Introduction

Welcome to edition number 18 of SUES FORUM. As the signs of Spring are here amongst us, perhaps we can assume a feeling of optimism; that the restrictions, which have so much limited our lives and activities, have an end in sight. We are daring to hope that we may be able to arrange face-to-face sessions in June and July. These would include a local lichen walk, an open-air event intended to follow up Alan Potter’s talk earlier in the year, and an event at All Saints, which would include the AGM. We have arranged a speaker for a Zoom talk on 14th May, of which the details are given below.

The first main item in this edition is a short story, which although historical, does have a contemporary relevance. It is also an attempt to broaden the scope of our contributions. It is followed by a further item by Mary Ormsby on the Scarisbrick family. In our October 2020 edition Mary wrote about Charles Scarisbrick and the sources of his wealth. She now takes the story further by examining the lives of his two sons, William and Charles, and of their descendants. A final article in a future edition will deal with his daughter Mary Ann and the descendants of her marriage into the Naylor Leyland family. This is a shortened version of Mary’s original essay. If you would like to see the complete version or learn more about this local family, contact Mary at mormsby@btinternet.com.

The visit to Scarisbrick Hall, which we had to postpone last year is still in our plans for the future. We also have in mind the resumption of multi-session courses for the year 2021-2.

Next Meeting

The Hubble Telescope At 30 Years

This lecture will take place on Friday 14th May at 2.30 pm and will be given by Tony Bell who is a retired Chartered Electrical Engineer and university lecturer. It will be delivered over Zoom and will cover both the historical development of the Hubble Space Telescope and events leading up to its construction. The talk will outline the huge engineering and financial aspects of the project and will be complemented by a NASA video of Hubble’s launch inside the Space Shuttle Discovery. The speaker will then make substantial use of full colour images of the planetary and deep space objects viewed and recorded by the telescope, which illustrate the numerous benefits of this extraordinary achievement. The session will end by considering our future in space and then allowing time for questions.

All those members who have used Zoom with SUES before will automatically be sent a link to attend. Any other members wishing to do so should contact alanspotter@hotmail.com.

Firth’s Law

You’ve all heard of Murphy’s Law, and some of you will know of its coarser variation. The most recent SUES talk introduced us to a similar phenomenon, which might be named after its observer, Peter Firth. It was the subject of our latest Friday afternoon meeting. Firth’s Law is less about the propensity of toast always to fall with the buttered side landing on the carpet, but more with the tendency in human affairs for ‘the best laid schemes o’ mice and men to gang oft a-gley’, as Robert Burns put it. More formally it is known as the Law of Unintended Consequences. For example, prohibition in the USA led to an increase in alcoholism, seat belts in the UK to more risky driving, and the Imperial British government’s policy of giving rewards for dead cobras to a domestic industry of rearing the beasts. The clever bit in Peter’s talk was to apply all this to the rise of the Cardinals in the eleventh century. Attempts either to reform the Church, or to keep it under the control of the Roman nobility or the Holy Roman Emperor, or even to enhance the role of the Cardinals seemed each in turn to have led to the opposite outcome. Peter’s articles have provided an informative and interesting addition to recent issues of FORUM, but in this fascinating talk he placed the minutiae of medieval Papal politics in a much wider context. We are grateful for his authoritative and stimulating contributions.

John Sharp

The Plague

A Short Story

The village was desolate in the overcast sky of late winter. It was not raining, but still few people were about. What was most striking was that no groups of children could be seen in the streets, or women gossiping, just a lone boy sitting outside a cottage, playing with a shapeless piece of wood and a housewife attending her small garden. The village inn was deserted. Some signs of life were evident, as smoke rose from the chimneys, and in the fields outside farm workers, attended their flocks, which could not be left on their own, or looked to the crops, which obeyed the laws of nature not those of the present time. However, on the whole people did not care to venture far from their cottages.

Outside the parish church was a bench and on it sat the vicar, Reverend Michael, and not far away, but sufficiently far away, sat John, the herbalist. They were great friends, partly because they were the only two learned men in the village. And they were learned. They kept in touch with the world outside them, through letters from friends, books, and occasional visits to the great capital, London. Michael, of course, had been to university, and John, though not formally educated, was both literate and well-informed. Much of his expertise was traditional, acquired from his father, but he made great efforts to acquire wider knowledge. He had learned to read by means of the famous work of Nicholas Culpeper, known then as ‘The English Physician’. Culpeper based his ideas on experience and reason rather simply the traditions of the past. He listed the herbs he knew about and how they might be used to promote physical health. The herbalist in Culpeper’s eyes was indeed a physician.

The clergyman was the younger of the two, his face still showing the enthusiasm and idealism of youth. John was a man in his middle years, swarthy, coarser in appearance than his friend. He was known as a man of principle, but also a practical man.

Both were intelligent enough to realise that the plague spread somehow through contact. They observed that if one person caught it, the rest of the family soon followed. They didn’t understand if this was through touching, something in the air, or even transmission through animals or insects, but they knew enough about the practice of quarantine to urge their neighbours to reduce contact to the minimum necessary. They went further, arguing that there was a moral duty in keeping the village isolated from those around it. This led them to persuade their neighbours to close the village, either to anyone coming in or anyone going out, to isolate themselves from the world. They told them that they could not be worse off this way, and that it was both a charitable act, to protect others, and a selfish one, to protect themselves. In any case, there was enough food stored in the barns or to be sought in the woods outside to keep them alive.

They were two men who liked to debate, to speculate.

‘I am glad that you don’t put out in your sermons the argument that this plague is sent by God as a punishment for our sins.’ said John.

‘No,’ Michael replied, ‘this has often been given as a reason, but I cannot see the sense of it. If God wants to punish sins, why should He inflict the suffering equally on the innocent and the wicked?’

‘So, if the plague was not sent by God, that makes Him less powerful.’

‘The plague was not sent by God, but it was allowed by God. God allows evil, because without evil there can be no good. God allows evil as a test. How we react to this plague determines what is right and what is wrong.’

‘You think that what we have done in this village is right? By ‘we’ I mean you and me, because without us it would not have happened.’

‘I believe it is right. We have acted with charity, for what we thought would be the greatest good.’

‘But God tests our brains, as well as our consciences. This plague is not like an ordinary illness or infirmity. It is something different, something we still don’t really understand.’

‘You are right, it is a test for our brains as well. You of all of us, John, know how much Natural Knowledge has advanced in recent years, how we understand much more of the way things around us work. But the plague is still something of a mystery.’

‘I have been lucky enough to read the books my father collected and meet some of the wise men of our day, men who even now are debating in this new Royal Society in London, which the King has approved. Robert Boyle even spoke to me once of how the new knowledge is advancing, through practical experiments as well as theorising. I have even heard of an Italian astronomer who showed how the planets move.’

‘Some people believe that this plague is caused by the position of the planets.

‘That’s what the astrologers tell us, and even Culpeper believed it, but I prefer to look for more down-to-earth explanations.’

Their discussion could have gone on without an end in sight, but they were interrupted by the arrival of a woman of the village, who approached and then stopped, as she had learnt, a distance away from the two men.

‘What is it, Alice?’

‘Old Mary, sir. I have not seen sight or sound of her for two days, and normally she sits on a chair outside her house for an hour or two, even in these times, at least in good weather.’

Mary was an old lady, who lived alone in a cottage at the very perimeter of the village. She didn’t mix with other people, but always had a smile and a gentle greeting for them, especially the children.

Alice was often regarded by her neighbours as being a little too interested in the affairs of others, but her inquisitiveness made her a good observer, Michael acknowledged her usefulness. ‘Thank you for coming, Alice. We’ll certainly look into it.’ With a self-satisfied smile, the informant bustled off.’

‘One of us must go and see,’ said Michael, ‘it can’t be both of us, but she may be in trouble. I’ll go.’

‘I agree that only one of us should go, but why you?’ said John. ‘If she is sick, as she probably is, my herbs may bring her some comfort, not much I agree, but some ease of her suffering.’

‘I doubt not, John, that your herbs have sometimes worked wonders, but Mary is an old woman, and if she is sick, it is likely to be mortal. It is spiritual help that she needs.’

‘Better then that I take the risk and not the guardian of souls,’ John said with a laugh. Then more seriously he continued. ‘I know, my friend, that it is your vocation to help the soul of man, whatever that is, to face the terrible realities of existence, but I am of a more practical mind. If I can help to save her body, let me do it. If I can’t, then I give way to you.’

‘The soul is more important than the body. As, in these times only one of us can attend her with any safety, I should go.’

John reflected for some minutes before speaking. ‘I know it is dangerous to speak my mind openly, but I cannot believe that the other world comes before this one. In his books, Francis Bacon encourages us to base our understanding on observation, reason and experiment. Then there’s William Harvey who shows how the blood circulates in our body. Great advances are being made in our understanding of nature through studying the world around us in a practical way. My gifts are small, but they are a part of that movement. I don’t deny that your desire to help arises out of compassion, in which there is great merit, but life is the important thing. If I can save a life, that must come first. God is a long way away, and what He means by sending us this plague is anyone’s guess. But I will not simply submit to fate. If it overtakes me, so be it, but it will not defeat me until I have at least tried to fight against it.’

Michael stood up and looked at his friend squarely in the eye.

‘There may be a risk, but, come on, we’ll go together.’

John Sharp

The Descendants of Charles Scarisbrick

Charles Scarisbrick (1801-1860) was largely responsible for the rebuilding of Scarisbrick Hall in the mid-19th century. He was something of an enigma. A polymath interested in all branches of science and the arts, he was a prodigious collector of works of art and antiques and also a shrewd business-man investing in property as well as mines, railways and chemical works!

Charles never married but had a long-term relationship with Mary Ann Braithwaite who lived at his house in Suffolk Place London. Whether they didn’t marry because of religious differences or social status (she was a gardener’s daughter) is unknown but they had three children William (1837-1904), Charles (1839-1923) and Mary Ann (1841-1902).

When Charles died his children were unable to inherit the entailed estate because they were illegitimate, but all the land Charles had purchased in North Meols, Crossens and Southport as far as the Birkdale boundary, as well as the proceeds from the sale of all his collections were left in Trust for the three children. The Trust was run as a business by the two men that Charles trusted, William Hawkshead Talbot and Thomas Part. Talbot was a Chorley surveyor, who had acted as Charles’ agent since the 1830s. Part was a Wigan solicitor, whose friendship with Charles went back to childhood. In his will, Charles describes them as ‘worthy friends’.

The will directed that the three children should each have an annual income from the Trust of £3000 (equivalent to approximately £3 million today), in addition to a share of any surplus capital. From the 1870s they never drew less than £10,000 each per year. The Will made all three children extremely wealthy, but the provisions were not typical of the English landowning class into which their father had been born. The landowning class set great store by primogeniture. The eldest son inherited the estate but would be expected to make appropriate arrangements for younger siblings and other family members. All three of Charles’ children are included in ‘The Great Landowners’, John Bateman’s 1870s listing all those who owned at least 3,000 acres, worth at least £3,000 per year. The Scarisbricks are an extremely rare example of three siblings being included. Despite their appearance as ‘Great Landowners’, neither William nor Charles would count as true country gentlemen. Their education had been in Germany rather than at an English public school and neither had a ‘seat’. William is one of only five entries giving a London address (5, Palace Gate), while Charles is unique in not having a British or Irish address, but being listed as ‘res Frankfort, Prussia’. Mary Ann was the only one to enter ‘society’ and, as we will see in a later article, she did so through marriage.

William Scarisbrick and his Descendants

Although born and initially educated in England, William lived for all his adult life in Germany and died in Wiesbaden in 1904. There is no record of visits to Southport or Scarisbrick. He and his German wife had a son, Charles Frederick Maria Scarisbrick (1860-1908). In 1881, Charles is listed as a student in London, and four years later, it was there that he married Rosalie Nevison, daughter of a British army officer. It is not clear where the family lived, but his son later moved to Nairobi and his daughter married a German Count. He died at Menton on the French Riviera, while on holiday there in March 1908 and was the first person to be buried in the newly erected Scarisbrick Mausoleum at Crossens. His widow lived until 1952, latterly with her daughter, and they too are buried in the Mausoleum. No surviving descendants are known.

Charles Scarisbrick and his Descendants

Whereas William and his family only seem to have had a posthumous connection with their ancestral home, Charles and his descendants were more actively involved. Like his brother, Charles’ early adult life was spent in Germany and on 9th May 1860, only a few days after his father’s death, and only shortly after he came of age, he married, Bertha Petronella, daughter of Ernst Marquard Schonfield, a well-known jeweller, of Hanau, Germany.

All their three children were born in Germany and their two daughters married Germans. The family seem to have led a peripatetic life but with a Southport base. In 1888 they settled in Scarisbrick Lodge in Queens Road. It was a pattern of Sir Charles’ life that he regularly spent March and April in Germany and spent the winter in the Riviera where he had a villa in Menton.

Politically Charles was a Conservative, although not a particularly ambitious one. He was Mayor of Southport in 1901, knighted in 1903 and made Deputy Lieutenant of the County Palatine of Lancaster in the following year. He was in poor health and in 1906 he resigned as President of the Southport Conservative Association and member of the Southport Council because of it. Following this he and his wife spent some time recovering at Castle Puchof on Bavaria and then at Wiesbaden.

When World War 1 broke Sir Charles and his wife were staying in the Russischer Hof in Munich and he was arrested and placed in confinement in the Ruhleben internment camp near Berlin. Bertha, Lady Scarisbrick died in Munich in 28th April 1915. Her remains were temporarily interred in the Munich Cemetery and reburied at Crossens in 1922. Newspaper obituaries describe her as ‘a prominent Roman Catholic’ who was widely known for her many activities, and highly esteemed for her generosity to the poor of Southport and district.

Sir Charles Scarisbrick returned from Germany in September 1915 and initially went to stay with his son at Greaves Hall. He died at Scarisbrick Lodge on 14th January 1923 after a short illness. As well as listing the various offices he had held, his obituary stated:

he had resided in town since 1888, but long before that he was well known in and closely associated with it. As a landowner he took a great interest in the development of the borough, and he was largely responsible for the reclamation marsh land on Southport foreshore, land which is now valuable agricultural land. Through his efforts too the trustees were encouraged to sell land at one half its market value for churches and schools and in some cases the land was transferred free of cost. This was the case with Southport Infirmary, on the opening day of which he handed the chairman a cheque for £7000 for the endowment of a cot in the children’s ward, to be named the ‘Bertha Ward’ after his wife.

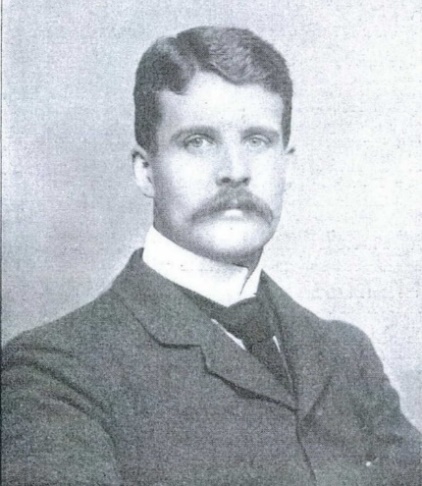

Sir Thomas Talbot Leyland Scarisbrick 1st Baronet

Thomas was the only son and youngest child of Sir Charles. He was born on the 28th May 1874 in Germany but by 1881 had returned to England. In 1895 he married Josephine Chamberlain, youngest daughter of William Chamberlain of Cleveland Ohio. The wedding was at Hillingdon Court, the country seat of his cousin, Captain Naylor Leyland, who was already married to the bride’s sister, Jennie (1862-1932).

As a county magistrate, Tom took an active part in the life of ‘borough and district’. In 1902 he succeeded his father as Mayor of Southport, but unlike Sir Charles, Tom was a Liberal not a Conservative. He served as Liberal MP for South Dorset from 1906 -1910 and was created 1st Baronet of Greaves Hall in the birthday honours list in 1909.

The electoral rolls of the time show that as well as having a property in his constituency, Osmington House, Weymouth, he also had a house in London (3 Mount St) and Greaves Hall in Banks, which had been built on a 124 acre site given to him as a wedding present by his father.

Sir Tom purchased Scarisbrick Hall in 1923, and in 1924, having wrested control of the Scarisbrick Estates from the London based solicitors he decided to sell the whole of his agricultural estates in Banks (representing approximately 4000 acres). The tenants were given the first option to purchase their holdings and his Trustees agreed to allow 60% of the purchase money to remain upon mortgage at 5%. Greaves Hall stood empty while the land was cultivated by the consortium. On 3rd May 1932 the house was leased to Dorothy Glaister Greaves and became Sherbrook Private Girls’ School.

Sir Tom had two sons both born in London. Everard, later Sir Everard, born in 1897 and Ronald who was born two years later but died at Greaves Hall in 1913 after a short illness.

Sir Tom and Lady Scarisbrick travelled widely and he was a keen motoring enthusiast. He was a member of the RAC and was reputed to own one of the first motor cars in Lancashire, a Gobron-Brille car which he had imported from France. He undertook motoring challenges on the continent and in 1904 was fined £20 at Southport’s magistrate’s court for ‘furiously driving a car in Lord Street’.

He died at Scarisbrick Hall on 18th May 1933 from pneumonia and is buried in the Scarisbrick Mausoleum. His widow, Josephine, lived on until 1950, partly with her son at Scarisbrick and partly in a London flat in Curzon St.

Sir Everard Talbot Scarisbrick

In the 1911 census Everard is living at Greaves Hall with his parents, brother, maternal grandmother, tutor and eight servants. During WW1 he enlisted in the 7th Battalion the Kings Liverpool Regiment and on 16th October 1914 he was promoted 2nd Lieutenant, stationed at Bootle.

In 1919 Everard married Nadine Celeste Sybil formerly Williamson nee Brumm. Nadine’s father, a shipping agent, was born in Hanover but had acquired British citizenship. They had no children.

Sir Everard appears several times in the interwar years in the Tatler magazine, mainly in pictures of ‘Shoots’ both at Scarisbrick Hall and on other estates such as Nantclwyd Hall, home of the Naylor Leylands.

In 1924 he rescued his mother and father from a fire at Scarisbrick Hall. The alarm was given at 3am when Everard’s wife

was awakened to flames and smoke in her room. She roused her husband, …, who, having got his wife to safety, tried to arouse Sir Talbot and Lady Scarisbrick._ They were imprisoned in their room, with their retreat cut off by the flames. Mr Everard Scarisbrick, barefooted, and dressed only in pyjamas, reached the lawn, and, securing a ladder, climbed to the bedroom window and rescued first his mother, then Sir Talbot, both of whom were suffering from the effects of smoke. Mr Everard then returned up the ladder and rescued a Great Dane which was sleeping in Sir Talbot’s room. Mr Everard headed a volunteer fire corps,and battled with the flames until the arrival of the Southport Brigade”. Other reports say “Lady Scarisbrick was hurt by a falling picture and Mr. Scarisbrick fell while taking a pet dog down the ladder, but was not hurt. Three rooms were gutted, and damage was done to antique furniture.

During the Second World War Scarisbrick Hall was largely given over to the Red Cross to use as a military hospital. A few rooms were retained for the use of the family and Lady Scarisbrick busied herself by creating a library for the use of the patients.

The grounds were also opened to raise funds for the Scarisbrick Nursing Association and the Cancer Fund. Free admission was given to those in uniform.

In 1945 the remaining contents of the hall were sold and the hall itself, along with 476 acres of grounds were put up for sale. The hall was bought by the Church of England Board of Finance for an estimated £60,000.

After the sale of the Hall Sir Everard went initially to live in London although he travelled extensively. He died in Norfolk in 1955. He and his wife are buried in the family mausoleum at Crossens.

Mary Ormsby

Contacts

Chair: Alan Potter

alanspotter@hotmail.com

07713 428670

Secretary: Roger Mitchell

rg.mitchell@btinternet.com

01695 423594 (Texts preferred to calls)

Membership Secretary: Rob Firth

suesmembers74@gmail.com

01704 535914

Forum Editor: Chris Nelson

chris@niddart.co.uk

07960 117719

Facebook: facebook.com/groups/southportues

See our archive for previous editions of the SUES Forum!