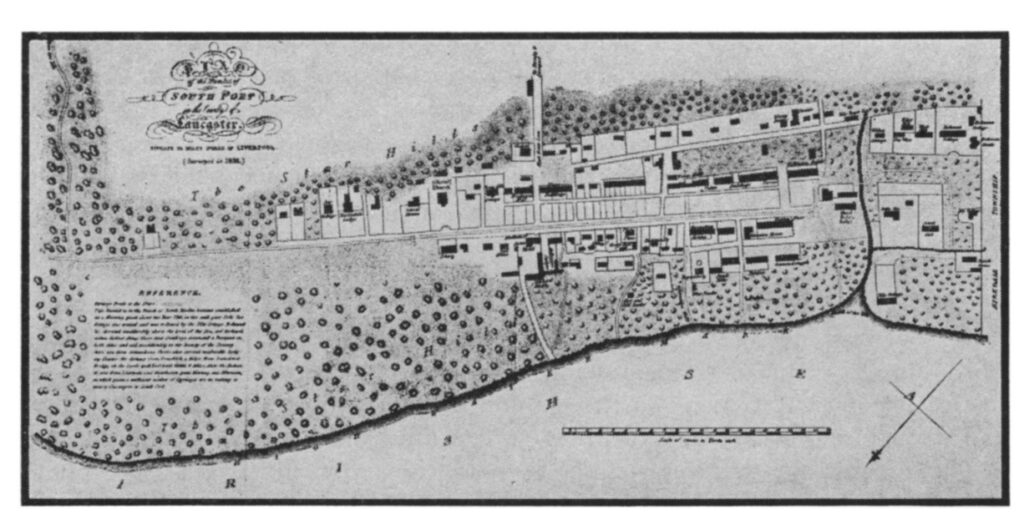

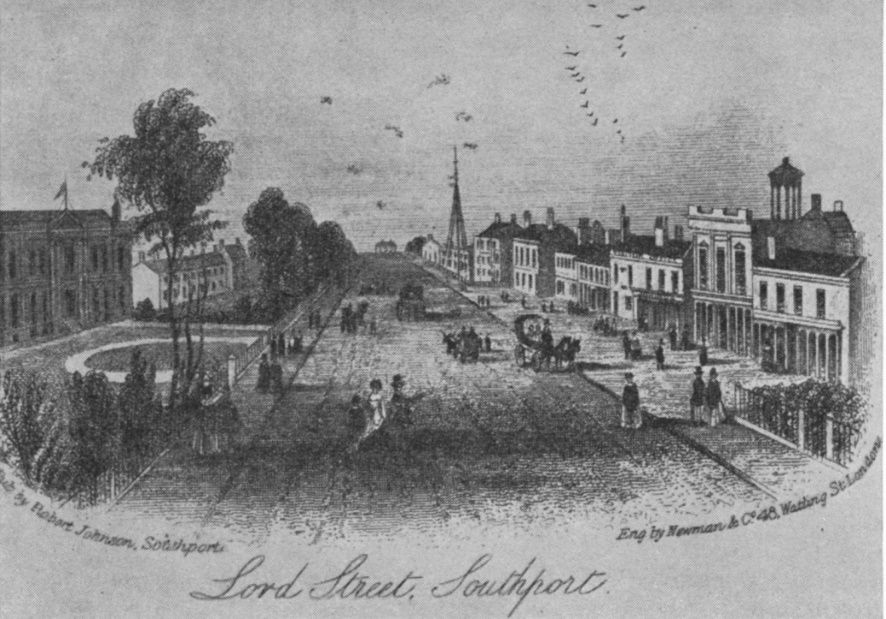

Lord Street, or more correctly Lords Street, acknowledging both the Scarisbrick and Hesketh origins of the town, was the focus for the town’s development which is well illustrated by two plans from 1824 and 1834 respectively.

The west side, in time, developed into the shop side, while the east side became the garden side.

Lord Street

Analysis of the listings in the 1872 directory shows the difference in the west and east sides of this main thoroughfare. Both have around 20 residents whose occupation isn’t given. The west side has 20 buildings listed as “apartments” while the East has 35, but the main difference is in the number of “businesses or occupations listed”; 117 for the West side compared to 34 for the East. The total number of drapers, tailors, dressmakers and milliners at twenty-eight, was four times greater than the next most popular occupation – surgeon, doctor or dentist. They were obviously a well-dressed lot! Unusual occupations include “perambulator manufacturer” and “Registrar of servants”, but in the Directory proper the most common listing is for “Lodging House Keeper”!

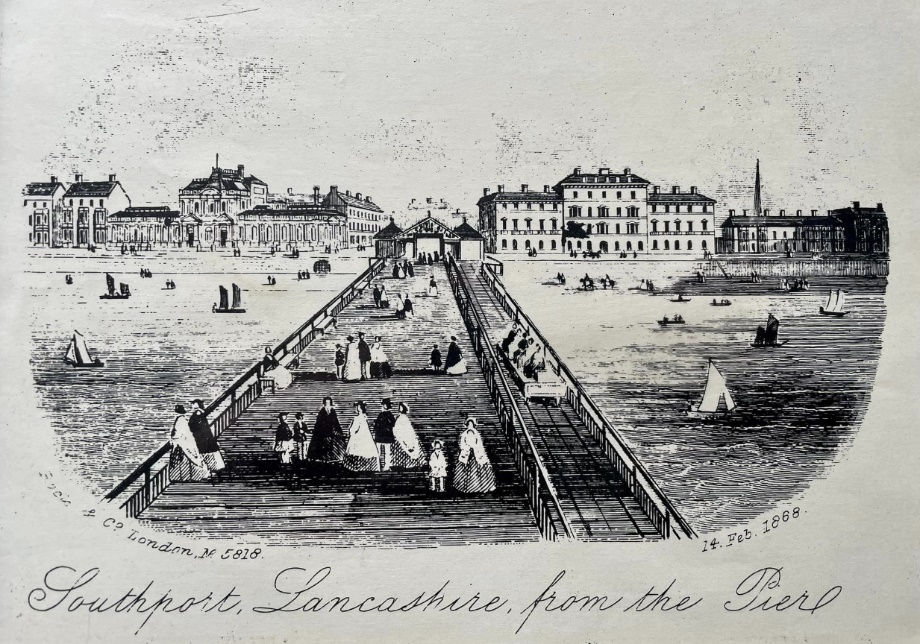

The Promenade came into being in 1835, as a method of preventing the ingress of storm blown sand which was threatening to overwhelm the properties on the seaward side of Lord Street. The town’s pier was first built in 1860 but the Marine Lakes would not be created until 1887 and 1892.

Public Buildings

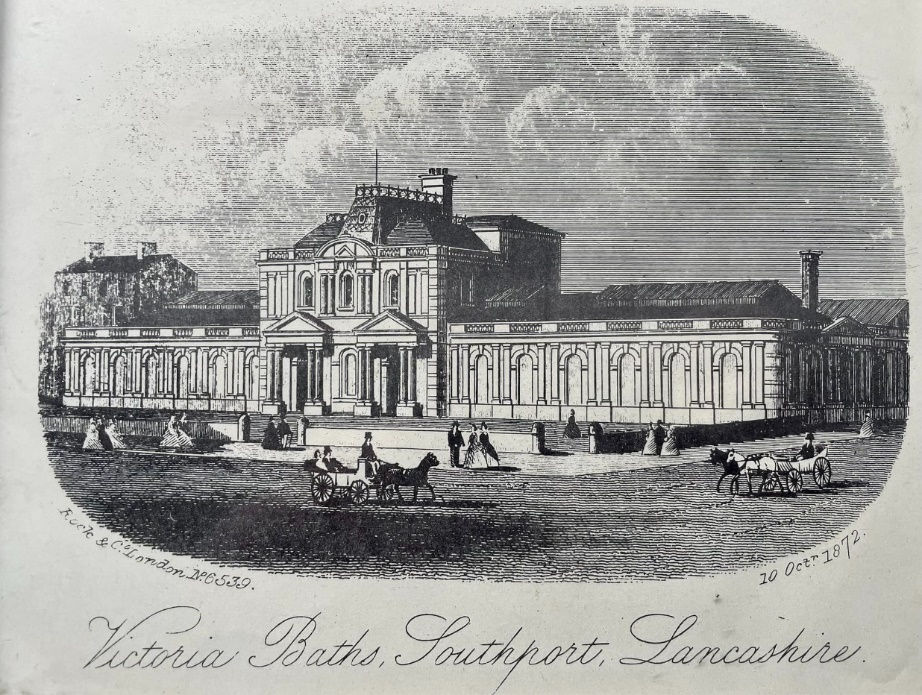

In 1874 the young town boasted few public buildings, but several were planned. The Town Hall had been built in 1853 at a cost of £4500. In 1872 it consisted of “on the upper floor a large assembly room – for public meetings, concerts and entertainments, capable of accommodating 600 persons – the council chamber, ante room and offices; on the central floor are the mayor’s parlour, rooms for the borough officials, town clerk, accountants, collectors &c with a large committee room; and on the other side of the entrance are the court of petty sessions and magistrates room, while on the basement are the police inspector’s office, cells”1.

The Victoria Baths on the Promenade had been opened on 5th June 1871, while the foundation stone for Cambridge Hall had been laid on 9th October 1872 and plans were in hand to build a Pavilion and Winter Gardens on the west side of Lord Street.

Transport Links

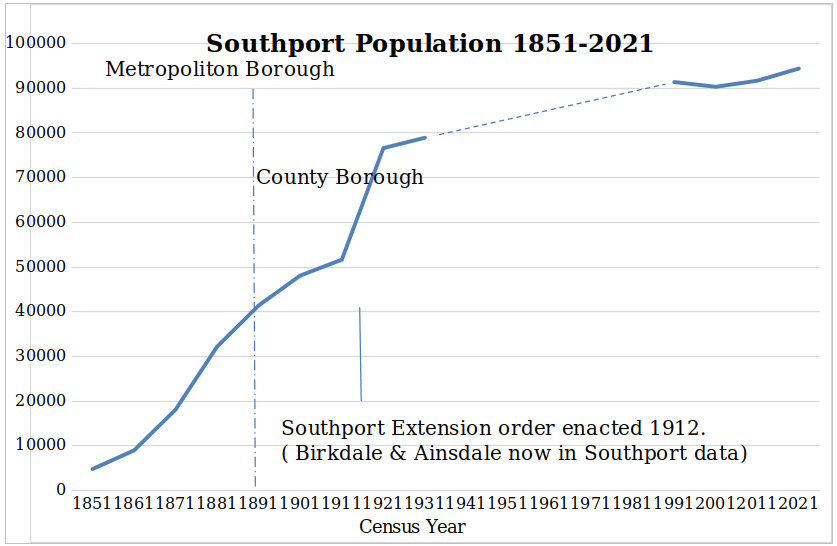

The population was growing rapidly, as shown by the graph below, with the 1871 census listing some 18,000 people living in the Municipal Borough, which did not include Birkdale or North Meols.

The arrival of the railways transformed Southport. The line to Liverpool begun in 1848 was completed in 1850 and the line to Manchester followed in 1855. Southport now became home to many who worked in Manchester or Liverpool but chose to live in Southport.

The railways also meant that workers from the industrial towns of Lancashire and Yorkshire could easily visit the town on their annual holidays. The result was described in the local newspaper: “Never before within memory has the town witnessed so busy and bustling a scene as its streets presented during Whitweek. The railways from the manufacturing districts poured in their thousands daily, who flowed through the streets in one vast living stream, and swarmed on the wide expanse of shore like a newly disturbed ant hill”2.

Schools

The directory states there are four public day schools, in addition the listings show forty-two ‘Boarding or Day schools’, located in the area between Aughton Road to the north and Alexandra Road to the south and between the coast and Hampton Road. The largest density of twenty-one schools being in what we would call the town centre, from the sea front to Wright Street and between Leicester Street and Portland Street. The number of small private schools in Southport was to contribute to the success of the University Extension movement, whose lectures were often attended by the older pupils.

Societies

Among the societies listed in the Directory is the Literary & Philosophical Society, listed at 149 Lord Street and in the Lord Street Chamber. The chairman, Robert Craven Esq., was a J.P and a surgeon.

Other leisure activities are the Athenaeum Newsroom and Library in London Street, the Museum of Natural History in Aughton Road, The Young Men’s Christian Association in the Palatine buildings, which appear to have been on the corner of Lord Street and Neville Street, the Cricket Club, the Church Institute and Newsroom in London Street and the New Club in Bath Street.

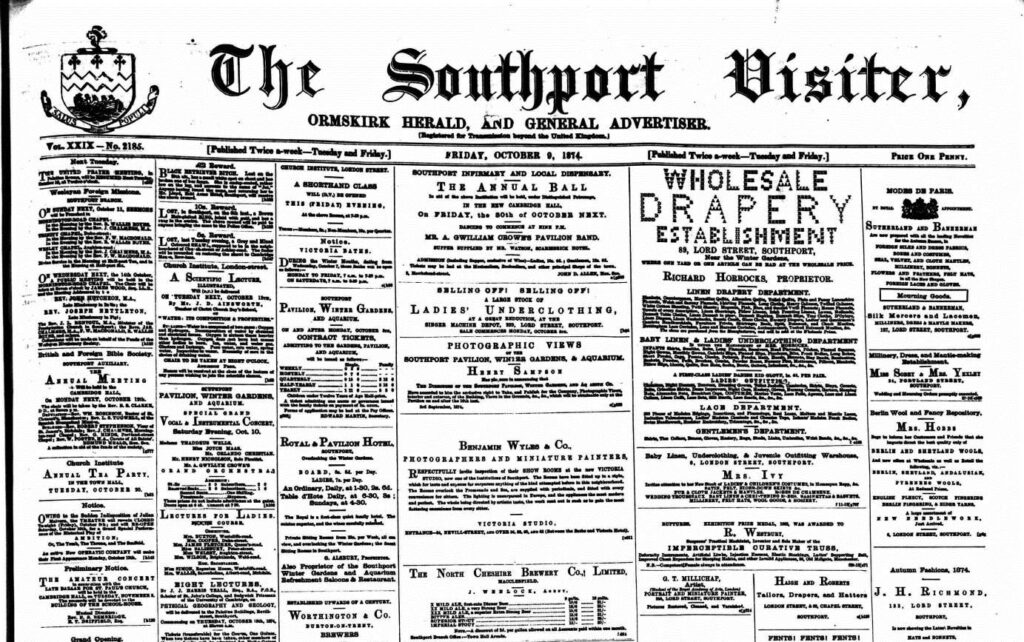

Given the number of reading rooms it is interesting to note the town had two newspapers. The Southport Visiter, established in 1844, was published on Tuesday and Friday, price 1d, and The Southport News, commenced in 1861, was published on Wednesday and Saturday, again price 1d.

At this time the paper was four pages in length and one page was devoted to listing the names and lodgings of visitors to the town.

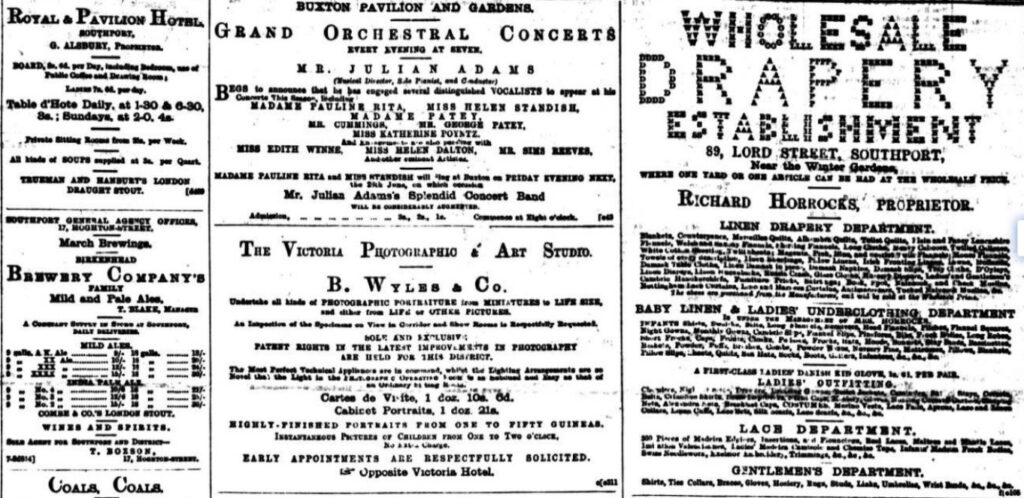

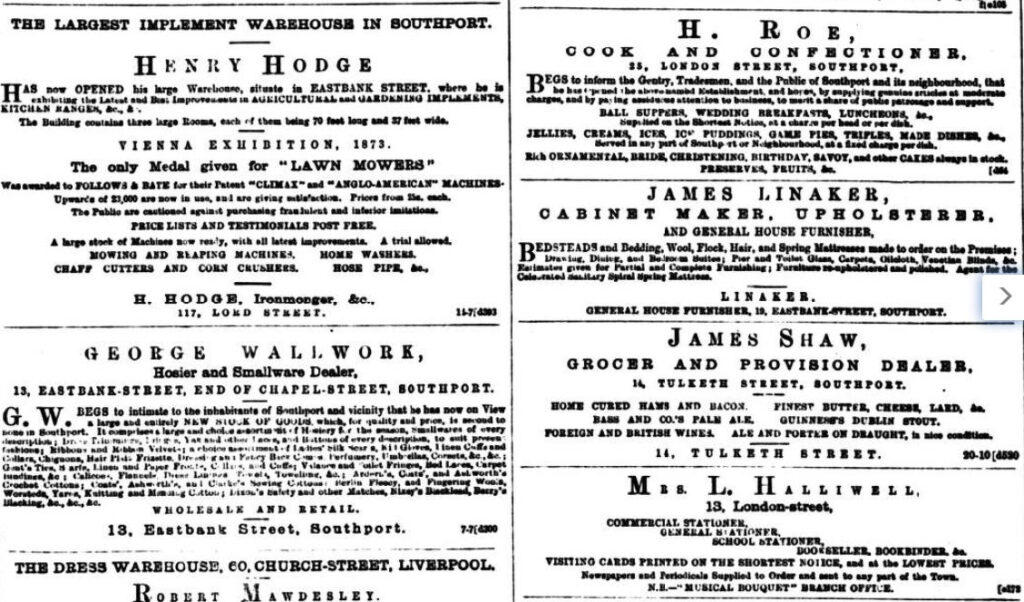

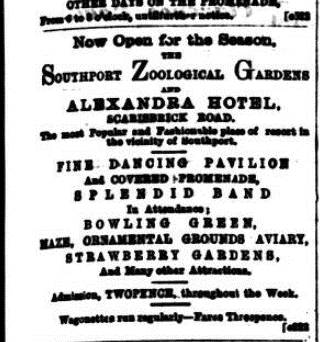

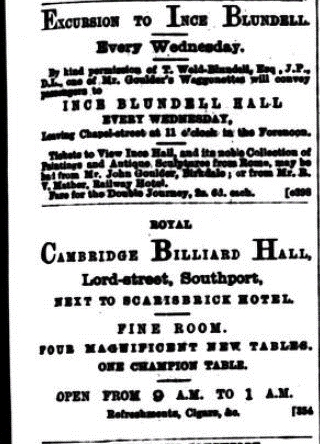

A selection of adverts taken from the front page of the Visiter in June 1874 help to give a flavour of what was on offer.

This period is perhaps best summed up using the words of Harry Foster from his book Southport: A History: “The 1870s saw a period of unprecedented growth in Southport, with the Heskeths, the Scarisbricks and the Weld Blundells granting increasing number of leases. A minority of Southport’s wealthy residents continued to live in the increasingly commercial town centre, but many now chose to live in Hesketh Park or Birkdale Park areas.”

On Lord Street itself, the Council, and wealthy benefactors such as William Atkinson, demolished further houses to build more Municipal buildings. By 1880 this impressive suite of civic buildings was set off by newly landscaped gardens and each year saw a further maturing of the canopy of trees on Lord Street’s “inland boulevard”.

This then was the town which was to give birth to the University Extension movement later in the year.

Sources:

- Southport Directory 1872-73. Crosby Library.

- Bailey, F.A. The Town Planning Review Vol 21 No 4 pp299-317, 1951.

Note: Images of Old Southport are copies from Bailey2 and the newspaper images are from the British Newspaper Archive.

Mary Ormsby

Contacts

Chair: Alan Potter

alanspotter@hotmail.com

07713 428670

Secretary: Roger Mitchell

rg.mitchell@btinternet.com

01695 423594 (Texts preferred to calls)

Membership Secretary: Rob Firth

suesmembers74@gmail.com

01704 535914

Forum Editor: Chris Nelson

chris@niddart.co.uk

07960 117719

Facebook: facebook.com/groups/southportues

See our archive for previous editions of the SUES Forum!