Introduction

This is a busy time of year for SUES. Peter’s course on the Crusades continues and at the end of last month, we enjoyed an excellent lecture from Mary that is reported on below. The committee meets twice in November to manage the remainder of the 2022-3 season but also to look further ahead to the future development of SUES. There will be a report on these committee meetings in the December Forum. Our next Friday afternoon meeting will be on Friday 9th December. Our speaker will be local author, Will Daunt, who will tell us about the poet, Gerard Manley Hopkins and his connections with Liverpool and Lydiate. Full details are given below.

John Sharp, who edits Forum and plays a key role as Membership Secretary, has recently returned home after a stay in hospital. The Committee are rallying round to help but if any correspondence goes astray, please contact Alan or Roger. We send John our very best wishes and our gratitude for all that he has done and continues to do to keep the show on the road.

Forthcoming Friday Meeting: Gerard Manley Hopkins

Friday 9th December at 2:30pm, All Saints Church Hall

A Talk by Will Daunt

Gerard Manley Hopkins was sent by the Jesuits to work as a parish priest at St. Francis Xavier’s Church, Liverpool. Ground down by the levels of poverty and disease in the city, he found some comfort in his visits to Rose Hill House, in Lydiate. The Jesuits had strong links with its owners, the Lightbounds, and, for this reason sent priests to say Mass with the family in their private chapel.

Hopkins wrote little in his 20 months in Liverpool. But he did produce two remarkable and remarkably different poems, ‘Felix Randal’ and ‘Spring and Fall’. This talk looks at the background to the writing of these two poems, particularly ‘Spring and Fall’, written after Hopkins had been walking near Lydiate.

Will Daunt is a published poet and reviewer. In 2019 his guide, Gerard Manley Hopkins: the Lydiate Connections was published, with proceeds going towards the charity Hospice Africa.

In 2021, Will’s story about the Lathom Remount railway was included in the anthology, Then and Now: Images of Lathom House.

The Family at Scarisbrick 1860 – 1945

Mary Ormsby’s Talk on Friday 28th October

In a previous talk, Mary guided us through the history of the family and their house until the death of Charles Scarisbrick in 1860. Thanks to her, we have enjoyed summer visits to see Scarisbrick Hall and its estate and we have come to realise what a remarkable house it is. Our expectations were therefore running high and a well-attended gathering wanted to know whether the history of the family would match the architectural drama that the Pugins (father and son) achieved for their Scarisbrick clients. The answer was a resounding yes, because Mary had a remarkable story to tell and she told it with skill and scholarship. Making excellent use of Powerpoint, she also took the opportunity to introduce us to the wide range of archival material that she has been able to collect.

She started in 1860, when, under the requirements of the entail, the Scarisbrick estate passed to Charles’ sister Anne rather than to his three illegitimate children. They had to ‘make do’ with the non-entailed property, which as a result of the development of Southport, produced a generous and increasing income. Anne was thirteen years older than Charles and had been a widow for more than 40 years. Already in her seventies, she wasted no time in commissioning Edward Welby Pugin to complete his father’s work on an even grander scale and in doing her very best to erase her brother’s memory. She had lived much of her life in Paris, moved in the right circles and had a lifelong friendship (or perhaps more) with the sixth Duke of Devonshire, the Bachelor Duke. Her return to Scarisbrick was on a grand scale and Mary used an extract from the Ormskirk Advertiser to describe the celebrations. Over the next decade she spent £85,000 and completed the house.

When she died in 1872, the property passed to her daughter Eliza, who had married into one of the great families of France and, in consequence, held the title of Marchioness of Casteja. For the next 50 years Scarisbrick was unusual in having European rather than British owners. The estate was developed, the Castejas proved good landlords and the house was maintained and used, particularly for autumn shoots. The lifting of the entail meant that when Eliza died, the property was inherited by her husband’s illegitimate son, who had been adopted by Eliza. The First World War brought change to Scarisbrick as to so many English country houses and in 1923, the Castejas sold the property. Remarkably, the purchaser was someone who, unlike the Castejas, was a genuine, if illegitimate, Scarisbrick. Sir Thomas Talbot Leyland Scarisbrick was Charles Scarisbrick’s grandson and an important figure in Southport. He and then his son, Sir Everard Scarisbrick were the last private owners and Sir Everard sold the Hall and the last portions of the estate in 1945.

Mary skilfully led us through this complex story taking us into modern times with Sir Tom travelling the world as well as paying a fine for driving ‘furiously’ along Lord Street. She even found time to sketch in the most recent phase of Scarisbrick’s history as a teacher training college and, from the 1960s through to today, as a school. It was good to hear of the creation of a Trust to ensure the long-term future of the Hall.

Scarisbrick is raising its profile and, with its new Arts Centre under construction, seeking greater community involvement. As an unofficial ambassador for Scarisbrick Hall and for its inhabitants over the centuries, Mary is helping to spread the word. She gave us an afternoon that was both entertaining and informative. By the time that refreshments were served, we all knew a great deal more about what lies beyond the brick wall and entrance lodge on the Southport to Ormskirk road.

Roger Mitchell

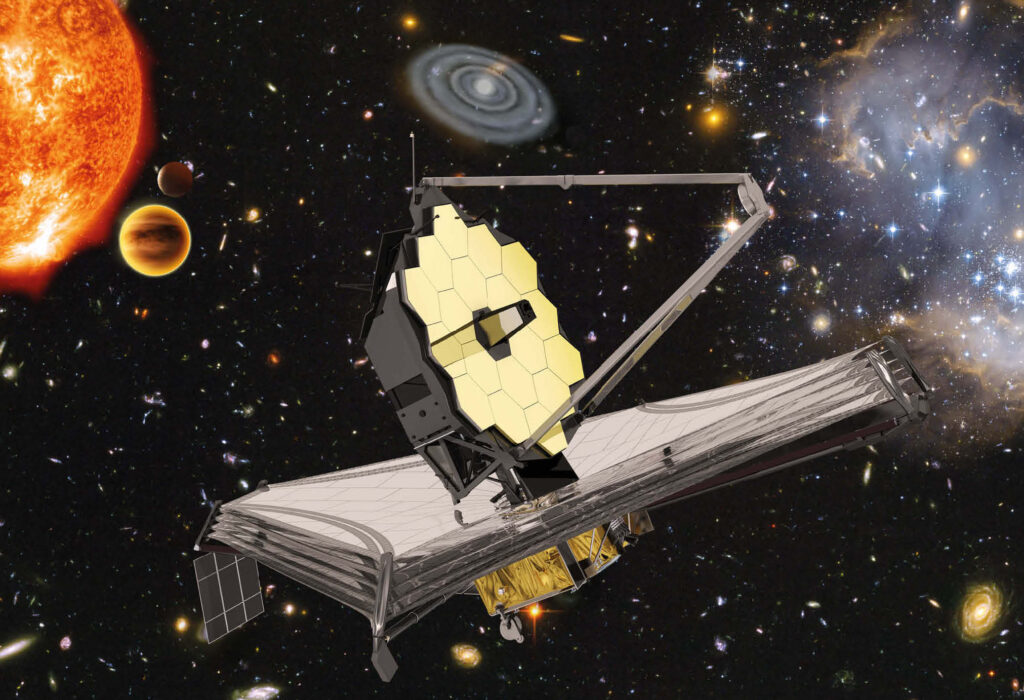

The Wonder of the James Webb Space Telescope

The universe was born in darkness 13.8 billion years ago, and even after the first stars and galaxies blazed into existence a few hundred million years later, these too stayed dark. Their brilliant light, stretched by time and the expanding cosmos, dimmed into the infrared, rendering them, and other clues to our beginnings, inaccessible to every eye and instrument. No longer. At the end of last year, in December 2021, the James Webb Space Telescope, the most powerful space observatory yet built (image below), was launched and now offers a spectacular glimpse of our previously invisible early cosmos after a long journey to get into position.

It was twenty years ago when it was first decided that a new space telescope should be built, multiples of the size of its predecessor, the Hubble Space Telescope, and capable of observing the infra-red Universe. A US-led consortium with Canada and European countries including Ireland, planned a $500 million telescope to launch in 2012. Controversially, the James Webb Space Telescope took nearly another decade to launch and cost 20 times more. James Webb was NASA’s second Administrator who oversaw the Apollo missions to the Moon and single-handedly saved the Viking, Pioneer and Voyager programmes from Lyndon B Johnson’s budget cuts. The telescope, named in his honour, promises to be as enigmatic as the programmess he saved.

The telescope comprises a stunning 6.5m-wide gold mirror (over six times the size of Hubble) and revolutionary heat shields that lower the telescope’s temperature to a staggering seven degrees above absolute zero (-266 oC). The Webb telescope’s primary mirror gives Webb about seven times as much light-gathering capability and thus the ability to see further into the past. Another crucial difference is that Webb is equipped with cameras and other instruments sensitive to infrared, or “heat,” radiation. The expansion of the universe causes the light that would normally be in wavelengths that are visible to be shifted to longer infrared wavelengths that are normally invisible to human eyes.

“We’re one step closer to uncovering the mysteries of the universe. And I can’t wait to see Webb’s first new views of the universe this summer!” NASA Administrator Bill Nelson said in a statement shortly after its launch.

Whether chasing optical and ultraviolet light like Hubble or infrared light like Webb, telescopes can see farther and more clearly when operating above Earth’s distorting atmosphere. That’s why NASA teamed up with the European and Canadian space agencies to get Webb and its mirror, the largest ever launched, into the cosmos. Of course, the Hubble telescope is in low Earth orbit, where astronauts can visit and fix things that have broken or worn out, or install new, more powerful instruments on it. In fact, spacewalking astronauts have performed surgery five times on Hubble. The first operation, in 1993, corrected the telescope’s blurry vision, a flaw introduced during the mirror’s construction on the ground. Those modifications extended its life years beyond the original estimates.

By way of contrast, the James Webb Space Telescope is now situated one million miles from Earth (four times as distant as the moon) peering back in time to early galaxy formation. NASA confirmed the whole operation went as planned but the mirrors on the $10 billion observatory still had to be meticulously aligned, the infrared detectors sufficiently chilled, and the scientific instruments calibrated before observations could begin from June this year. The Webb is expected to operate for well over a decade, maybe two, and is considered the worthy successor to the Hubble Space Telescope.

In fact, the telescope will enable astronomers to peer back further in time than ever before, all the way back to when the first stars and galaxies were forming 13.7 billion years ago. That’s a mere 100 million years from the Big Bang when the universe was created. Besides making stellar observations, Webb will scan the atmospheres of alien worlds for possible signs of life.

The engineering feats involved are simply mind-boggling. The telescope was launched from French Guiana and, after a week and a half, a sunshield as big as a tennis court stretched open on the telescope. The instrument’s gold-coated primary mirror, 21 feet across, unfolded a few days later. The primary mirror has 18 hexagonal segments, each the size of a coffee table, that had to be painstakingly aligned so that they see as one – a task that took three months. Precise thruster firing put the telescope in orbit around the sun at the so-called second Lagrange point, where the gravitational forces of the sun and Earth balance each other. The 7-ton spacecraft will loop-the-loop around that point while also circling the sun. It will always face Earth’s night side to keep cool.

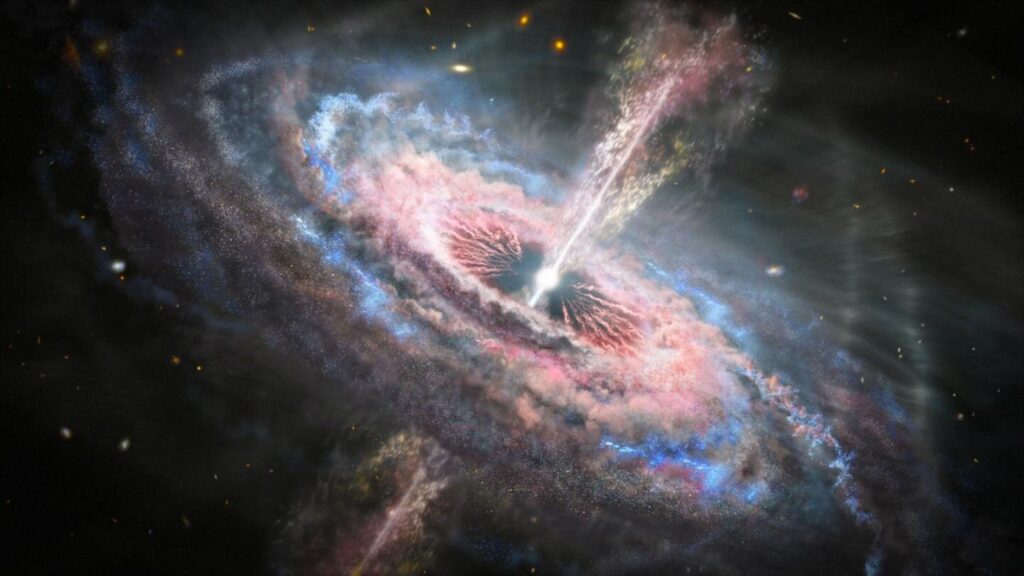

It is worth recalling two great scientific discoveries of the past century. The first is that the Universe is expanding and hence had an origin. The second was a chemical basis for the origin of life on Earth, suggesting that life may be common throughout the Universe. Two iconic images by the Hubble Space Telescope perhaps best exemplify these enigmatic discoveries: Deep Field is an image showing thousands of galaxies over 13 billion light years away that formed shortly after the birth of the Universe (which Hubble determined to be 13.8 billion years old). The Pillars of Creation (image above) are three gargantuan columns of dense gas and dust at the heart of the Eagle Nebula within which thousands of stars and planets are being born now. Through such imagery, Hubble revolutionised our view of the Universe and triggered a paradigm shift in our understanding of our place in the grand scheme of nature.

But as powerful as the Hubble is, it does have limits. Its extraordinary discoveries now point to new questions, on how galaxies first arose, on how precisely stars and planets are born, whether planets orbiting other stars (exo-planets) harbour life, and on the full extent and makeup of our own Solar System. Finding answers to these great unknowns not only demands even more powerful space telescopes, but a new approach to observing the Universe. The challenge with seeing the very first stars and galaxies is that they are by now racing away from us at the far end of the Universe and at near the speed of light. Through what is called doppler shifting, stars that close by would glow in visible light are red shifted to glow in the infra-red part of the spectrum, demanding infra-red (heat) detectors to see them.

It is reasonable to ask, how can we hope to observe star and planet births when they are obscured by the nebulae within which they reside? Once again, infra-red detection is the key. The dynamism of their births generates heat that can penetrate gas and dust, enabling us to observe the moment of their births. If we hope to determine the material makeup of the billions of worldlets currently unseen that are orbiting our Sun, and of the atmospheres of an estimated two trillion planets strewn across our galaxy, which are equally elusive because of their remoteness, we must call upon well-honed Earth-science techniques that monitor our continents and oceans from orbit. Remote sensing identifies the make-up of a far off object by the unique heat-signature that emanates from each material making it up.

As for the first image, Webb got straight to the point by zooming in on four targets including a stellar nursery called the Carina Nebula (above), as well as a galactic cluster comprising some of the very first galaxies to have arisen in time – just a taster to whet the appetite. The James Webb Space Telescope will herald a new era in astronomy not only because of extraordinary images, but because it will illuminate the hidden workings of the Universe that until now we have not been privy to. It is the first instrument to attempt to see the very first stars born at the dawn of time itself; and perhaps, just perhaps, it might glimpse a far-off planet upon which are the tell-tale signs of life. Hang on to your hats, it’s going to be an exciting 15 years!

Alan Potter

In my capacity as temporary editor, I could not resist adding the following short article. Mary Ormsby sent it to me earlier this week and it manages to combine optics and birds. As such it provides both the perfect postscript to Alan’s article on the James Webb Space Telescope and the perfect introduction to our first 2023 lecture, which will be on ornithology and will be given by John Sharp’s nephew, Stuart Sharp from Lancaster University.

Roger Mitchell

Bird-Safe Glazing – Why Do We Need It and How Does It Work?

One of the last projects that I was involved in when I worked at Pilkington was the Research and Development project to develop ‘Bird-Safe Glazing’. A study a few years ago identified that over 1 billion birds die due to colliding with the windows of buildings in North America alone. The problem has become so severe in places where high rise buildings stand on bird migration routes, that the US congress passed a law making the use of a bird safe glazing compulsory in some cases.

Birds fly into windows for two reasons, either because they can see straight through or more often, they fly towards the reflection from the glass surface, thinking the reflected trees etc. are real. A challenge for the project team was to develop a glazing which was visible to birds but invisible to humans.

A literature study identified that birds’ vision is different to that of humans. They have four cones in their eyes and can see into the Ultra Violet, we humans with three cones can only see across the visible spectrum. The study also showed that there is a minimum space between objects that a bird will fly through, think of tree branches.

The Pilkington Group are world leaders in glass coating development and the R&D group developed a coating which reflects light at the wavelength where a bird’s UV vision is optimum. Whilst the coating is invisible to humans, to birds it appears as a bright stripe. The coating is applied in stripes to the outer surface of the glass, so the bird sees the stripes in front of any reflection and knows something is there. Furthermore, the pitch, or space between the stripes, is optimised so that the space appears too small to fly through.

Thanks to clever science and a cross-disciplinary team, buildings can now be glazed in a way which is safer for birds.

Mary Ormsby

Contacts

Chair: Alan Potter

alanspotter@hotmail.com

07713 428670

Secretary: Roger Mitchell

rg.mitchell@btinternet.com

01695 423594 (Texts preferred to calls)

Membership Secretary: Rob Firth

suesmembers74@gmail.com

01704 535914

Forum Editor: Chris Nelson

chris@niddart.co.uk

07960 117719

Facebook: facebook.com/groups/southportues

See our archive for previous editions of the SUES Forum!