Introduction

This month we are delighted to present two new contributors. The article by Martin Perry was inspired by Roger’s of last month, while John Turner sees the funny side of medicine, all too necessary in these difficult times. We are sure that you will find both of them entertaining, and we hope that more of you will be encouraged to make contributions. These do not have to be full-length articles, although we welcome those, as short pieces are equally valuable. Roger still hopes for more responses on the question of when England looked its best.

Peter Firth’s course on England under the Norman Kings and Queens is now well under way and is proving of great interest. Seating about 20 people in the meeting room at All Saints seems to be both comfortable and safe, though we are near the maximum that this space can accommodate. If there is anyone interested in the Country House course and has still not booked, we suggest contacting John Sharp fairly soon. The Human Brain course is still some way in the future, but we already have enough reservations to ensure its viability.

As one would expect there has been a lull in membership renewals/applications now the first course has started. We have 53 paid-up members and these will continue to receive this FORUM, either by email or post, but others on the 2019-21 contact list will not after this edition. There have been enquiries about others who might be interested in becoming members. Of course, it is too late to register for the Norman Kings and Queens course, but other benefits are still available. If you know of anyone who might like to have a ‘taste’ of SUES with the prospect of joining, put them in contact with John Sharp.

We are sad to have to report the recent death of Colin Bernhardt, who was a keen attender of our courses. His son reports that they ‘meant a lot to him’, which we are sure refers to the social contact as well as the content.

When Did England Look Its Best? A Local View

(Although the actual name, Southport, was not given until 1792, it is used here to indicate the area from the earliest times.)

This is an impossible question. It depends who you are and where you are. May I change it to a more reasonable question? When did Southport look its best?

At the end of the Ice Age, as the ice retreated, leaving boulders littering the land, and a ghastly blue grey sludge on the surface, it would have looked hellish to our eyes. But as sand blew in from the shoreline, and pockets of soil were created, incipient plant growth would have looked good on a nice day, with the sea beyond.

Early man in Southport would hardly know there was anything or anyone beyond the confines of the sea to the west and the lakes and bogs to the east. The coast was windswept and sand dunes were mobile. Willow, birch and alder were stunted and unsuitable for building. Larger tree trunks were washed up from the forests of the Wirral and beyond. These could be used to build and continually repair the groups of cottages. Clamstaff and daub to the walls, marram grass from the dunes along with reeds from the freshwater lakes on the roofs, completed the job. Dug-out canoes were made from washed up trunks and from ancient bog oak from the edges of the lakes in summer. Things would look pretty good in the spring and early summer; the houses repaired, the women cooking rabbit stew, fish hanging out to dry, children playing, and the men returning from eel hunting on the meres. While the sun shone, Southport looked idyllic. However, the worries of not having enough to eat in the winter, gales battering and destroying the cottages, and raids from neighbouring communities to the north and south, were ever present.

Many long centuries passed until news reached Southport that Roman soldiers were established in Wigan, the Wirral and Chester; and to the North. Southport was ignored as it was so poor and not easy to get to. Occasional refugees turned up, fleeing from the Roman armies, and even the odd dark-skinned stranger who had fled camp life and hoped for something better. These incomers married the local girls. The Romans built a causeway across the bogs and lakes, using hazel brushwood, and Southport became less isolated. Southport had more contact with the world beyond, with Crosby and Liverpool to the south, accessible along the shoreline, and Ormskirk and Wigan to the east, via the Roman causeway. A delight on a sunny day in May, to ride on the road over the mere, on the way to market in Halsall or Ormskirk.

Viking invaders hit the Southport folk suddenly as boats of warriors landed and burned the cottages, and women and children were no longer safe. The local inhabitants were unable to resist this invasion, and all evidence and memory of the past was destroyed. The only hope the people felt was in the church, set up in North Meols, two miles north of the little settlement along the shore in Southport. Not only Viking raids caused instability, but warring tribes of Saxons to the south and east, Picts and Scots to the north, and Celts from Ireland and Wales, increased the fear of raids and made Southport a place of continual change and upheaval. Even on a sunny May morning, Southport did not seem a pretty place to be.

Let us move on to 1066 when William of Normandy landed at Pevensey on the Sussex coast. Southport folk knew nothing of this until they heard that large areas of land had been given to William’s cronies. They heard that the new owners spoke Norman French, and were demanding money and tithes from the villagers. To the east, they were told, that any resistance to the Norman occupiers, had been met with razing whole villages to the ground and slaughtering the inhabitants. As Southport folk were so poor, the conquerors ignored them for a while, but fear for the future made Southport an uneasy place to be. Cottage repairs were neglected as there seemed little point in rethatching if the Normans came to burn Southport as they had to other villages to the east.

Rabbit breeding in the dunes, growing a few crops, fishing in the sea, and eel catching in the meres, continued as before but now regulated as the Lords of the Manors sold licences to the Southport folk. From time-to-time news came of a wider world. Men from Wigan for instance had been to France to fight for the English cause, and even to lands beyond the Mediterranean Sea. It was said that young men went and did not return until they were old. Rumours came and went of terrible plagues that wiped out whole villages, but the sturdy Southport folk were little affected. Although living was hard, particularly through long winters, and life was short, the little settlement was a happy one. Decades ticked by thus, and centuries passed, and nothing happened in Southport. It all looked much as it always had until…

Posters and fliers appeared offering young men unheard of wages to help dig canals in nearby Halsall and Rufford. At the same time even higher rates were offered by Dutch engineers and by the landowners to dig drainage channels and ditches and sluices to try to drain the lakes and bogs. These had isolated Southport from the world beyond, and earlier drainage attempts had failed. Windmills for lifting water had been insufficient, and sea walls had been breached many times in the past. Now the engineers had coal fired steam engines to drain the land, which was known to leave deep black peat, the most fertile growing medium. Slowly prosperity flowed into Southport, and goods from the wider world were available and affordable. Slates from North Wales, stone from quarries round Ormskirk, bricks from the clayfields inland, and glass from St. Helens, appeared in the buildings of the most enterprising inhabitants. These materials had only been seen in the houses of the landowners, and in churches, before now. Everything looked rosy but, and there is always a but, news of the threat of invasion by Boney reached Southport, and prosperity was tempered by apprehension.

When Southport heard that the Battle of Trafalgar had been won in 1805 and better still Napoleon had been finally defeated at Waterloo in 1815, there were great celebrations. Wellington Terrace, which fronted Lord Street and the adjacent Nelson Street were named in memory of these victories. In the early years of the nineteenth century, summer visitors from the manufacturing towns to the east, had sent their families to stay in Southport, for the fresh sea air and even sea bathing. Fishermen’s cottages were adapted to make suitable accommodation for these prosperous holidaymakers. Shops selling fashionable goods as well as everyday produce, were built on the western Lord Street frontage, set back on the higher dunes, as the wide strip down the middle was a dune slack, wet and boggy during high tides, heavy rain, and for most of the winter. During the Spring and Summer seasons it looked lovely, particularly when the visitors were out in their finery, meeting, shopping, and of course attending church. The fly in the ointment was The Old Duke, William Sutton. While he had named Southport in 1792 with his cronies in his pub in North Meols, and he should have been the local hero, he now ran a ramshackle hotel named the Dukes Folly. This was just over the River Nile (named after a famous battle with Boney) at the south end of Lord Street. Here rowdiness and drunkeness were frowned upon by the genteel visitors and the worthy traders, shopkeepers, and hotel owners of Lord Street and The Promenade.

Ramshackle Duke’s Folly can be seen in the dunes. Genteel Wellington Terrace is over the river Nile in the distance. Contrast this with the Lord Street shops set on higher dunes out of the wet.

And now take another look at Southport in say 1885. Southport had really prospered. Not only the summer visitors brought wealth to the town, but easy access by railway from north, south, and particularly from the east, brought migrants from the manufacturing towns with plenty of money and aspirations for their families. Fashionable villas sprang up in the best areas, competing in their opulence, and size and design. To serve them, terraces of artisans’ houses were built in the less fashionable areas of town, inland and away from the sea and Lord Street. The fishermen and their families were pushed out. England was prosperous and Southport and adjoining Birkdale were the fashionable places to visit and to live in, in the northwest of the country. Shops, banks, hotels and churches reflected this. Wealth abounded and everyone wanted to see what it looked like. It all looked wonderful, particularly if the visitor was wealthy.

Now the final view of Southport in 1953 and it is September. Southport Flower Show will open to the public in two weeks’ time. It is Saturday afternoon and the sun is shining. Lord Street canopies are newly painted in black and white, and every shop has baskets of flowers hanging outside. Shop windows have special displays of merchandise. Families are out on the wide pavements, all dressed in their best clothes. Municipal open top buses, painted in red and cream livery, are about as are quite a few private motor cars. Hotels and boarding houses are full. Some luxury goods are now in the shops. Rationing of food and clothes is in the past and the austerity of the war years and its aftermath is over. Britain has a new young Queen Elizabeth: Two years ago a Festival was held and the World had come to see the future here. The highest mountain, Everest, had just been climbed with a New Zealander leading the team, and it felt like another victory for Great Britain. Many countries all over the world acknowledged allegiance to the Queen. People saw that everything was improving, and were confident that good times had returned. Southport was in festive mood and looked its best. People all felt the future was bright.

Southport was a microcosm of England at its best on this day in 1953.

Martin Perry

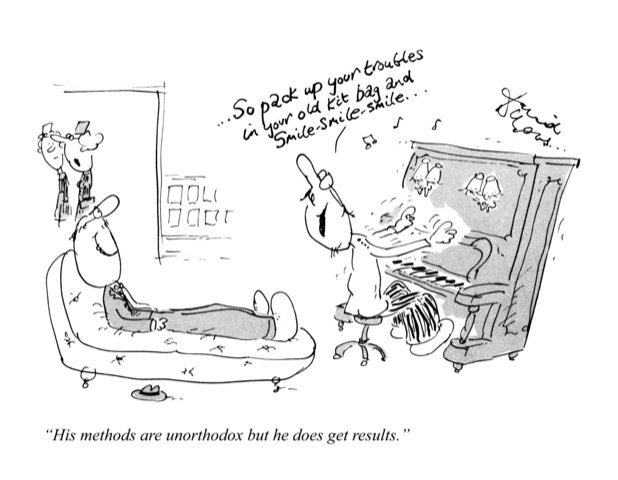

Seniors Smiling Sometimes Seriously

memoir – humour – medicine – social history – the NHS

Man is distinguished from all other creatures by the faculty of laughter

Joseph Addison, 1712

This collection draws on forty years of observations and experience as a consultant physician and the rich variety of characters, colleagues and personalities that I have been privileged to encounter.

Medical interactions reflect the extraordinary range of individual quirks, foibles and mannerisms of professionals and their patients. Most of us receiving medical advice prefer our clinicians to be capable and proficient, yet able to deliver services with a smile. In medical practice, the emotional pendulum can oscillate rapidly between the deadly serious, the deeply moving and the poignant, at times swinging into the irresistibly funny or the frankly comic. Humour comes with plenty of scope for misunderstandings, but for many is a welcome, sometimes inspirational tool for psychological survival, capable of lightening the load and lifting the mood in life’s darker moments.

About the Author

Born in Sheffield, I qualified at St Mary’s Hospital, Imperial College London and held posts in London, Dublin and the Nuffield Department of Medicine, University of Oxford, then consultant physician and later clinical director of Medicine at Aintree University Hospital. Transitioning towards retirement, I acquired an MA History (Chester) and a PGCert Psychology (Liverpool). I am a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians, London, where I interview for the oral history collection.

Early Promise

Aged seventeen and faced with the A-level Zoology practical examination, I sensed the presence of the bespectacled, tweed-suited examiner observing my dissection performance. With a twitch of an eyebrow, he whispered, “did you use an axe?” Rising anxiety only partially allayed by the faintest hint of his suppressed smile. The exercise required demonstrating dexterity with scalpel, surgical scissors and forceps, to display the anatomy of the branchial arches (gills) of a rough-skinned lesser-spotted dogfish. An ugly brute of a specimen, preserved in acrid, sneeze provoking formaldehyde – my least favourite part of the curriculum.

Primitive members of the shark family, dogfish are common in British waters but less valuable and nothing like as tasty as haddock or cod. Often sold in fish and chip shops as the euphemistic, more palatable-sounding rockfish, or more optimistically as ‘rock salmon’.

Royal Marines Can Do Anything

Doreen looked up from her hospital bed with a confident and knowing smile, sitting up to reassure the ward-round team not to worry, as her former Royal Marine brother ‘could do anything’. An ex-wartime Wren she had an unshakeable belief in the capabilities of Her Majesty’s marines.

Short-term memory patchy, with legs refusing to coordinate as once they did, she was slowly and shakily, rehabilitating from pneumonia. The physiotherapy assessment did not sound promising, ‘not safe on stairs and borderline for independent living’. Her discharge was cancelled and replaced by a home visit to assess safety in her more familiar environment.

The front door swung open to reveal a rope terminating in a noose, swaying ominously in the hallway. The senior therapist, pulse rising and mind racing, struggled to make sense of the scene as warning signals from the Caring for the Carers course flashed through her brain. Where was the brother? Stressed relatives do funny things – but surely not?

The former commando and colour sergeant, now eighty-five, retained a sturdy physique and emerged onto the landing wearing an HMS Ark Royalheritage poloshirt. Expertly and nonchalantly, he demonstrated his home-made hoist, rigged with a leather sling, tailored for Doreen’s sizeable torso. Patiently explaining that, as she was “not too good on her legs”, he used a ship’s block and tackle to haul her upstairs.

Baffled alarm melted into smiles of relief as Doreen beamed, looked at her brother admiringly and announced how happy she was to be home.

Passing Through at Park House

Father Gerard O’Keefe had felt increasingly unwell through a busy weekend of masses, baptisms and a long-awaited wedding, that neither he nor the bride wanted to rearrange.

By Monday the irritating dry cough, annoyingly amplified by the microphone clipped to his vestments, had loosened, resulting in sticky green sputum discolouring his newly laundered white handkerchief. Feeling hot and shivery, he was now sweating profusely.

A call from the lab reported a high white cell count, and a look at the chest X-ray revealed an unmistakeable area of bronchopneumonia in the left lung.

After admission to Park House, his temperature continued to rise. At four in the morning, drenched in sweat, he experienced a bed-shaking rigor when the thermometer exceeded 40°C. The delirium peaked in the dead still of the graveyard shift, as a heavy-lidded night nurse sipped tea in the ward kitchen, hoping to stave off an overwhelming urge to close her eyes. Her reverie roused by a voice reverberating through the sleepy silence of the corridor; “Call the Archbishop and tell him I’m dead.”

At eight o’clock the ward bustled with activity as the night shift handed over to the day nurses, breakfast was served and those fasting prepared for theatre. The intravenous antibiotics had worked their magic and Father Gerard’s temperature had fallen almost to normal, even better his mind was clear. Sitting up in bed with tea and buttery toast, as the nurses jokingly teased about the nightmare, he retorted. “Quick, ring the Arch and tell him O’Keefe is back.”

Lexical Gremlins Invade Medical Letters

Unintended humour has long featured in consultant letters to general practitioners. An ill-fated, short-lived managerial exercise, outsourcing dictation from NHS hospitals to faraway typing pools in South Asia, produced a spectacular increase in lexical creativity.

We have identified the Euston Station Tube problem (eustachian tube)

There is a suspicious noodle in the left breast (nodule)

Her persistent horse voice requires laryngoscopy (hoarse)

The patient will be listed for a boloney amputation (below knee)

The polyp looks eminently respectable (resectable)

A fragment of stork remained after uterine polyp resection (stalk)

The helicopter by lorry test proved positive (Helicobacter pylori)

Some super flea bites in the left leg (superficial phlebitis)

Letters from Mental Health Seem Especially Prone to Linguistic Misunderstandings

The patient has two teenage children but no other abnormalities.

His paranoia is quite well controlled. The chip on his left shoulder balances the chip on the right.

This patient has been depressed ever since seeing us in 1991.

Murmuration of Masks

Wellcome Collection London

Earlier generations would have been bemused by the outsized notice displayed on the anti-Covid Perspex shielding reception: ‘This Trust has a zero-tolerance policy towards verbal or other abuse of hospital staff.’ The message hammered home by a graphic, offering offenders the choice of NHS or Police. Its starkness contrasted by a cheery uplifting poster from Rosie Regan of St Julie’s Primary School, featuring a rainbow above ‘We Love our NHS’.

A murmuring hum of hushed voices emanated from behind the masks of the assembled patients. All looked orderly behind their masks, as they waited to be summoned into clinics for Haematology, Chest Medicine and Oncology. The most popular face coverings were blue surgical paper masks, then the solid black or whites, amidst which were some colourful fabrics printed in geometrics or nature themes. Some contained football logos and an occasional entrepreneurial message: Helta Skelta Taxis, and Clare Hair Care. A smattering sported more elaborate masks, some with air filtration devices, over which the extra-vigilant had positioned visors.

Only one was not wearing a mask, its absence explained to the staff as a medical exemption because of panic attacks. Some were far from perfectly positioned with exposed noses, while others slipped them on and off when talking. A teenager, compulsively eager to avert dehydration, lifted hers every few minutes, sipping from a litre bottle of sparkling water. Others made adjustments to accommodate lattes or cappuccinos, from polystyrene containers. One young woman, with a palm-tree-themed, satin designer mask, Doc Marten boots, pink leggings and a vivid mini beach-dress – displaying her impressive tattoos – announced her arrival from a holiday sunspot.

Heads turned and conversation ceased, as the phlebotomist pressed a buzzer then flashed number sixty-six onto the screen. A man briskly stepped forward, but dejectedly returned to his seat after the ‘phlebo’ examined his ticket, turned it the right way up and pointed to number ninety-nine.

Where’s the Doctor?

As doctors were absorbed into the armed forces in World War II, medical staffing in large mental health hospitals, already precariously thin, became stretched to skeletal levels.

Case record entry September 1939

The patient appears to be sinking slowly

Case record entry May 1945

Still afloat

John Turner

Contacts

Chair: Alan Potter

alanspotter@hotmail.com

07713 428670

Secretary: Roger Mitchell

rg.mitchell@btinternet.com

01695 423594 (Texts preferred to calls)

Membership Secretary: Rob Firth

suesmembers74@gmail.com

01704 535914

Forum Editor: Chris Nelson

chris@niddart.co.uk

07960 117719

Facebook: facebook.com/groups/southportues

See our archive for previous editions of the SUES Forum!