Introduction

We wish all SUES members a Happy New Year with hopes that someday soon we will beyond Covid anxieties and restrictions. At the moment, however, we have to take note of official guidance and ‘proceed with caution’. The first session of Roger Mitchell’s course on ‘The Country House in the Twentieth Century’ took place on Monday 10th January. It was well attended, but by using the main hall we were able to ensure that those in the audience, wearing masks, were well spaced out. There was clear evidence that this event was enjoyed by the members who were present, and it augurs well for the rest of the course and the remaining meetings in this academic year.

First of all in this edition we provide the answers to Mary Ormsby’s December quiz. How well did you do? Then there is an article split into two parts, separated by a second article. You will see why when you read the puzzle posed by Roger Mitchell in Part 1 – you are given time to reflect and come to your own conclusions. The second article is an abridged version of an essay written by John Sharp in response to Peter Firth’s course on the Normans. We include this as an illustration of how the learning we all aspire to as part of SUES activities is a continuing process. We have some more brain-teasers available and intend to make them a regular feature.

Still on the subject of puzzles, for some of us the King William Quiz has become a family tradition at Christmas. This fiendishly difficult challenge has been given to the pupils of the Isle of Man school every year for some decades, and more recently it has been provided for a wider audience by The Guardian. The Guardian used to put it online, but they failed to do so this year, though it is possible to find the quiz on a search, as someone has uploaded it. The alternative, of course, is to buy the paper in future! If you have never looked at the King William Quiz, only do so if prepared to subject yourself to torment.

How Well Do You Know Lancashire?

The Answers

1. Vimto

2. Leyland

3. Lancaster

4. M55

5. Spinning Jenny

6. The Peterloo Massacre

7. Eric Morecambe

8. Lytham St Annes

9. George Orwell

10. The Pendle witches

11. 1890s (May 1894)

12. Burnley

13. Whistle Down the Wind

14. The Queen

15. George Formby

16. David Lloyd

17. Black pudding

18. 1912

19. The Clitheroe Kid

20. Stonyhurst College

A Chatsworth Puzzle

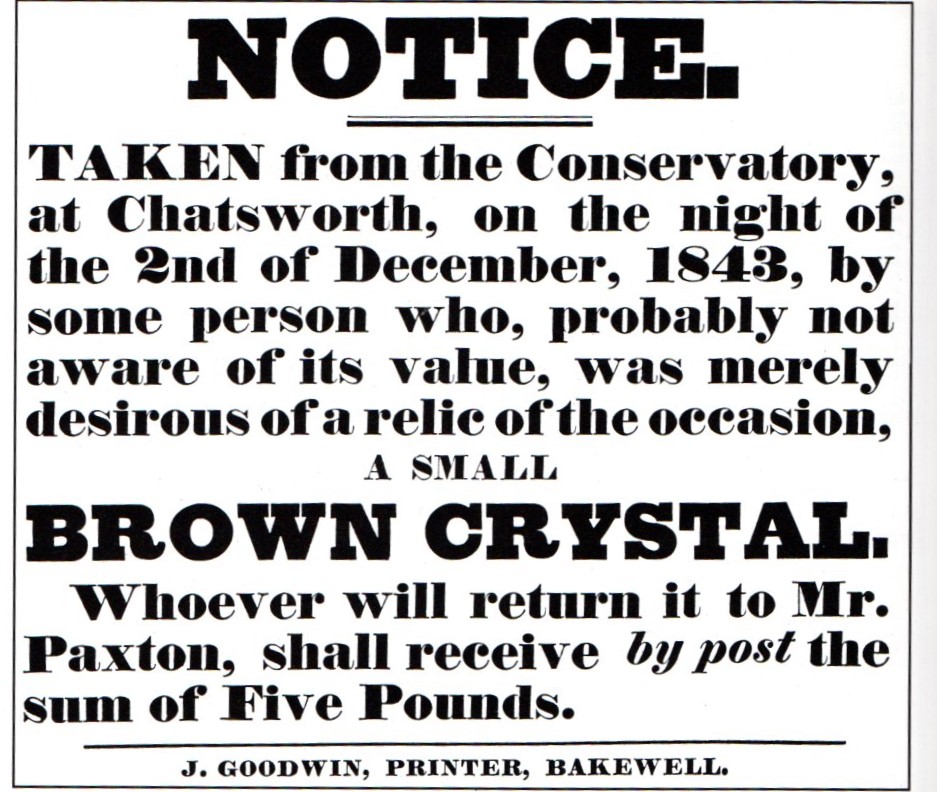

Almost two hundred years ago, in December 1843, this advertisement appeared in the newspapers and on the streets of the area around Chatsworth. It is rare for a single document of no more than 60 words to stimulate so many questions. I will raise some of those questions in this section, ask you how much you can work out and then, at the end of this edition, give you my attempts to find answers.

- Who is Mr Paxton and why does he not give an address? Why will £5 be sent by post?

- Something valuable seems to have been taken but the tone is extremely mild and forgiving. Why?

- What are people doing in a Conservatory, at night and in December? What is the ‘occasion’?

- What could ‘a small brown crystal’ be?

- Was the crystal returned and did anyone claim the reward?

Roger Mitchell

Was the Norman Conquest of England Inevitable?

‘Inevitability’ raises philosophical issues. Is what happens what is bound to happen or is it all just a matter of chance? Is history part of God’s plan – or a confirmation of Karl Marx’s belief in class war? Is it a science? Arnold Toynbee devoted 12 volumes to the study of 27 civilisations (‘Study of History’), in which he saw a predictable pattern of rise and decline, attempting to make a science of History. A more modern view would be that although we can try to explain why things happen, we cannot say that they were bound to happen, and that history does not really repeat itself as a laboratory experiment might be expected to do.

Donald Rumsfeld’s theory of causation was summed up by the phrase ‘stuff happens’. Harold Macmillan put it more elegantly when he described the driving force of political life as ‘events, dear boy, events’. We might call this ‘the contingency theory of history’.

The Norman Conquest is a useful test-case to illustrate these points. If we say that the Norman Conquest was ‘inevitable’ it could have been for one (or both) of two reasons. The first is that Anglo-Saxon England was some kind of ‘failed state’, ripe for conquest; the second, that the Normans were governed by an atavistic and irresistible urge to expand and conquer. There was no stopping them. These two possibilities will be examined before we turn to the role of chance, accident or contingency.

In reality Anglo-Saxon England cannot have looked much like a ‘failed state’ to contemporaries. It had well-established structures of law and administration, and the economy was in reasonable shape. It also had an established culture, to be seen particularly in poetic and historical writings. If it had weaknesses, they were its internal divisions, which had led to many conflicts over the centuries; and the uncertainty of succession to the throne. In the first centuries after the original invasions the many separate kingdoms gradually consolidated into three major ones, each of which was dominant for a time: Northumbria, Mercia and Wessex. Significantly, powerful kings sometimes called themselves ‘Bretwalda’, which is actually referring to Britain rather than England, but it does imply the idea of a unified state. Then, towards the end of the eighth century came the Vikings, first as raiders then as settlers. In trying to limit the power and influence of the Vikings, King Alfred and his successors created and preserved the idea of an Anglo-Saxon state.

It is important to distinguish between the Vikings (usually called Danes, though their origins were more diverse) who settled in the Eastern parts of the country and the continuing invasions from outside. The process of assimilation means that the former were in a sense anglicised. Their language, not too different from English, merged with it to give a linguistic unity. A similar process occurred with the legal systems. However, we are talking of a time when the state was identified with a lord rather with a nation.

While it would be misleading to think of Anglo-Saxon England as a weak or divided state, it cannot be forgotten that the Viking threat continued beyond raids and settlements to something more like dynastic politics. The reign of the ineffective Ethelred (978-1013, 1014-16) encompassed his defeat at the Battle of Maldon by King Sweyn I of Denmark, the payment of substantial Danegeld and the ultimate succession of Sweyn to the English throne and Ethelred’s exile in Normandy. Sweyn’s reign was followed (after the brief reign of Ethelred’s son, Edmund Ironside) by his son Canute (1016-35). The long reign of Canute is in itself a testament to the assimilation referred to earlier. He was largely successful in preserving the peace and maintaining the independence of the realm. He also accepted and implemented traditional Anglo-Saxon law and administration. This illustrates that the succession of Danish monarch was perfectly possible and that was England might have developed as part of a Scandinavian empire.

Canute was followed by two of his sons Harold Harefoot and Hardicanute, but in 1042 Ethelred’s son, later know as Edward the Confessor, came out of exile and resumed English kingship. Edward reigned for over twenty years, and as he was married it must have been assumed in the first part of his reign at least, that in due course he would produce an heir. When this eventuality became increasingly less likely, the succession likewise became uncertain. We must remember that this was a time of transition, between kingship being awarded to the best person for the job and the notion of hereditary succession based on primogeniture. The best claimant to be King after Edward, if we take blood ties, was undoubtedly Ethrelred’s grandson, Edgar Atheling, but he was only a boy (we do not know exactly how old) and had spent much of his life abroad. There was a perfunctory attempt to make him King after the death of Harold II, but this collapsed in the face of a confident William. One could argue that King Sweyn II of Denmark had the next best claim; he was Canute’s nephew and was born in England. He failed to make made any immediate attempt to assert his claim, although in 1069 he did invade England with Edgar Atheling. He captured York, but it was too late to shake William’s grip on the country and he was easily bought off. The three who did most to stake an immediate claim had little justification in blood ties: Harold Godwinson was Edward’s brother-in-law, William of Normandy a distant cousin (and illegitimate by birth), and Harold Hardrada’s only basis was that he was King of Norway. Was it, therefore, inevitable in this uncertainty that William would conquer and become King? Hardly, as Harold Godwinson was the man on the spot and had shown himself to be competent. The chances were that he would succeed without opposition, unless of course there was something in the Norman character that made aggression inevitable.

The Normans were ‘Northmen’, that is to say in origin Vikings. The so-called ‘Viking Age’ began round about 800 CE and lasted for 300 years. They came from Denmark, Sweden and Norway and in their seafaring enterprises spread all over Europe and across the Northern waters as far as the New World. They marauded, they raided, they traded and they settled. They occupied an area of Northern France, which became the Duchy of Normandy; they conquered Sicily as well as England; they were to be found in what was become Russia, the Byzantine Empire, the Iberian penindula, North Africa and the Levant; they took part in the Crusades. But these warriors were also adaptable. When they settled anywhere they quickly abandoned paganism and became Christians, and they usually became assimilated into the culture of their new found homes. The Duchy of Normandy was established in 911; by 1066 the Northmen were French speakers.

Although the Normans had in their ancestry an apparently restless and irresistible force, that ancestry was sufficiently distant when William became Duke. An attack on England was by no means a likelihood. A closer look at the career of William the Conqueror suggests that such a project was not in his mind from the start. The early part of his life was spent establishing his claim to the duchy, a claim weakened because of his illegitimacy. The next part saw him concentrating on the interests of Normandy as part of France. His key concerns were in his relations with his overlord, the King of France, and in his dealings with neighbouring lords, also vassals of that King, looking always to expand and strengthen his Duchy. He spent much time promoting the cause of the Church. The crown of England, when it became a possibility, offered an opportunity, an opportunity to achieve something far-reaching, but not something he had worked towards as a strategy.

If Anglo-Saxon England was not really a weak state, ripe for conquest, and one that had managed to sort out royal succession in times of dispute, and if William was not driven by a driving urge to expand overseas, we are left with the contingencies. The Norman Conquest of England came by chance, and there were several occasions when events might easily have turned out differently. The first of these is the childlessness of Edward the Confessor and then his presumed decision to make William his heir. It may be that this put in William’s mind something that he would not necessarily have otherwise considered. Then, there is William’s rescue of Harold Godwinson, who fortuitously fell into the hands of pirates. Harold’s oath to support William’s claim was obviously made under duress and therefore of doubtful validity, but it was equally obviously taken seriously by William. When Edward the Confessor died, Harold was able to win quickly acceptance as King, though this was on practical rather than any other grounds, and William saw the chance of challenging this succession, particularly as there was significant opposition to Harold, even from his own brother, Tostig. Finally, there was the invasion of Harold Hardrada and the Norwegian forces. At the very least this was a disruptive event, likely to cause a chaos in which the most determined and cunning might win out.

Although these contingencies helped William’s cause, it is not to be assumed that he had simply acted on the spur of the moment. The preparation of a substantial fleet to carry his troops across the Channel is evidence that he had made some preparations for this eventuality. The contingency argument is simply that a number of events, which could easily have turned out differently, favoured him.

Finally, we come to the events of 1066 itself. Harold Godwinson, King Harold II, was successful in defeating the Norwegians in two battles, the second of which was at Stamford Bridge, but victory comes at the price of the loss of some men and the exhaustion of others. However, the news of William’s invasion meant that Harold set off immediately on the journey of several days to the South. Again, it is interesting to speculate on contingencies. What if Harold of Norway had been successful at Stamford Bridge and what if Harold of England had delayed somewhat to restore his forces before moving south? What if Sweyn of Denmark had acted in 1066 as he did in 1069? There were no foregone conclusions. Furthermore Harold might still have won at Hastings, if the shield wall had not broken at a critical moment. The vagaries of battle swung in William’s favour, although it can be admitted that probably did show superior generalship.

This was not, of course, the end of the story. William had to win the support of leading nobles and churchmen, not to mention the Londoners, get himself crowned, and in the following years crush rebellions. He showed remarkable abilities in accomplishing all this, but he was helped by some lack of decisiveness amongst his opponents, particularly the Northern Earls, who at first accepted him and then turned against him. Even Edgar Atheling, the person with the best credentials to be King, came to his side, temporarily at least. Here again, chance was on William’s side. If Edgar had been older, an adult, he could have been a formidable opponent.

There was nothing inevitable about the Norman Conquest. England was not a rotten fruit ready to fall off the tree, the succession could easily have gone another way, William was not innately expansionist and each of the main events of 1066 could easily have turned out differently. But Fortune favours the brave, and William found all the luck was on his side.

John Sharp

A Chatsworth Puzzle Part 2

- Who is Mr Paxton and why does he not give an address? Why will £5 be sent by post?

Mr Paxton is Joseph (later Sir Joseph) Paxton. The son of a farm labourer, he was born in Bedfordshire in 1803 and became Head Gardener at Chatsworth in 1826 at the age of 23. By 1843, he had reorganised the gardens, built the Conservatory, become the trusted friend of the Duke of Devonshire and rebuilt the estate village of Edensor. Before his death in 1865, he constructed the Emperor Fountain at Chatsworth, designed the Crystal Palace and completed major commissions to design gardens, parks and country houses. He had been awarded a knighthood and had become extremely wealthy.

He was popular and universally respected and everybody would have known where he lived – the Gardener’s House at Chatsworth, which had been enlarged to accommodate his growing family and prosperous lifestyle.

Possible claimants might have felt more comfortable if they could claim their reward by post rather than in person.

- What are people doing in a Conservatory, at night and in December? What is the ‘occasion’?

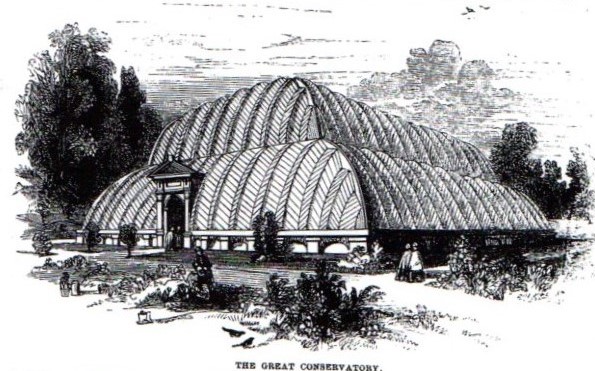

This was no ordinary Conservatory. Sometimes called the great stove, it was a vast glass building, built between 1836 and 1841 with a double-curved framework of laminated wood, measuring 227 by 123 feet and 67 feet high. It cost more than £30,000 and heating was provided by 8 boilers. No glasshouse on this scale had ever been built before and it rapidly became Chatsworth’s greatest attraction.

In December 1843 Queen Victoria and Prince Albert were guests of the 6th Duke of Devonshire. A visit to Chatsworth in December would previously have been unthinkable but they were able to travel by train to Chesterfield station, before proceeding by coach to Chatsworth. The house party included two previous prime ministers, the Duke of Wellington and Lord Melbourne and a future one, Lord Palmerston. The royal party arrived on Friday 1st December after visiting the current Prime Minister, Sir Robert Peel, at Drayton Manor, near Tamworth. They departed for Belvoir Castle at 9am on Monday 4th December. At Chatsworth, there were the usual dinners and a ball for the great and the good of Derbyshire. Victoria and Albert inspected the house, the gardens and the estate. They visited Paxton’s house at the entrance to the gardens and they were shown an enormous pig, described as ‘a porcine magnifico’ that weighed 70 stone and had won the prize at the Derby Show.

The Times reported that ‘multitudes of well-dressed persons thronged the area before and around the mansion and whenever the expectant multitudes obtained a sight of the Queen, they exhibited their loyal feelings in a very appropriate way’.

The highlight was a visit to the Conservatory on Saturday evening. The building was specially illuminated for the occasion, probably using a combination of candles and oil lamps, and was ‘brilliant with myriads of lights’. Her Majesty, we are told, ‘graciously expressed her admiration’ and returned for another visit on the following day by which time ‘every trace of the mechanical arrangements for the splendid illumination had been removed’.

The only thing that marred the event was the disappearance of ‘one small brown crystal’ and Paxton’s carefully worded notice was an attempt to resolve this minor but troubling event.

- Why is the tone so mild and forgiving?

Paxton must have decided that this offered the best hope of success. The visitors had been respectable and well dressed and one assumes that entry to the conservatory itself would have been limited to the most trustworthy and loyal. The size of the reward is unusually high. In the 1840s, £5 would be the equivalent of a month’s wages for a skilled worker.

- What could ‘a small brown crystal’ be?

I can only speculate but we do know that the 6th Duke had inherited a collection of minerals from his mother, Georgiana, and had continued to collect. Could this be a Derbyshire mineral related to blue john? Perhaps, but if it was small and brown, why was it so valuable? It is more likely to have been an opal or topaz, or even a brown diamond. The notice describes it as a crystal rather than a gem and there is no indication that it was an item of jewellery. I would welcome any further suggestions.

- Was the crystal returned and did anyone claim the reward?

This is the big question and I did not expect to be able to provide an answer. However, thanks to the Times Archive, I can tell you that there was a happy ending. In the edition of 19th December 1843, citing a local Derbyshire newspaper, The Times reported as follows.

‘We are truly happy to learn that the piece of crystal abstracted from the Conservatory at Chatsworth has been returned along with a letter bearing the London postmark. This read as follows: Dec 11th 1843 To Mr Paxton – Having observed in a Derbyshire paper that a small brown crystal was missing, the same having come accidentally into my possession, I herewith return it to you, as directed, without wishing for the reward offered.’

The Derbyshire paper was pleased to note that the London postmark meant that the abstraction was not the work of anyone residing in the county and The Times confirmed that the behaviour of visitors was ‘creditable and satisfactory’. ‘Not a plant or even a leaf was removed or destroyed, notwithstanding the great concourse of persons who visited the conservatory or gardens.’

All ended well, but we do not know who took the crystal and whether it was the same person who returned it. Perhaps, the Duke had brought some minerals from his collection to be exhibited in the Conservatory for this special occasion. Perhaps some royal servant had been tempted but, back in London, realised that the publicity made the crystal unsaleable, and therefore to appease a guilty conscience, took something of a risk by returning it, rather than throwing it away.

Roger Mitchell

Contacts

Chair: Alan Potter

alanspotter@hotmail.com

07713 428670

Secretary: Roger Mitchell

rg.mitchell@btinternet.com

01695 423594 (Texts preferred to calls)

Membership Secretary: Rob Firth

suesmembers74@gmail.com

01704 535914

Forum Editor: Chris Nelson

chris@niddart.co.uk

07960 117719

Facebook: facebook.com/groups/southportues

See our archive for previous editions of the SUES Forum!