Introduction

This edition of Forum contains three articles and a quiz, all of which include saints of some sort or another. Even though the contents may not qualify as saintly, they can certainly be described as sainted.

Christine Vasey contributes a seasonably appropriate piece on St Valentine’s Day. Mary Ormsby and Roger Mitchell have collaborated on a historical piece that looks at the Popish Plot of 1678 – one of the best examples ever of Fake News. We look at it through the lives of two catholic priests from Lancashire and you may not be astonished to find that both of them made use of the name ‘Scarisbrick’. In what is a spin off from his current course on the American West, Roger Mitchell introduces us to a Latter-Day Saint, William Clayton, who was born in Penwortham but died in Salt Lake City. The final item is another quiz from Mary Ormsby. The format is similar to last month but, of course, the questions (and answers) are entirely new.

Looking ahead to March, we have two Friday afternoon meetings.

The Ecology and Conservation of River Birds

Dr Stuart Sharp, Lancaster University

All Saints’ Church Hall, Friday 3rd March 2023, 2:30pm

Stuart is an animal ecologist working principally with wild populations of birds and mammals to address questions about the interface between animal behaviour, population, ecology and conservation. His current research focuses on the impact of environmental quality and change on the ecology, life history and behaviour of dippers (Cinclus cinclus) and other river birds.

Stuart is also John Sharp’s nephew and his lecture will give us the opportunity to remember John and all that he did for SUES.

Hospice: ‘No Thanks or Yes Please’

Dr Karen Groves, Former Medical and Education Director at Queenscourt Hospice

All Saints’ Church Hall, Friday 31st March 2023, 2:30pm

Dr Karen Groves, who started out life as a local GP, was a founder member of Queenscourt Hospice and was its Medical & Education Director and a local NHS Consultant in Palliative Medicine until semi-retirement in March 2022. She describes her talk as follows:

An individual’s visceral reaction to the mention of hospice is dependent upon their imagined or experiential perception of what a hospice is and what it does. Where has that come from? This talk will be a whistle stop tour of the story of the hospice and palliative care movement nationally, locally and internationally, delving into the past, considering the present and looking to the future. (It inevitably carries an emotional health warning!)

Free refreshments will be served at the end of both meetings and the Committee very much hope that you will be able to attend.

Roger Mitchell

St. Valentine’s Day – February 14th

Was St. Valentine a real person? He was, indeed, and we have quite a lot of information about him. He lived in Rome in the 3rd century AD. He converted to Christianity and became a priest and martyr. There were several St Valentines in the early church but he is the only one we remember. He was arrested for protecting persecuted Christians and beheaded. His relics, scattered all over Christian Europe, became places of pilgrimage and a fragment of him can still be found today in Dublin.

The custom of sending lovers’ greetings on his feast day of February 14th has nothing whatsoever to do with him and it was not until the Middle Ages that he became the patron saint of lovers adding to his existing portfolio of asthmatics, epileptics and beekeepers. The link between St. Valentine and romance is tenuous, to say the least. The genesis of St. Valentine’s Day just might be connected to the ancient Roman festival of Lupecalia held on February 15th in honour of Lupercus, a relative of the god, Pan, who protected livestock from wolves. Antiquarian scholars, in the 18th century, whose classical learning was rather flaky in this respect, noted the date of the Luperclia and turned it into a springtime fertility festival and a time for choosing partners.

Definite records of Valentine’s Day can be found in England from the Middle Ages long before the Lupicalia connection was hypothesised. We need to go back to Chaucer and his long poem, ’The Parlement of Foules’ (c.1381) which tells how the birds choose their mates on St. Valentine’s Day every year. ‘For this was on Seynt Volantynys day whan every bird comyth there to chese his make’ (mate). Other poets of this era, including Chaucer’s friend, John Gower, used the same theme which suggests that these writers were working within an established tradition. A link was thus created between springtime and romance but only of the avian variety. The first poet, that we know of, who linked human beings and love to St. Valentine’s Day was John Lydgate, c. 1440, in his poem ‘A Valentine that Excelleth All’. Very much in the Courtly Love tradition, he wrote:

Saint Valentine of custom year by year

Men have an usance (usage) in this region

To look and search on Cupid’s calendar

And choose their choice by great affection

Such as been pricked by Cupid’s motion

Taking their choice as their lot doth fall

But I love one which excelleth all.

By the time of Shakespeare, Ben Jonson, John Donne and Robert Herrick, the connection between St. Valentine, the early Christian martyr, and young love had become commonplace, especially the widespread belief that getting paired up on St Valentine’s Day was a genuine prediction of true romance.

In the 17th century, Samuel Pepys reveals in his diary that looking for true love on February 14th had more or less become a parlour game. He describes Valentine parties where all the assembled company, married and single, had their names written on pieces of paper drawn out at random and then paired up to play at being lovers, exchanging compliments and small gifts. Another romantic tradition was that the first person you saw on the morning of February 15 was the one for you. Pepys records, mocking her credulity, that his wife, Elizabeth, refused to leave her bedchamber one February 15th because there were workmen in the house.

Valentine cards did not appear until the early 19th century. They were popular with all social levels and some were very expensive indeed, printed on embossed card and decorated with real silk, lace, feathers and even gold leaf. Cards like these have become much sought-after by collectors. All cards had a space for a hand-written message, usually anonymous, or a poem. If inspiration failed, the lovesick could purchase little books of suitable rhymes. However, the space on cards for messages opened the doors to ribald remarks and vulgar parodies. Warning! Not for the easily offended!

I love you a lot. I love you almighty.

I wish my pyjamas were next to your nightie.

Now don’t go blushing. Now don’t go red.

I mean on the clothesline and not in bed!

Such gratuitous smuttiness led, by the end of the century, to a sharp decline in the sales of Valentine cards. In 1894, The Graphic stated, ‘St Valentine’s Day attracts very little attention nowadays but across the Atlantic, the saint is still honoured.’ It is America that we have to thank for the major revival of St Valentine’s fortunes which occurred at the end of World War 2 much to the delight of card manufacturers, florists, chocolatiers, restaurateurs and purveyors of sexy underwear. There were other St. Valentine’s Day traditions, based mainly in rural areas, which survived until relatively recent times. ‘Valentining’ consisted of groups of village children going from house to house on the morning of Valentine’s Day singing a Valentine song and receiving pennies and sweets in return.

Good morrow Valentine! First, it’s yours and then it’s mine.

A Valentine song from Northamptonshire

So please give me a Valentine. Morrow, morrow Valentine.

The custom of procuring a dream of your future husband on St. Valentine’s Eve, seemingly an exclusively female activity, may still exist. I know it doesn’t work because I tried it myself when I was about 13 and nothing happened. This is what you do. Take two bay leaves sprinkled with rosewater and place them under your pillow. Go to bed in a clean nightgown turned inside out (this is probably where I went wrong!) and softly say “Good Valentine, be good to me. In dreams let me my true love see.”

Finally, let’s return to Valentine cards and the people who send them.

The Traditionalist. Roses are Red etc.

I can’t believe I found you

But we are meant to be.

I am always there for you

And you are there for me.

The Sardonic Cynic. Don’t cry! He loves you really!

When I look at you, my heart races.

My blood pressure rises. My palms go all sweaty.

It Is so intense I feel I’m going to faint!

Oh, hang on! That’s my energy bill!

Oozing with Tweeness. Don’t go public with these!

Gumdrop loves his Twinky Poo to pieces.

Flopsy Mopsy mad about her Ribbly Rabbit.

Betty Boo can’t get enough of Silly Boy Billy.

Happy Valentine’s Day!

Christine Vasey

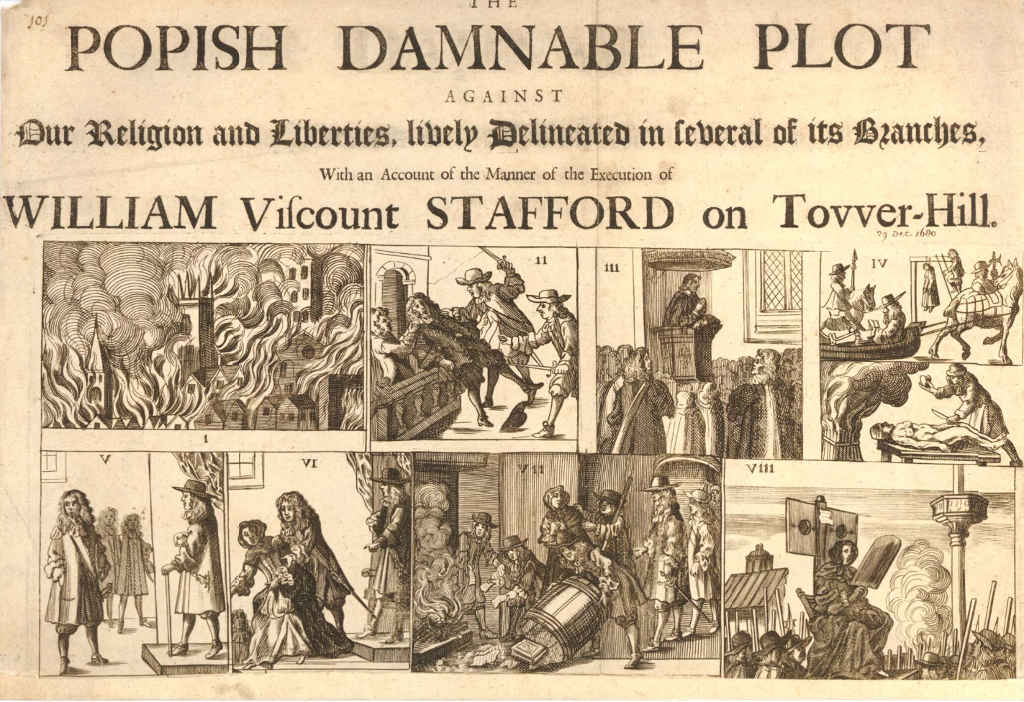

Two Catholic Priests from Lancashire and the Popish Plot of 1678

This piece is a collaboration between Mary Ormsby and Roger Mitchell. With her encyclopaedic knowledge of all things Scarisbrickian, Mary has researched the two local priests at the centre of this story and Roger has tried to link them to events in the wider world from almost three and a half centuries ago. There are modern day comparisons to be made as well, because the Popish Plot must be one of the very best examples of ‘fake news’ and its dangers.

Let’s start with our priests. The elder of the two, whom Mary describes as ‘Mr Scarisbrick’ was not really a Scarisbrick at all. He was John Plessington, born in 1637 to the old catholic family of Plessington at Dimples Hall near Garstang. His early education was given by Father Thomas Whitaker, officially his tutor, but really the family chaplain. Whitaker was arrested and martyred at the stake in 1646 when John was nine.

At that time the Scarisbrick family, at Scarisbrick Hall, a place well off the beaten track and public gaze, ran a secret school under the guidance of a “Mr Palmer” (a Jesuit priest Fr. Ferdinand Poulton). John Plessington lived at Scarisbrick Hall being educated alongside the Scarisbrick boys.

One of those Scarisbrick boys was Edward, who was three years younger than John. Edward and three of his four brothers all became Jesuit priests and John Plessington and Edward Scarisbrick both went on from schooling at Scarisbrick to be educated at the English College and seminary at St Omer in Flanders in the 1650s. As fellow students from similar backgrounds, they were probably close friends during that decade.

Thereafter, their paths diverged. Edward joined the Jesuits in 1659, adopted the surname of Neville and spent the next two decades teaching at St Omer. John continued his education in Spain, was appointed Deacon in Valladolid under the name Scarisbrick and then was ordained priest in Segovia in 1662. He returned to England in April 1663 and spent the next 15 years in Lancashire, Cheshire and North Wales. From c.1669 he was chaplain and tutor to the Massey family at Puddington Hall in South Wirral where he was well loved and respected.

Both men might have lived out their quiet and worthy lives with the only unanswerable question being why, when taking a new name to protect his family, John chose the name Scarisbrick, a choice which surely identified him as a catholic. Perhaps he hoped that with so many Scarisbricks already active, an extra one might go unnoticed. Edward seems to have been more astute in choosing and using the name Neville. There were plenty of respectable protestant Nevilles in Restoration England. Life in St Omer was safe and comfortable and life as a catholic priest in England in the 15 years after Charles II’s restoration was less dangerous than previously. Charles II was personally supportive of toleration and the 1660s was the first decade in more than a hundred years in which no catholic priest was executed for his faith.

The 1670s, however, was an increasingly dangerous decade for Catholics. The Test Act of 1673 required all office holders to reject Catholicism and there was increasing support for the campaign to exclude from the throne the heir presumptive, Charles’ catholic brother, James, Duke of York. Matters took a more dramatic turn in 1678 when Titus Oates, conspirator and perjurer, claimed to have uncovered a Popish Plot and the country entered a period of crisis that changed the lives of both John and Edward.

The most important point to make about the Popish Plot is that there was no such thing. It is a textbook case of Fake News and it retains its relevance today. If you want to learn more in a most entertaining way, then read ‘The Popish Plot’ by John Kenyon. In essence, Oates invented and publicized a plot by Catholics, particularly Jesuits, to murder Charles II and put his brother on the throne. Although Oates had a disreputable past and produced no credible evidence, his allegations were widely believed and the country lurched into hysteria and political crisis. Politicians stoked the flames and the crisis which began in October 1678, peaked in 1679, gradually lost its impetus in 1680 and finally collapsed in 1681.

Hysteria was greatest in London but spread through the whole country. In Cheshire, Plessington was arrested and put on trial in Chester. Even though no connection with any plot could be established, he was found guilty as a catholic priest under an act from the previous century. He was hanged, drawn and quartered at Chester in July 1679 and is now honoured as a saint and one of the 40 English Martyrs. More than 30 innocent individuals, not all of them priests, were executed between 1679 and 1681. The last time that a catholic priest was executed in England for his faith was on the 1st July 1681 when the Irish bishop, Oliver Plunkett was executed at Tyburn.

Edward Scarisbrick was more fortunate, but he seems to have deliberately put himself in the way of danger. As a Jesuit, he was particularly at risk and in 1679, he was named by Titus Oates as a leading plotter. Nevertheless, he returned to Lancashire in 1680 as a missionary and avoided arrest. He appears briefly on the national stage in 1687, during the reign of England’s last catholic King, James II. Edward was appointed a royal preacher and helped establish a new Jesuit College at the Savoy. His sermon on ‘Catholic Loyalty; upon the Subject of Government and Obedience’ was published in 1688, the very year when James was deposed by his son-in-law William of Orange and his daughter Mary. Edward sensibly escaped to France but by 1693, he judged it safe to return to Lancashire where he became chaplain to the Culcheth family. He seems to have lived out his days quietly and died peacefully in 1709.

Late 17th century England was a dangerous place, particularly so for Catholics and especially so for catholic priests. John Plessington (Mr Scarisbrick) was unfortunate in the Popish Plot crisis of 1679 while Edward Scarisbrick was fortunate that, like his master, James II, he was able to escape to France in 1688. Outside times of crisis, however, Catholics were no longer actively persecuted, although they continued to be discriminated against. The last twenty years of Edward’s life were peaceful, but, unlike John, he did not achieve sainthood.

Mary Ormsby and Roger Mitchell

Most of this information comes from the Dictionary of National Biography which has entries for both John Plessington and Edward Scarisbrick.

William Clayton of Penwortham and Salt Lake City

My course on ‘Art and Architecture of the American West’ is now more than halfway through, and as always, I have much enjoyed preparing and delivering it. The problem, of course, is how to fit everything in, particularly when there is so much ground to cover and so many tempting diversions.

What follows is one of these diversions. I am always interested in Lancastrians who left their native county and achieved success and, perhaps, even fame in a very different part of the world. The artists Thomas Cole and Thomas Moran, both born in Bolton, although almost half a century apart, are great names in American art. Butch Cassidy counts as an honorary, if not entirely honourable, Lancastrian because his father was born in Preston. William Clayton is another candidate. We came across him on the course, because he was a member of the first Mormon company to cross from Illinois to Utah and establish what grew into Salt Lake City.

Further research revealed an important and complex man but he was neither artist nor architect and so he did not qualify for inclusion in the course even though he was a musician and composer of hymns, and kept the accounts for building the Mormon Temple at Salt Lake City. However, his life was an interesting one and I promised course members that I would write a short article for Forum to satisfy their and, I hope, your curiosity.

William Clayton was born in Penwortham, near Preston in 1814, and was a member of a well-established local family. His father was a school teacher and William was the eldest of 14 children. He seems to have worked as a clerk and at the age of 23, he married Ruth Moon. In 1837, they came into contact with the first Mormon missionaries to England and were converted. Preston was the centre of English Mormonism and by April 1838, Clayton had been baptised, made a priest and then a high priest. His wife, parents and siblings all converted and began to plan to emigrate to Nauvoo, Illinois where the Mormon church was then based.

The remaining 41 years of his life were spent in the service of the Church. He went to Nauvoo, and served as secretary to Joseph Smith, the founder of the Mormons, and was part of the first company to reach the Great Salt Lake and wrote what proved a very popular guide to the trail which helped many thousands of migrants, Mormons and others, to find their way. Ever the practical man, he had developed and constructed an odometer, an attachment to the wheels of a wagon that counted the revolutions and therefore measured the distance travelled in an accurate way.

In Salt Lake City, he took on an enormous amount of work, serving on committees of all kinds. Mormon sources describe him as ‘a dedicated and industrious saint’. He was treasurer of Zion’s Cooperative Mercantile Institution and of the Deseret Telegraph Company, Recorder of Marks and Brands, Receiver of Weights and Measures and Territorial Auditor. He was a member of the Council of Fifty and Temple Recorder of Revelations. He found time to be a member of the brass band and the opera house orchestra and wrote one of the most popular Mormon Hymns, ‘Come, Come ye Saints’. All told, he seems a strong candidate for inclusion in the pages of Samuel Smiles’ Self Help.

He only returned once to England travelling there as a missionary in 1852. He enjoyed returning to Preston and Penwortham but the visit ended unhappily, when he was accused of drunkenness and immorality. As early as 1833, Joseph Smith had ruled that alcohol should not be drunk, but Clayton did lapse and the charge may be justified. More serious and more complex was the charge of immorality. To his contemporary church leaders in Salt Lake City, he was entirely innocent of this, because plural marriage (polygamy) was allowed and even encouraged. Clayton seems to have needed little encouragement. He was the husband of ten women and father of forty-two children, though four of his wives left him for various reasons. As his Mormon biographer, James Allen, carefully puts it, ‘this clashed with some English sensibilities’.

When he died at age sixty-five, tributes were paid. He was described as follows:

He did not tend to frivolity or mirth but rather to seriousness and earnestness. In the home he was not demonstrative; although he had great love for his home and family and provided well for their comfort. He believed that what was good for him was good for all men, and that the measurement of our lives was based upon our daily conduct towards each other. He believed in perfect equity in the adjustment of the affairs of life. His love for education prompted many sacrifices and he tried hard to give his children the essentials of good schooling. He had a strong will, although a tender conscience. Cowardice had no place in him. Truly he could say, ‘My heart is fixed. I know in whom I trust.’

Obituaries also noted that he left four living widows, thirty-three living children ranging in age from ten to forty-three, and one child on the way. A century and a half after his death, we will inevitably and rightly make judgments on both the man and the society in which he lived. We will recognise the contributions that he made to the Mormon community, applaud his energy and determination, worry about his lapses regarding drink but we will almost certainly condemn his plural marriages, most, but not all, to teenage brides.

The Mormon Church ended polygamy in 1890 but in the eyes of the church those early Saints remain heroic figures like the rulers and prophets of the Old Testament who also had many wives.

There is no statue of William Clayton in Penwortham to share the same fate as that of Edward Colston in Bristol and plural marriages and slave ownership are not entirely comparable, but both raise complex issues. Unacceptable to us, condemned by many contemporaries, they nevertheless remained part of the world in which our predecessors lived. The famous opening words of L.P. Hartley’s novel, ‘The Go Between’, may have been overused but they still deserve our careful consideration. ‘The past is a foreign country. They do things differently there.’

Roger Mitchell

Connections

Answer questions 1-9 normally but bear in mind that all of the answers have something in common.

1. ROYGBIV is a mnemonic for remembering the colours of the rainbow. What does the R stand for in this mnemonic?

2. Melbourne is the capital and most populous city of this Australian state.

3. Who is the Patron Saint of England?

4. What is the name of the new line on the London Underground officially opened in May 2022.

5. Name of the British racing driver who won the F1 World Championship in 1976.

6. Famous film producer and director whose films include: The Birds; North by Northwest and Strangers on a Train.

7. Name of the poet who wrote the line ”I wandered lonely as a cloud”.

8. This 1964 film stars Julie Andrews and includes songs such as “Chim, Chim, Cher-ee” and “A Spoonful of Sugar”.

9. This naturalist, geologist and biologist is best known for his contributions to the science of evolution.

10. What connects all of the answers above?

See after the contacts section for answers…

Contacts

Chair: Alan Potter

alanspotter@hotmail.com

07713 428670

Secretary: Roger Mitchell

rg.mitchell@btinternet.com

01695 423594 (Texts preferred to calls)

Membership Secretary: Rob Firth

suesmembers74@gmail.com

01704 535914

Forum Editor: Chris Nelson

chris@niddart.co.uk

07960 117719

Facebook: facebook.com/groups/southportues

See our archive for previous editions of the SUES Forum!

Answers to Connections Quiz

1. Richard of York gave battle in vain

2. Victoria

3. St George

4. Elizabeth Line

5. James Hunt

6. Alfred Hitchcock

7. William Wordsworth

8. Mary Poppins

9. Charles Darwin

10. All are the names of Kings and Queens of England or Britain.