Introduction

We have reached an important stage in the development of SUES. The Society has been kept going throughout the months of Covid restrictions by means of this FORUM and several Zoom meetings. Recently we ventured out for a face-to-face gathering – in the open air. You will find a report on this below. We hope now to hold an indoor meeting and to announce a programme for 2021-2.

Annual General Meetings are not always the most enticing events, but this one is particularly significant, and we hope that as many of possible of you will attend. Details are given below, and the papers for the AGM, including reports from Chair and Treasurer, are in a separate attachment to the email that brought you this edition of FORUM.

There is just one article in this edition. It is an extended essay by Peter Firth, who looks at history from an unusual angle, that of the pomegranate. We are sure that you will find it both entertaining and informative.

Annual General Meeting

At 2.30 pm on Friday 23rd July 2021

This is to confirm that the SUES AGM will be a real event and will take place at 2.30pm on Friday 23rd July at All Saints’ Church Hall, Southport PR9 9JR (Car Park and Entrance via Park Rd).

We will be using the large hall which has plenty of space and excellent ventilation. Even though Covid restrictions may no longer be mandatory, the room will be laid out to ensure social distancing and everybody attending is requested to wear a facemask.

As well as the AGM, there will be contributions from members about the positives of 2020 – 2021, things like gardening, reading and keeping in touch with friends.. Any additional contributions on the day will be welcomed. Refreshments will be provided without charge and we aim to finish between 3.30pm and 4pm.

We realise that not all members will be able to attend, but whether you come or not, because this is the first step to our 2021-2 Programme, we would be very grateful if you could tell us how things are with you. If you can, please send a text, email, phone call, card or letter to Alan, John or Roger (Contact details below). Please tell us whether you will be at AGM and whether you hope to return to Society (and to SUES) in the coming season. We very much hope that you will be able to tell us that things are well with you. Unless you prefer to stay anonymous, we would like to give this update on members at the AGM and in the August Forum.

We very much look forward to seeing you on 23rd July or hearing from you sometime soon.

Lichens and Cream Tea!

Our first face-to-face gathering for over a year took place on Friday 18th June and was a most enjoyable event. We met in Victoria Park and under the expert direction of Alan Potter looked for lichens on the trunks of trees. We were all struck at how a closer look revealed just how many lichens were around and how varied they are. Trees, which normally one would walk past without a glance, turned out to be full of interest. We even began to gain confidence in identifying the main types and in some cases the genera. Not only did we spend part of a sunny afternoon in this pleasant way, but we were also invited afterwards to enjoy cream tea in Helen and Martin Perry’s delightful garden. It was amazing to find this gem in residential Southport. Surrounded by trees, shrubs and flowers in a beautifully-arranged setting, it was like a secluded nook in the countryside. We are grateful to them for their hospitality and to Alan for arranging this memorable event.

John Sharp

History of the Pomegranate

Introduction

Until the last few decades, the pomegranate had not been a horticultural or botanical icon in the western world but, with its growing reputation as a super-fruit, the health-giving and distinct flavour properties of this remarkable fruit are becoming increasingly acknowledged.

Previously, the historical importance of the pomegranate has often been understated. It, therefore, seems appropriate to understand more about the fruit’s origins and its impact and importance in human society over the preceding millennia. This account attempts to provide a brief appreciation of the pomegranate’s role in various civilisations and cultures throughout world history.

Historically, the pomegranate has had a deep association with the Mediterranean and cultures in the Near East where, because of its dietary component and major contribution to cuisine, the fruit’s unique combination of sweetness and acidity is considered as a highly regarded delicacy. In many areas of the world, the pomegranate has for centuries been greatly valued for its medicinal and therapeutic qualities, together with its ornamental value. It has been known to humans from antiquity, since when it has been widely revered for its symbolism which is as multi-faceted as its beneficial health effects.

Cultivation and Trade

Originally a native of the land extending from modern day Iran to northern India and, reflected in Assyrian motifs as possibly being the ‘apple’ of the biblical Garden of Eden and the Tree of Life, the pomegranate had been extensively traded around the Mediterranean for centuries before the emergence of the Roman Empire.

Thought to be one of the first five edible fruit crops, along with the fig, date palm, grape and olive, its possible domestication took place in the fifth millennium BC, from when it has been identified in Bronze Age records in Jericho and Cyprus. Of great significance, such archaeological discoveries were primarily in elite residences, indicating the importance of the pomegranate’s status in contemporary society. Mesopotamian cuneiform records from the third millennium BC confirm its existence. It is also recorded that the Babylonians believed that chewing its seeds before battle made them invincible. Moreover, a fourteenth-century BC shipwreck, Ulu Burun, found off the coast of Turkey in 1982, contained luxury items which included pomegranate remains, indicating its trade across the Mediterranean. It is thought that the fruit’s cultivation spread along the Silk Road to the Far East, reaching China by 100 BC.

Due to it being highly adaptive to a wide range of climate and soil conditions, the pomegranate tree has been grown in different tropical and sub-tropical regions across the globe. The opportunity to extend its availability even further arose in the sixteenth century when Hernando Cortés was probably responsible for its plantation in the New World in Central and South America. From there, its cultivation spread to the USA, finding a late eighteenth-century foothold in California, now a major source of pomegranate world production. Attested by the explorer, George Vancouver, the first Englishman to reach Spanish California in 1792, he noted in his journal the abundance of pomegranate trees at Mission San Buenaventura in Ventura, California. A pomegranate-themed fresco at the Mission San Miguel Archangel also confirms pomegranates thriving in California’s early history.

Etymology

Often referred to as the “Phoenician Apple”, because of its Levantine origin from where it had originally been exported to North Africa, the pomegranate’s name harks back to the Roman name for the Phoenician colony of Carthage (Latin adjective: punicus) in modern Tunisia. From this, the name of its principal component, punicic acid, derives. Large quantities of pomegranates – malum punicum, the apple of Carthage – were exported to Roman territories.

In Old French, a pomegranate was referred to as pomme-granade, from which is derived the word for a military grenade, because of its similarity in appearance. Despite some confusion, there is no linguistic connection with the Spanish city of Granada whose name is Arabic in origin, although there is a very close historical link with the city (see below). The semi-precious garnet, with its dark red colour, has also been related to the fruit because of its Latin name, granum, or red dye. Although the English word “pomegranate” takes its origin from medieval Latin as a “seeded or grainy apple”, it was in the eighteenth century when Carl Linnaeus, the Swedish botanist and father of taxonomy, gave the fruit its official botanical name, punica granatum.

History

Ancient Egyptians

Evidence indicates that pomegranates were first grown in Egypt in the early New Kingdom (eleventh to sixteenth centuries BC). But since examples have been found in earlier Middle Kingdom tombs – mainly associated with aristocratic and priestly classes – travellers must have known about this fruit for some time before being successfully grown in Egyptian gardens.

In fact, for millennia, it has been recognised that the pomegranate provided a well-protected source of liquid refreshment to early desert travellers, staying fresh for months without the need for any refrigeration. The fruit’s juice could be available by drinking straight from the hard shell, pierced with a skewer-type object, ideally by inserting a straw. The lack of any refrigeration requirement also made the pomegranate a perfect item for trade.

The first mention of a pomegranate tree in Egyptian inscriptions comes from the tomb of Ineni, an official at the court of King Thutmose I, who recorded all the different types of trees that he wanted to have planted on his estate. It is likely that the king had brought the fruit back with him from his military campaigns into central Asia. Later, Thutmose III depicted pomegranate plants at the Karnak Temple, in a room now known as the Botanical Gallery.

Nineteen pomegranates were also discovered on glazed ceramic tiles in the tomb of Amenhotep II. Two pomegranate amulets have also been found in the Osirian temple inscriptions at Denderah. Here, a link between Osiris and resurrection has long been understood. This theme also occurs in later Coptic pomegranate artistry, developing from simple ornamental motifs into fully incorporated symbolic representation of Christ’s suffering which became commonplace in the Middle Ages. The fruit’s shape is easily recognised among the offerings of food represented at other Egyptian places of worship, such as at the Abydos Temple of Sety I, where the king is shown offering to the gods a tray of bread, fruit and roast ducks. In the centre of this appetising meal is a pomegranate, painted in realistic colours.

Ancient Egyptians were also buried with the fruit, as found in a single complete desiccated pomegranate among the food offerings left in the tomb of Djehuty, an estate-overseer, who served Queen Hatshepsut in the fifth century BC.

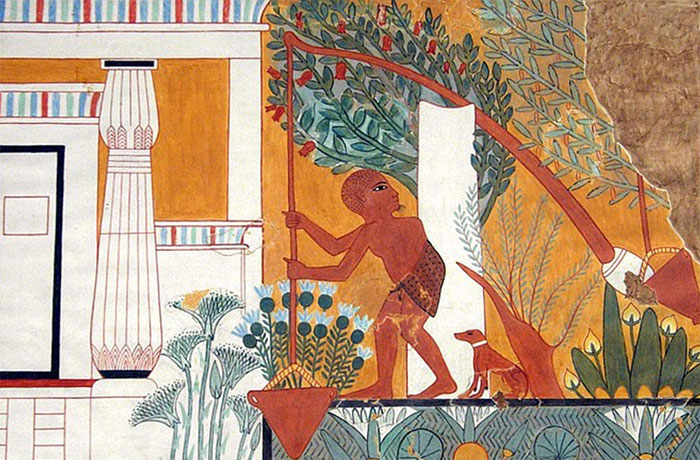

As to cultivation, in the famous tomb painting of Ipuy, the royal sculptor, a gardener is shown, working a shaduf to raise water (Fig. 1). The pomegranate tree can be clearly identified by its trumpet-shaped red flowers as one of the trees that provide fruit, but also much-needed shade in Egyptian gardens.

When Tutankhamun’s tomb was sealed in 1323 BC, pomegranates symbolised the promise of an afterlife. Of the 5398 artefacts found there was a large silver vase in the distinctive shape of the pomegranate fruit (Fig. 2), together with a painted ivory pomegranate spoon.

Engraved around the body of this vase is a frieze of pomegranate flowers whose leaves were woven into a garland. An elaborate funerary collar was also placed around the king’s mummy.

Various academic studies provide many other Ancient Egyptian examples of pomegranates being represented by pendants, as well as food offerings, decorative devices, vases, medicinal remedies, in addition to the fruit as wine. Pomegranate-like pendants have been found in several tombs, such as the chaplet on the head of the mummy of Queen Meryet-Amun in Thebes.

Similarly, love poems relating to the pomegranate tree were discovered at Deir al Medina, near the Valley of Kings, revealing emotional and sensitive phrases similar to those used by more modern poets, such as the female narrator of a poem, written on papyrus, which compared her lover’s voice to pomegranate wine.

In a much later period of Egyptian history, the 1987 archaeological dig at the Graeco-Roman Fag al-Gamous necropolis, from around the fourth to fifth centuries AD, revealed a pomegranate tapestry covering the head of a young child (Fig. 3).

This clearly shows in cross-section the seeds and pithy membrane of the plant. The positioning of the body pointing towards Jerusalem strongly suggests a Christian burial for which the pomegranate is again seen as a reference to the resurrection of the dead and afterlife – associations that became a strong focus of subsequent Christian imagery.

Jewish/Biblical Associations

There is a close connection between the pomegranate’s Arabic and Hebrew names (rumman/rimmon). Many place names incorporate the Hebrew word, such as Ein Rimmon (Spring of the Pomegranate), Sela Rimmon (Rock of Pomegranate), Beit Rimmon (House of Pomegranate) and the simple Rimmon (Pomegranate) – clear evidence of the fruit’s geographical importance. There is also a linguistic connection with the Syrian storm god of fertility, Hadadrimmon (Haddad or Haddu of the Pomegranates).

In the Bible, the pomegranate is the first fruit of the season – a symbol of peace, abundance, knowledge and a metaphor for a woman’s beauty. It is often referred to as the perfect fruit with 613 seeds, the number of mitzvot (commandments) in the Torah, symbolising fruitfulness, with its seediness, encouraging the association with fertility.

In Exodus 28:34 (KJV), the high priests in the Temple are referred to as wearing vestments with pomegranates embroidered onto their hems. They also appear on the adornment on the capitals of two pillars in King Solomon’s Temple (1 Kings 7:18). Actual examples were brought to Moses by scouts to demonstrate the fertility of the Promised Land (Deuteronomy 8:8). Judean coins from the second century BC contained an image of the pomegranate on one side – a symbol of wealth and plenty. More recently, the 2007 Israeli two shekel has a similar image. In addition, the Jewish tradition of a “calyx”, which forms a protective layer around the pomegranate flower in bud and appears on the rind, is a symbol of the perfect crown of a monarch.

The Song of Solomon includes the most potent and erotic symbol of the pomegranate. Sheba says to the king: “Let us get up early to the vineyards; let us see if the vine flourish, whether the tender grape appears and the pomegranates bud forth: there will I give thee my loves” (7:12). Later, she urges Solomon to drink “the spiced wine of the juice of my pomegranate” (8:2). Previously, Solomon described his bride as a garden whose “plants are an orchard of pomegranates” (4:13) with “temples…like a piece of a pomegranate within thy locks” (4:3).

Today, in Jewish tradition, the pomegranate is blessed as the first fruit of New Year on a Rosh Hashanah table. It represents the sign of fertility, peace and prosperity for the new year, confirmed in the prayer: “In the coming year, may we be rich and replete with acts inspired by religion and piety, as the pomegranate is rich and replete with seeds”. In contrast, today’s Israeli army uses the term for a hand grenade as rimon yad (hand pomegranate).

Ancient Greece

The pomegranate was the love symbol of the goddess, Aphrodite. The “Sacred Fruit” was also referred to as the “fruit of the dead”, having sprung from the blood of her mortal lover, Adonis, as well as providing sustenance to residents of Hades in the Underworld. From this emerges the myth of Persephone, the daughter of Zeus and Demeter where no other plant depicts Persephone’s fate or the fate of the world, as does the pomegranate.

In one version of the so-called Eleusinian Mysteries, Persephone is kidnapped by Hades to live as his wife in his underground domain (Fig. 4).

Demeter, the goddess of the Harvest, is distraught at the loss of her daughter and abdicates her godly duties over vegetation and plant growth. All green things cease to grow because Demeter resolves to prevent the earth from seeing any fruit or plant life, unless and until she can see her daughter again. Zeus decides that he cannot allow the earth to die and, with the increasing likelihood of human demise, he commands Hades to return Persephone.

However, by the Rule of the Fates, anyone consuming food or drink in the Underworld is doomed to spend eternity there. With no other food available, Hades elects to offer Persephone a pomegranate as a compromise. She would then live with him, spending six months in the Underworld every year, sitting on the throne at his side. During this time, she agrees to eat six seeds, representing the time of no growth, returning each year to mark the arrival of spring. This myth was also to act as a symbol of the indissolubility of marriage. More importantly, it provided the ancient Greeks with an explanation for the seasons.

Written around 600 BC, Aesop included The Pomegranate, the Apple-Tree and the Bramble within his Fables. There are other Greek stories and myths which refer to the pomegranate, including one about the Persian king, Xerxes, who in 480 BC attempted to capture Greece with an army carrying spears adorned with pomegranates as a symbol of their strength-giving qualities.

Roman

The pomegranate was frequently depicted in mosaics, as in the house of a fruit orchard in Pompeii. Another, found at Hinton St Mary in Dorset, depicts a bust of Christ flanked by pomegranates (Fig. 5).

Twigs of these were worn as headdresses by Roman women to signify their marital status. Besides cures for scorpion stings and morning sickness, Pliny the Elder describes in Naturalis Historica, the use of the fruit’s rind as a perfume ingredient, with the juice used as an astringent to prepare an “essential” oil to fix a scent.

Reconquista, the Pomegranate Conquerors & Catherine of Aragon.

In 1492, after seven and a half centuries of Muslim rule, King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain finally conquered Granada, the last non-Christian stronghold in Andalusia. According to local tradition, Isabella stood with a pomegranate in her hand, declaring “Just like the pomegranate, I will take over Andalusia seed by seed.” As a result, the coat of arms of the city incorporated the fruit. A commemorative glass flask, painted with a crown and pomegranate and marked with the date 1492 and the words Granada and America appeared ca.1592, to celebrate the intervening century.

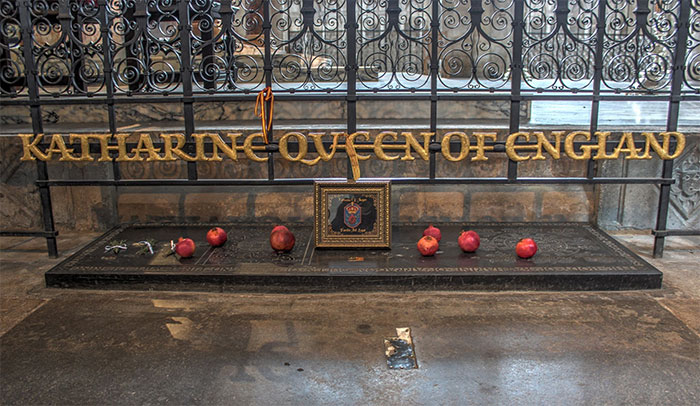

Catherine of Aragon, their daughter, had a pomegranate insignia as her heraldic emblem (Fig. 7).

This featured prominently during Henry VIII’s early reign and, as a result, would have helped popularise the fruit in England. The union appears on a crest of both spouses (Fig. 8). The pomegranate of Granada and the Tudor Rose were frequently found adorning the royal palaces.

Gilded pomegranates were used during the festivities surrounding their wedding ceremony and the queen’s coronation (Fig. 9).

It was also alleged that, alongside a rose tree to represent the House of Tudor, Henry planted the first pomegranate tree in Britain – unsuccessful, in many ways. After her death, Catherine was buried in Peterborough Cathedral where her tomb is regularly covered in pomegranates (Fig. 10).

Holy Roman Emperor

In 1519 during his coronation, Maximilian I was depicted holding a pomegranate, in the same way a monarch usually held an imperial orb at their coronation, as a symbol of cohesion in diversity throughout the Holy Roman Empire. The grains represented his subjects. This symbol was later to become his personal emblem (Fig. 11).

Reformation and the European Wars of Religion

In 1598, Henry IV of France issued the Edict of Nantes, whereby religious freedom was granted to all citizens, in doing so ending the violent civil war between Catholics and Protestants. Baptised a Catholic but raised in the Protestant faith as a Huguenot, Henry had led armies against Catholic forces. After assuming the French throne, he eventually converted to Catholicism. To represent this contradiction and tolerance, Henry’s heraldic badge, incorporating the pomegranate, appeared with the motto “sour, yet sweet,” reflecting the nature of the fruit while, at the same time, attempting to demonstrate the king, in a judicious reign, tempering severity with mildness.

French Revolution

Post 1793, the new regime attempted to reinvent a Republican twelve-month calendar, with Fructidor (August/September), portraying the image of a Virgin holding in her hand an open, bursting pomegranate as a likely allusion to associate it with chastity, fruitfulness and harvest. (Fig. 12). The calendar itself survived barely more than a decade.

Napoleon II’s Extremely Short Reign

Emperor Napoleon married Marie-Louise of Austria, after Josephine had failed to produce a male heir. The resultant son, also named Napoleon, was given the title, King of Rome, and, for a few weeks, tried to succeed his father in 1815, but was never recognised by the victors of Waterloo. Like Maximilian I, instead of holding an orb during a coronation, Napoleon II was also depicted holding a pomegranate (Fig. 13). This was the closest the young monarch ever came to wielding actual power.

Twenty-first Century

In Armenia today, the bride is given a pomegranate to throw against the wall, breaking into pieces, as a sign that the scattered seeds ensure future children. Similarly, in traditional weddings in Cyprus, a pomegranate is thrown in the path of newly-weds to assure plentiful posterity. In modern Greek symbolism, the pomegranate features as a house guest’s first gifts in a new home to represent abundance, fertility and good luck. The pomegranate featured as the symbol of the 2015 European Games in Azerbaijan. One of its two mascots, Nar, also featured on the jackets of its country’s male athletes.

In the USA, pomegranates are in widespread use in table arrangements. This is especially common during the Thanksgiving and Christmas seasons with frequent inclusion in paintings, graphic design and architecture. It has been estimated that much of the fresh fruit purchased in the USA is rarely consumed but used primarily for ornamental or aesthetic reasons.

Religion

Zoroastrianism

This ancient religion regards the pomegranate as a symbol of fecundity, immortality and an emblem of prosperity. It has also been used as a basic tenet of belief concerning the constant battle between good and evil because of the fruit’s sweet and sour properties. It is mainly associated with fertility but also appears, representative of the vegetable world, providing mankind with food. As further recognition of this, trees were planted in courtyards with their leaves remaining green most of the year, representing a symbol of eternal life. One of the religion’s legendary heroes, known as Isfandiyar the Invincible, acquired that attribution after eating a pomegranate. His feats included slaying various real and mythical creatures, as well as winning several battles.

Hinduism

This notion is also associated with the festival Durga Puja, dedicated to the goddess Durga (also known as Shakti or Devi), whose name also means invincible, battling the forces of evil in the world. She is the protective mother of the universe, of all that is good and harmonious, and one of the faith’s most popular deities, On the ninth day of the celebration of her various manifestations – Ma Siddhidhatri – apples and pomegranates are specifically offered as fruits. The pomegranate also appears as a symbol of prosperity and fertility in the Vedas, one of the oldest texts in Hindu literature.

Islam

The pomegranate (ar-Rumm, in Arabic) appears three times in the Koran (Surah Al Anaam, chapter 6, verses 99, 141: Surah Ar-Rahman, chapter 55, verse 68). Its supreme importance, with dates and olives, is underlined as being one of the delicious rewards found in paradise. Together with these fruits of the earth, pomegranates speak of the dues to be paid upon each harvest. Mohammed recommends this fruit, as it purges the system of envy and hatred, as well as being a precious fruit, filled with nutrition, bringing emotional and physical peace.

Buddhism

One encounter with the Buddha refers to wealthy disciples presenting lavish gifts. At the same time, an old, poor woman, having travelled many miles, presents just one small pomegranate as her gift, before collapsing at his feet. To the surprise of others there, the Buddha rings the bell of honour in her name, considering it the greatest gift – more than gold and jewels. The pomegranate is a symbol of fertility and also one of three blessed fruits which are the essence of favourable influences in Buddhist art. This is typified in the mandala (Fig. 14), a circular symbol representing the universe, often used in meditation.

Christianity

Papal Protector

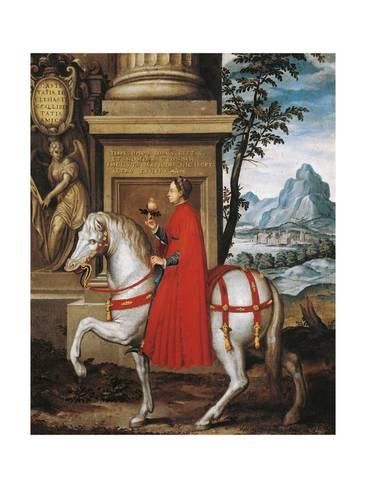

Matilda, Countess of Tuscany, was one of the great power brokers, peacemakers and warriors of eleventh-century Italy. Already a major supporter of the popes, she put all her military and material resources into the service of the papacy from 1080, during a dispute between Pope Gregory VII and the German king, Henry IV, allegedly leading armies against him. She is one of a very few women buried in St. Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican – the first-ever non-pope buried there when her remains were transferred there by Pope Urban VIII in 1634. Matilda has been the subject of many myths and artistic representations and, although married at least twice, has been depicted on horseback holding a pomegranate, a symbol of her virginity (Fig. 15).

Serafina dei Ciardi’s Death, 1253

In Christian iconography, pomegranates symbolise the promise of the afterlife. Here (Fig. 16), a bowl of the fruit is on the table above the golden halo of Serafina, as she was known who, aged 15, died after suffering a paralysing illness and losing both parents. Knowing true suffering, pomegranates signify she would soon know new life.

Virtues of the Virgin

The pomegranate also played a central role in terms of Christian symbolism. Throughout the Renaissance, such artworks often represented the blood and Resurrection of Christ, as well as symbolising the Church, enclosing its followers. They also represented the many virtues of the Virgin Mary.

Often, the fruit in the Infant Jesus’s hand or hers, broken or bursting open, symbolises Christ’s suffering, his Resurrection and life-everlasting, as well as hope, plenitude, spiritual fruitfulness and, equally, the Virgin’s chastity (Fig. 17).

Pomegranate and Eternal Life

Similarly, held in the left hand of Jesus, the pomegranate can also be found elsewhere as a Christian symbol of eternal life (Fig. 18).

Pomegranate Stigmata

Pomegranate arils (seeds), spilling from the hand of Jesus, like drops of blood can be seen as symbolic stigma, suspended in time (Fig.19).

Art History

Aside from religious decoration of the pomegranate frequently appearing elsewhere, woven into the fabric of vestments, liturgical hangings and wrought metalwork, it has also been included in many secular works of art, together with household objects, as well as plays.

Fertile Imagination

Pomegranates have long and frequently represented a symbol of fertility. Here, the mother might be overwhelmed by her abundant fertility of offspring, by plucking a pomegranate… or might desperately be trying to put one back (Fig.20)!

Muse and Myth

Painted as a goddess eight times, Jane Morris was the model used in a depiction of the Roman goddess “Proserpine” (Greek mythology, Persephone), condemned to the underworld with pomegranate seeds. (Fig.21).

Pomegranates and Art Revolution

By holding one’s hand in front of one’s face and focusing on the background, the hand becomes doubled (Fig.22). Cézanne sought to depict this phenomenon in a single composition, as shown in his imagery, with two pomegranates. This experimentation led to the birth of cubism, modern art and, potentially, Picasso.

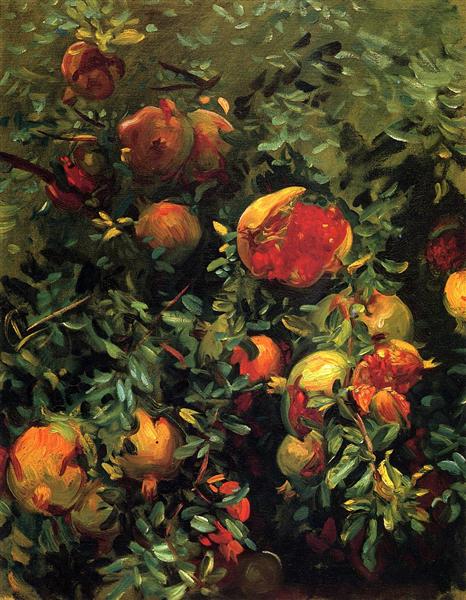

Majorcan Retreat

Having previously been paid handsomely for painting leading contemporaries of American society, one prominent American portraitist found peace, quiet and pomegranates on this Spanish island, painting outdoors (Fig.23).

Proserpina’s Refusal

In Nathaniel Hawthorne’s book of short stories, The Tanglewood Tales, a section entitled The Pomegranate Seeds is accompanied by an image of the initial refusal of Proserpina of a pomegranate – the last piece of fruit in all the world – offered to her in the palace of Pluto (Fig. 24).

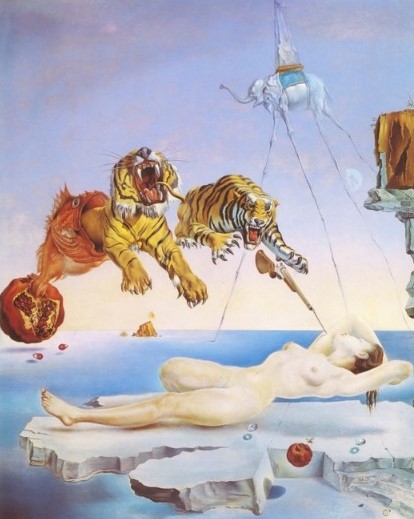

Dalí’s Pomegranate Dream

One of his “hand-painted dream photographs”, this image shows two pomegranates, two tigers, an elephant with stilt legs, a bayonet, and his wife, Gala, illustrating complex narratives, created instantaneously in dreams (Fig. 25)

Practical Artistic Influences of Pomegranates in Meals

By the eighteenth century, the pomegranate had been put to more practical purposes of artistic expression, both in France under Louis XV and in England under George II, often adorning ornate soup tureens as its handle, with the first course designed to impress guests around the meal table (Fig 26).

Silver Soup Tureen, approx. 15” length, 5lb weight

Shakespeare Romantic Pomegranate Imagery

Act 3 Scene 5: Having probably first consummated their love, Romeo and Juliet head to the balcony and discuss a bird singing in “yon pomegranate tree.” A lark signifies it’s morning and Romeo must leave; a nightingale signifies it’s night and he can stay longer. Alluding to this symbol of fertility, the imagery created reflects the role of the pomegranate tree in terms of Romeo and Juliet’s first night together.

Pomegranate’s Properties

In addition to being used for several millennia in the field of human health, pomegranates have, for equally as long, been employed in many non-medical areas. Bark tannins are still used today in Moroccan leather. Extracts of its flowers and fruit husks are used as textile dyes. Its rind extracts were used as a major source of ancient and medieval ink because of its deep pigmentation and continue as a speciality of craft inks today.

Ancient Medicinal Properties

ca. 1550 BC the ancient Egyptians used the tannin of pomegranates as a source of rich fruit extracts for the riddance of tape worms. Around 400 BC, Hippocrates utilised various extractions for a wide number of ailments e.g. skin and eye inflammation and as an aid to digestion. Pedanius Dioscorides (40-90 AD), a Greek physician who travelled with Nero’s army, recommended in De Materia Medica – at the time the leading pharmacological book – pomegranates as a “pleasant taste and good for the stomach… [the juice to be used for] ulcers and for the pains of the ears and the griefs of the nostrils.” Pomegranates were frequently employed as a “fruit of love” potion. Other traditional uses included treatment for contraception, snake bites, diabetes and leprosy. Tannin was extracted from tree bark; its leaves and immature fruit were used to combat diarrhoea and bleeding. Dried, crushed flower buds were recommended as a tea for bronchitis. Much later, extracts of flowers were used in Mexico as a gargle to relieve mouth or throat inflammation. Many of these uses have been supported, at least in part, by recent scientific studies.

Medieval Medicinal Properties

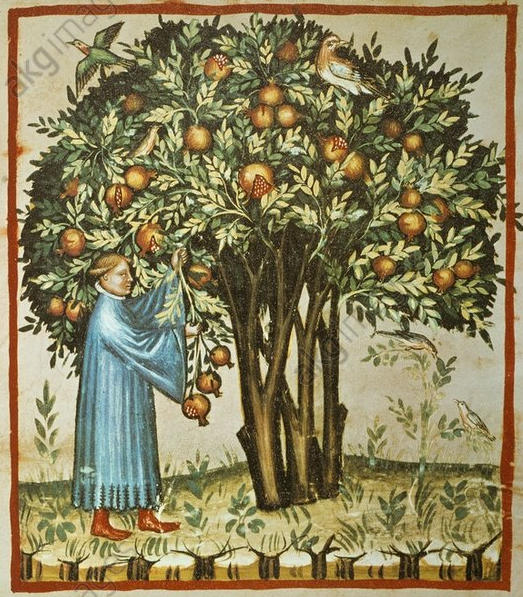

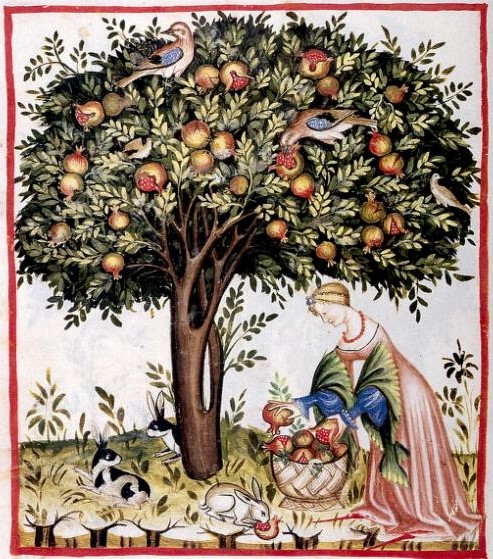

The Tacuinum Sanitatis was an illuminated guide for health and horticulture commissioned by northern Italian nobility during the 14th century. It amalgamated centuries of medical writing, principally from the eleventh century Christian Arab, Ibn Butlan, and including the works of Hippocrates (c. 460-370 BC). The elegant gothic clothing, illustrated throughout the book, indicates that its contents were reserved for the privileged, particularly as some of the fruits, such as pomegranates, were considered a luxury food. They were recommended for an inflamed liver, against coughs and for coitus. So important was this item that three separate images were reserved for it, including both sweet and sour varieties (Fig. 27).

Collecting Sour Pomegranates

Inspecting Sour Pomegranates

Inspecting Sweet Pomegranates

Modern Medicinal Properties

Reminiscent of precious jewels, the arils of the pomegranate contain not only juicy seeds but, within the seed itself, is an equally precious oil, as well as other essential nutrients. Extensive research has shown that nearly all of the seed’s oil is made up of fatty acids of which punicic acid (also referred to as conjugated linolenic acid), a rare Omega 5 fatty acid, constitutes by far and away the major part. Pomegranates are the only known plant-based source of Omega 5. Scientific studies, available across many media, claim that this so-called “fountain of health and youth” can have a positive impact on many of the body’s systems – metabolic, immune, circulatory, hormonal, digestive, etc. It also has great healing effects on the body’s largest organ – skin – being antioxidant, anti-ageing and anticarcinogenic.

Little wonder that, in recent years, the remarkable fruit from which this oil stems has in a matter of years undergone a major horticultural reassessment because of its wide application as a “wonder” ingredient in the medical, cosmetic and pharma industries of the twenty-first century which, together with its association over several millennia with human beings, lend support to the recognition of its significant importance amongst the many fruits on our planet, provided by Mother Nature.

Peter Firth

Contacts

Chair: Alan Potter

alanspotter@hotmail.com

07713 428670

Secretary: Roger Mitchell

rg.mitchell@btinternet.com

01695 423594 (Texts preferred to calls)

Membership Secretary: Rob Firth

suesmembers74@gmail.com

01704 535914

Forum Editor: Chris Nelson

chris@niddart.co.uk

07960 117719

Facebook: facebook.com/groups/southportues

See our archive for previous editions of the SUES Forum!