Introduction

Welcome to Forum 47. SUES’s 2023-2024 programme commenced on 15th September with Emma Copestake’s talk on her oral history study among retired Liverpool dock workers and their families. We have a report in this issue of Forum for those of you who were unable to attend.

Peter Firth’s course Medieval Bookends commenced on 25th September and continues on Monday mornings through October and November. I, for one, am really enjoying this course, and am certainly improving my understanding of this period of our country’s history.

This issue includes Cash for Coronets, an engaging article from Mary Ormsby on the late 19th and early 20th century phenomenon of American heiresses marrying into the European aristocracy.

We also have a report from Alan Potter and Peter Firth, who recently represented SUES at a celebratory dinner at Cambridge University to mark the 150th anniversary of the Institute of Continuing Education.

Since becoming Editor of Forum earlier this year, I have been looking back over earlier issues. Forum was started during the pandemic lockdown, to maintain SUES’s educational role and to help members keep in touch during that difficult time. The first issue stated that: “We have called it a Forum, because we are hoping for a response. We would like to receive your comments, further thoughts, suggestions and, if possible, contributions.” I would like to repeat that request here: your articles, poems, book reviews, anecdotes, general musings and (of course) suggestions for improvement are all welcome. Many thanks to those who have already offered a contribution – please keep them coming!

Chris Nelson

Coming Up in October 2023

Friday 27th October at 2:30 pm

All Saints Church Hall, Park Road, Southport, PR9 9JR

Talk by Eric Woodcock

Lankie ‘Leckies – Electric Vehicles from the 1880s to the Present Day

Liverpool’s Dock Community During the National Dock Labour Scheme 1967 – 1989 – Emma Copestake

A report on the meeting held on 15th September 2023

It was good to be back at All Saints for the first talk in our 2023-24 session, which was given by Emma Copestake. Following an introduction from Peter Firth, Emma took us through her work on an oral history project (the subject of her recent PhD thesis) among the Liverpool dock community.

She began by discussing oral history in general, observing that it once had a poor reputation for being ‘unreliable’, but this had changed in the 1970s with pioneering work on labour history and women’s history. There had been two previous oral history projects within the Liverpool dock community: the Mersey Heritage Project in the 1980s, and a further project during the Liverpool dockers’ dispute of 1995-98, both based on interviews with working people. Emma’s more recent work has involved talking with retired dock workers and their families. She explained that oral histories obtained in this way are not necessarily ‘accurate’ (when compared with historical documentary information, for example) but are intended to supplement the ‘facts’ with an appreciation of the memories, opinions, attitudes and emotions of people living and working in the community being studied.

The National Dock Labour Scheme had been introduced by the post-war Labour government in 1947. It reduced the casual nature of employment in the docks by registering regular dock workers and paying them a basic wage if they signed in, whether or not there was work for them on a particular day. Further improvement in the terms of employment came in 1967. With the opening of the Seaforth container terminal in 1972, and the decline of traditional cargo handling, the nature of dock work changed and fewer workers were required. The number of registered dock workers in Liverpool was 10,449 in 1970 and had fallen to 4,614 by 1980. Much of the (non-container) dock estate ceased operating during the 1980s and the National Dock Labour Schemewas abolished in 1989. Since 1994 there has been a new scheme involving a 3-weekly pattern of work schedules and industrial disputes have been relatively rare.

Jobs in the docks were passed down through families and the semi-casual system of employment meant that everyone’s income was unpredictable, so people supported one another within the community; this was a common theme, mentioned by many of the people interviewed. There was a general desire to make dock work secure for future generations and “a kind of macho comradeship”.

There was a tradition of giving individual workers a nickname, reflecting some aspect of their personality. Emma suggested that this allowed for spontaneous moments of humour, resisted the notion that the workforce was a uniform pool of labour, and served to ‘socialise’ new members of the workforce to regulate their behaviour and ensure that they pulled their weight.

Some of the interviewees revealed ‘tricks of the trade’ such as ‘The Welt’, an infamous practice in which the gang was divided into two groups, each of which worked for half of the day, with everyone being paid for a full day; the stated objective was to protect jobs. There was also a tradition of pilfering. With its origin in a time of great poverty and casual employment, this was seen by some as a right, and not as theft or a perk or the job. However, there were limits and the practice was, to an extent, policed within the community. The Port Police were known as ‘pantomime bobbies’ and the dockers liked to outwit them. Understandably, many interviewees were reluctant to talk about these matters. However, there was also an element of organised crime in the docks and most interviewees viewed this negatively.

A popular subject was health and safety (or the alleged lack of it). One of Emma’s interviewees had referred to the “mentality of casualisation” – arguing that, because the dock workers were paid on a piecework basis, there was an incentive to cut corners with regard to safety. One worker said that there was no health and safety provision during his employment between 1959 and 1981. This is not necessarily accurate: the Health and Safety at Work Act came into force in 1974 and there is documentary evidence of the provision of a first aid service from the 1950s and safety campaigns from the 1960s, demonstrating a transition in attitudes to health and safety in dock work. However, one in seven workers had suffered a significant (reportable) personal injury at work and there were also stories of extra pay being agreed for tasks thought to be hazardous (i.e. the payment of ‘danger money’).

There were stories illustrating the extent to which members of this community looked after one another. From the 1960s, there was welfare fundraising in buckets, on pay day, with a more formal system of welfare funding for dockers and their families from 1971. There were some humorous stories, such as that of a dock workers’ day trip to Rhyl, during which one man was found to be the worse for drink, and was looked after and taken home on the coach. The next morning it was discovered that he had been on holiday in Rhyl with his family and was not part of the dockers’ outing!

Emma concluded by observing that her interviewees typically wanted to emphasise the presence of humour (sometimes dark) and solidarity within their community, and to portray community relations in a positive way; she suggested that the reality may not have been quite so good as it was often portrayed.

Emma’s talk was well received by our audience with a lively Q&A session at the end, after which Margaret Boneham gave a vote of thanks, and we adjourned for the usual tea/coffee, biscuits and chat.

Chris Nelson

Celebrating the 150-year anniversary of The Institute of Continuing Education, Cambridge University

It was a pleasure to join in the recent 150-year celebrations at The Institute of Continuing Education at Madingley Hall, part of Cambridge University. It was here in 1873 that a journey leading to “a system of higher education in the various parts of the country” began. The main proponent of such an initiative was James Stuart, who led the University to carry out a two-year experiment focusing on delivering courses to adults – women and men – of the working and middle classes “who had left school”.

The first extension classes were delivered that same year in Derby, Leicester and Nottingham by tutors who, like Stuart, were fellows of Trinity College. Further societies were formed in London and Oxford over the following years and the model of university-led extension education subsequently spread across the world, enabling life-wide open access for millions of adults at many of the world’s leading higher education establishments. This, of course, included the inhabitants of Southport and Birkdale.

We were invited as a University Extension Society (UES) as Southport is, as far as research has shown us, the sole remaining such organisation. In fact, SUES was recognised by being mentioned in the keynote speech by the Director, Dr Jim Gazzard, prior to the celebratory meal, as was Alf Cobham. Alf was a UES student in Southport who was awarded an honorary MA by Cambridge University in 1923 in recognition of his contribution to the University Extension Society movement. In fact, today, very few universities have even retained departments of continuing education and the levels of adult education provision in society has been drastically cut over recent years.

So, if the flame lit by James Stuart, fellow educationalists and suffragists such as Anne Clough and Josephine Butler, all those years ago remains alight, it is only just. This makes the work of SUES in promoting and providing quality learning for people in the local community all the more important. At this time of celebrating the past, as SUES will do with its own 150-year celebrations next year, we might consider how universities and other educational institutions might once again come together with local learning providers to ‘extend’ their services to create further learning opportunities for those most in need in a way that would be worth celebrating again in the future.

Alan Potter (Chairman) and Peter Firth (Treasurer)

Cash for Coronets

In April this year I attended an Arts Society lecture entitled Cash for Coronets. The lecturer, Mark Meredith, stated that between 1870 and 1914 many American heiresses had exchanged their ‘new dollars’ for European titles, becoming known as the “American Dollar Princesses”.

He stated that by 1914 American heiresses made up a total of 12% of the British aristocracy with 42 being Princesses, 60 married to peers and 40 married to sons of peers. During the lecture he gave several famous examples: Jennie Jerome who married Randolph Spencer Churchill in 1874, Lilian Warner Price who married George Charles Spencer Churchill 8th Duke of Marlborough in 1888, Mary Victoria Leiter who married Lord Curzon, Viceroy of India, in 1895, Consuelo Vanderbilt who became Duchess of Marlborough in 1895 and Kathleen ‘Kick’ Kennedy who married William Cavendish, Marquis of Hartington, who would have become the 11th Duke of Devonshire if he had not been killed in action in the Second World War.

The lecture prompted me to investigate how the number of American heiresses crossing the Atlantic changed over time, and also to see whether any of our local gentry families took American wives.

The Scale of the Phenomenon

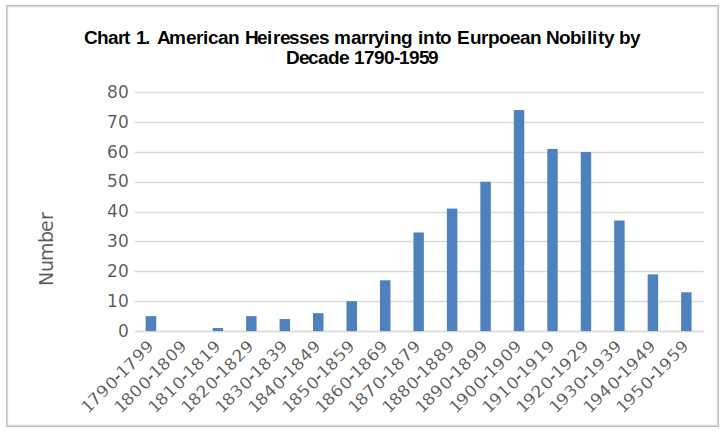

Thanks to the internet I have been able to compile chart 1 below. This shows the number of American heiresses marrying into European nobility, by decade, from 1790, in the reign of George III and only 7 years after the end of the American War of Independence, until 1959, shortly after the start of the reign of Elizabeth II.

As the chart shows, the number of marriages peaked in the decade preceding WW1. The data for individual years shows, quite surprisingly I think, that even during WW1 there were 26 such marriages.

Chart 2 shows which rank of the aristocracy the heiresses initially entered, although it should be noted several went on to make 2nd marriages higher up the aristocracy. The most common marriages were those to a Count.

Local Families

Before starting the research, I already knew that two of Charles Scarisbrick’s grandsons had married Americans but I was unaware of any others. Thanks to Ancestry, I was able to discount any such marriages for the Fleetwood Heskeths of Meols Hall, the Weld Blundells of Ince Blundell, the Townleys of Townley, the Watts of Speke, the Flowers of Arley and the Tattons of Astley. The son of Frederick Stanley, 16th Earl of Derby, married a Canadian – but that strictly doesn’t count! However, I was able to find 6 such marriages, albeit one is only connected with the area because his grandfather was Charles Scarisbrick, which are detailed below.

Scarisbrick

Sir Thomas Talbot Leyland Scarisbrick, grandson of Charles Scarisbrick (1801-1860) and his cousin Sir Herbert Naylor Leyland, also a grandson of Charles via his daughter Mary Ann, married American sisters Josephine (1895) and Jane ‘Jeannie’ Wilson Chamberlain (1889).

The girls, who were brought up in Ohio, were the children of William Selah Chamberlain and his wife Mary. The family’s fortune was due the girls’ great uncle Selah Chamberlain, who was a well-known builder of canals, railways and bridges in the United States. Both couples were part of the Prince of Wales’s set, and ‘for more than a season Jeannie was regarded as the most beautiful woman in London’.

Rufford

Sir Thomas George Fermor-Hesketh, 7th Baronet (1848-1924), was a British baronet and soldier. In January 1879 he started a world cruise in his newly constructed steam yacht Lancashire Witch but it was interrupted by the Anglo-Zulu war. After the war Sir Thomas continued his world cruise and in 1880 was instrumental in the attempted rescue of a number of citizens of San Francisco off the coast of Mexico. In recognition of this, he was honoured in a party given by the city.

(Emile Wauters 1895)

While in San Francisco, Sir Thomas came to the attention of the San Francisco heiress Florence Emily Sharon (1858–1924). Florence was the daughter of US Senator William Sharon, who had made an enormous fortune in the gold, silver, banking and hotel business in California and Nevada. He was first US Senator from Nevada and the wealthiest man in the state. The two were married on 22nd December 1880.

Their son Thomas Fermor-Hesketh, 1st Baron Hesketh (1881–1944) married Florence Louise Breckinridge at the British Embassy Church in Paris in 1909. She was the daughter of John Witherspoon Breckinridge. Her paternal grandfather was General John C. Breckinridge, the former Vice-President of the United States (1857-1861). Her maternal grandfather was Lloyd Tevis the President of Wells Fargo Bank.

Croxteth

Hugh William Osbert Molyneux, 7th Earl of Sefton (1898 – 1972) was the last Earl of Sefton and his family seats were at Croxteth Hall and Abbeystead House in Lancashire. In 1941, he married Josephine Gwynne Armstrong (1903–1980), daughter of George Armstrong of Virginia. He was a life-long friend of the Duke of Windsor, to whom he had been a Lord-in- waiting when he was briefly King in 1936. His new wife was a good friend of Wallace Simpson, the Duchess of Windsor. Unfortunately, I haven’t so far been able to discover Josephine’s family background.

Lytham

Henry Talbot de Vere Clifton (1907–1979) was an eccentric, British aristocrat, poet, race horse owner, art collector and film producer. He spent some time in Hollywood during the early 1930s and, in the mid-1930s, produced films in Britain. In the 1930s and 40s he had three books of poetry published.

He was the son of John Talbot Clifton, squire of Lytham Hall, who had extensive estates and property in England and Scotland, which Henry inherited in his father’s death.

In 1937 he married Lilian Lowell Griswold. She was part of the American political family from Connecticut and New York, although the family were originally from England. The family’s fortune came from 19th century iron and steel industry and through the import of sugar, rum and tea.

The couple divorced in 1943 due to Henry’s affairs. Henry was a gambler and squandered his family wealth of several million pounds, including Lytham Hall which had belonged to the Cliftons since 1606.

Summary

Between the late 19th century and WW2, a flood of “Dollar Princesses” flocked to England. In return for a coveted title, they offered much needed wealth to an English aristocracy short of cash due to poor returns on agricultural land, in part due to the US cultivating grain on its prairies.

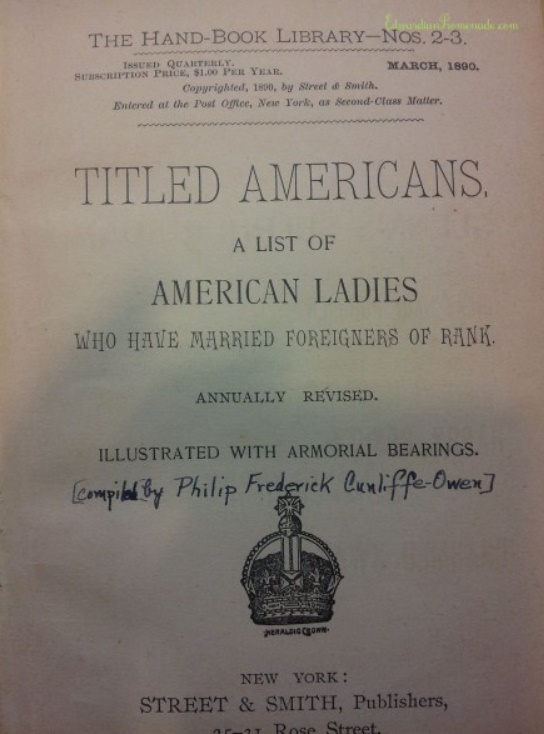

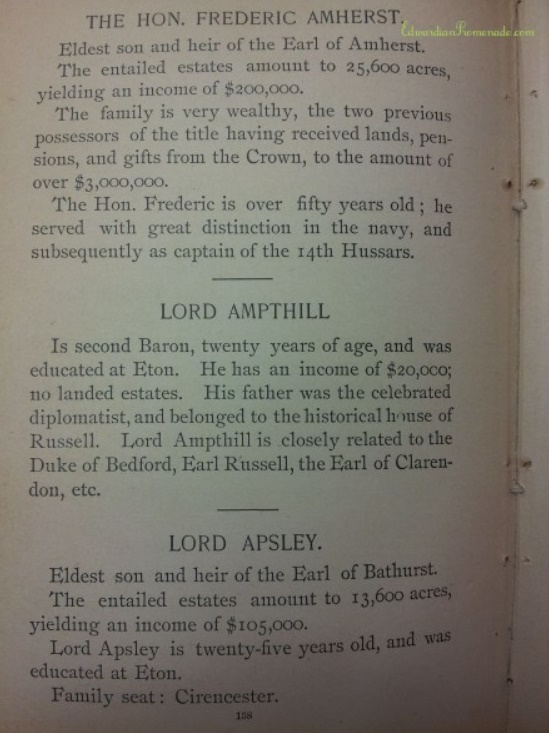

There was even a publication to help them. Titled Americans not only listed the women who had successfully married into the aristocracy, but also listed unmarried men, their titles and reputed fortunes. So each season, American girls, armed with this knowledge, and with introductions from wealthy friends descended on London for the season – to catch their man!

Our local examples are typical. For those whose backgrounds I have been able to determine, their money is ‘new money’ made through trade, banking, industry or politics, and for three the ‘Royal Connection’ via Edward Prince of Wales, later Edward VII, and then to the Duke of Windsor, was important. It seems that, by making their new dollars available, it was easier for many ‘new money families’ to enter the English aristocracy than to break into North American High Society which was ruled over by the Astors at this time.

The trend slowed, in part due to the decline in the number of European aristocratic families and also due to the fact that when the American economy was all but controlled by self-made men, high society could not continue to snub them or their daughters.

Traces of the trend can even be found in our Royal Family. In 1880, stock and railway heiress Frances Ellen Work married the future Baron Fermoy. Like many ‘Dollar Princess’ matches, it was an unhappy one, and the couple divorced in 1891. A mere baron might sound far from the throne, but not really: just over a century after Work traded her money to the aristocracy, her great-granddaughter Diana became the Princess of Wales.

Mary Ormsby

Contacts

Chair: Alan Potter

alanspotter@hotmail.com

07713 428670

Secretary: Roger Mitchell

rg.mitchell@btinternet.com

01695 423594 (Texts preferred to calls)

Membership Secretary: Rob Firth

suesmembers74@gmail.com

01704 535914

Forum Editor: Chris Nelson

chris@niddart.co.uk

07960 117719

Facebook: facebook.com/groups/southportues

See our archive for previous editions of the SUES Forum!