Introduction

The recent death of Hazel Fort, chair of SUES since 2016, is a huge loss to the society. We begin this edition with tributes to her. As she would have wished, our scheduled meetings have been and are continuing, as described below. The committee made a unanimous decision to appoint Alan Potter as chair until the matter can be formally resolved at the next AGM.

Hazel Fort

The death of our chair, Hazel Fort, came as a considerable shock and a cause of great sadness. We are still not fully aware of the details, but are anxious to pay tribute to her for all her work for SUES.

Hazel had a wide range of interests and commitments in the South Sefton area, in addition to her connection with SUES. These included the Merseyside Home Watch and a school chaplaincy. She was an active member of St. Helen’s Church in Crosby, serving in lay ministry, as sacristan and Eucharistic minister. She lived on her own, though we believe she has family in Oswestry. Responsibility for funeral arrangements is being undertaken by members of St. Helen’s Church. The funeral will take place on 4th March at 11.30 am.

Hazel had been a member of SUES for some years before she stepped in to take over the role of chair from Timothy Robey in 2016. This was a critical moment for the society, which was suffering from declining membership while at the same time being the recipient of a very substantial bequest. This led to considerable debate about future policy, which led in the end to the new-look SUES which operated so successfully in 2019. Hazel presided over these developments in her own distinctive style with a faith in the future, which gave support and confidence to all involved. Her contributions to FORUM, reflecting on this difficult year with humour and resilience, are typical of her approach. Some will also remember her thought-provoking and moving presentation on the difficult topic of dementia.

Hazel’s commitment and cheerful confidence will be greatly missed. We send our condolences to family and friends.

Hazel Fort: A Reminiscence

I was so shocked to hear the sad news of the death of Hazel Fort. I have known Hazel for a long time. I first met her when as the Chair of Sefton Home Watch I went to Crosby with a police officer, to try and get the Home Watch started again in the Crosby area. A meeting of residents was held and Hazel agreed to take over as the Chair and once again she rescued an association that would have closed without her help.

We worked together for many years promoting Home Watch in the Sefton area supporting each other in our endeavour to work with the Police and be a support to our members. Our aim was to try to prevent the residents of Sefton from becoming the victims of crime. Hazel took over the Chair of Sefton Home Watch when I stepped down.

Hazel was a very loyal friend, a hard-working colleague who always thought of other people and their needs before herself. Only this morning I left a message on her answer machine; now sadly I know why she was unable to answer her phone.

I will miss Hazel very much; she leaves a legacy of helping and being a friend to so many people in so many different ways.

Margaret Jepson

Forthcoming Talks

We have arranged two more talks for March, both to be presented by Peter Firth, and both on a Friday afternoon from 2.30 pm to 3.30 pm. The first is based on our intention to run the Normans course some time in 2021-2; the second is a follow-up to Peter’s three articles on the Cardinals, the third of which will appear in the March edition, to be circulated on 15th or thereabouts. As with previous talks, let Alan Potter know if you want to receive the link (contact details below).

March 5th. England under the Normans: Primary Sources

Last Autumn, we had intended to run this 10 week course. The arrival of Covid 19 has brought about its postponement. We intend to reinstate it later this year or early next. As a taster, this one-off lecture will focus, not on the events of this important part of our islands’ history, but on the actual source material for this period. The Domesday Book and Bayeux Tapestry come immediately to mind, but there are a number of other valuable sources available. Not only will we consider these but, equally important, the way in which historians actually use them to interpret past events.

March 26th. The Rise of the Cardinals c. 1049-1100

Forums 15-17 include three parts of a PhD thesis which began by comparing some of the scandals at the heart of the papacy, over a millennium apart. This was followed by an analysis of events during the second half of the eleventh century which shaped the formation of a rudimentary College of Cardinals but, nevertheless, one recognisable today. Its members had acquired a key function in participating in the political control of the Apostolic See through the underlying themes of Reform, Reaction, Counsel, Ambition and Self-Awareness. This lecture will provide, not only the opportunity for discussion on this significant development in papal politics but will highlight the re-occurring phenomenon in human decision-making: The Law of Unintended Consequences.

Monday Morning Course

Roger Mitchell is continuing his sessions on 18th and 19th Century Travellers.

Monday 22nd February – ‘A Travel Revolution’ – Railways and Steamships

Monday 8th March – ‘Feisty Ladies’ – Women Travellers from Victorian England, especially Marianne North and Isabella Bird

The format of this course will now be familiar to those who have participated. Any other member is welcome to join in. You simply need to let Alan Potter know (contact details below).

Talk on Montaigne

Another Friday afternoon zoom talk, this time by John Sharp, raised our spirits, opened our eyes and stimulated all manner of questions ranging from Montaigne’s famous speculation that cats may play with us just as much as we play with them to even deeper thoughts about the meaning of life. For me at least, Montaigne was little more than a name, a 16th century French essayist and philosopher, whose voluminous writings were well known on both sides of the Channel. He was a cheerful man, but he lived in a cheerless age – the French Wars of Religion. As Mayor of Bordeaux, he had to tread a difficult and dangerous path, combining political skills with a genuine desire for moderation and compromise. He valued seclusion and scholarship and found both in the tower library of his family chateau.

With an effective combination of analysis and anecdote, John turned a name into a personality and a very human one with weaknesses and contradictions but, above all, a zest for life and a determination to understand it as best he could. By the end of the talk and the lively discussion that followed it, we were quite prepared to discard the question mark of his title ‘Montaigne- the first modern man?’ and enrol Montaigne as an honorary member of SUES.

Roger Mitchell

The Rise of the Cardinals c. 1049 – 1100: Reform, Reaction, Counsel, Ambition and Self-Awareness

Part 2: Papal Reform

The previous part of this article can be found in Forum 15. This described the control of the papacy in the hands of two competing Roman families during the first half of the eleventh century, until the intervention by military might of Henry III, the German emperor. Thereafter, the papacy was set for a great leap forward, initially with the imperial appointment of two short-lived German popes.

Pope Leo IX

Emperor Henry III

In 1049 after a successful imperial career, Bruno, bishop of Toul in France and distant relative of Henry, became his next appointee as Leo IX. His pontificate became a watershed in papal history. Focusing on widespread reform, he immediately insisted his elevation should be the result of acclamation by the Roman clergy and people, following the declaration of his renowned namesake, Leo I.

Much as he sought the support of Henry, his elevation and those of his two predecessors were still dependant on lay intervention, becoming pope by imperial sanction. No elections had taken place. Leo was determined to remove this control, otherwise the papacy would still be subject to secular control – the emperor or Roman aristocracy.

The same applied to Church Councils where pope and emperor would sit as co-presidents – an arrangement soon discontinued. At breakneck speed across the empire, Leo held a series of Councils as sole president, spending barely six months of his six-year pontificate in Rome. His reform agenda comprised: the buying and selling of clerical offices – simony – particularly when appointing bishops; clerical chastity with many clerics, including bishops, having wives or concubines; and lay investiture whereby bishops received their office, not from fellow bishops, but from the king or leading noblemen.

Leo’s strategy was to wrest control of the Church from all secular influence and establish the primacy of the Apostolic See over the universal Church. But, to achieve this, he needed help.

Gradually, a dramatic institutional and ideological transformation took place, in part the result of papal action, but also shaped by concurrent events. Firstly, Leo acknowledged the cardinal-bishops as a body to which he and his immediate successors appointed like-minded reformers. Clear evidence of the importance of the cardinal-bishops was expressed in Leo’s letter of 1053 to the patriarch of Constantinople.

Like the immoveable hinge which sends the door back and forth, Peter and his successors have judgment over the whole Church. Therefore, his clerics are called cardinals, as they belong more closely to the hinge by which everything else is moved.

Because of the limitation of seven cardinal-bishops, Leo’s recruitment policy developed by appointing more reform-minded individuals to high papal office as cardinal-priests and cardinal-deacons. Its success led to the development of a corporate body within the papacy which, four years after Leo’s death, was able to assert authority in a quite dramatic way. This group was able to expand and regenerate itself, possessing a sense of collective responsibility and powerful continuity.

Beyond Rome, Leo’s cardinal-priests/deacons undertook responsibility as papal legates, presiding at Church Councils. Even a lowly sub-deacon, Hildebrand (future Gregory VII) could go to Germany with full papal authority to depose bishops who had failed to comply with papal rectitude.

The self-awareness of this inner core of papal government, embracing key personnel – Humbert of Moyenmoutier, the papal chancellor, St Peter Damian and Hildebrand – became the glue of Church reform. All of Leo’s cardinal appointments had a monastic background, many as head of monastic institutions. This included Desiderius, abbot of Monte Cassino (future Victor III), who became cardinal-priest of S. Cecilia.

Despite the progress made by Leo and his immediate successors, two events clouded the reformers’ horizon. In 1056, Henry III died, aged 40, being succeeded by his six-year-old son, Henry IV. During the ensuing regency, a major source of secular support for the papacy disappeared.

However, a bigger problem arose with the death of Stephen IX in 1058, whilst many of the papal inner core were outside Rome. Cardinal-bishop John II of Velletri, an appointment before Leo IX’s elevation, was elected Benedict X, apparently by Roman acclamation, although probably the result of bribery by the Roman aristocracy to whom Benedict had family connections. Nevertheless, his pontificate had a veneer of legitimacy, with support from one other cardinal-bishop. This break in their ranks left the remaining five cardinal-bishops in a very precarious situation. Together with Hildebrand, they met at Siena, electing Gerard, bishop of Florence, as Nicholas II. But it was only through the use of military force and Jewish connections within Rome that they were able to oust Benedict. However, a major problem persisted – how to achieve retrospective legitimacy for Nicholas.

The solution came with the 1059 Papal Election Decree, formulated by the five cardinal-bishops. This defining moment would have a lasting effect right down to Pope Francis’ elevation – the first step by this group of churchmen in determining papal elections. The subsequent journey has been far from straightforward. Nevertheless, this decree, to which seventy-five archbishops subscribed, together with patriarchs and bishops, opened the way towards today’s conclave.

Its key aspect gave cardinal-bishops sole rights in future papal elections. Adding further legitimacy to Siena, future elections should ideally be held in Rome and the candidate should also be Roman. However, these requirements could be waived under extenuating circumstances (as had just happened). The remaining cardinal ranks and other Roman clergy had the right of assent, as did the populace of Rome, but this did not confer any right to object to the election. In recognition of previous imperial involvement, a so-called ‘king’s clause’ was introduced, allowing for confirmation or recognition of the cardinal-bishops’ decision but, again, with no right to object. The Roman aristocracy had no involvement under this decree.

Another important aspect of this legislation, previously somewhat vague, was that papal powers were assumed on election and not enthronement, adding further to the legitimacy of Siena. In a succession of letters, Peter Damian was responsible for the development of a cardinal ecclesiology. The cardinal-bishops were sentinels or eyes of the papacy, evolving into papal custodians and, finally, papal guardians, effectively governing alongside the pope, even to the extent of censuring an erring pope.

This decree created an initial hierarchy of five cardinal-bishops, four cardinal-priests and three cardinal-deacons, as well as a new papal institution. The genesis of this College of Cardinals provided a constitutional foothold in future papal elections. Effectively, a monopoly of self-perpetuation was being crafted which, in theory, should always guarantee the future election of reform-minded pontiffs. Although unknown at the time, it would also open the door for even greater cardinal participation in papal government.

The subsequent decade and a half was largely a period of consolidation for the papacy and Roman cardinalate. Monastic recruitment, particularly from nearby Monte Cassino, continued and cardinal legates were given more power ‘as if the pope himself were present’. Cardinal-bishops were spending less time in Rome. As a result, an increase in subscriptions to papal documents by cardinal-deacons and cardinal-priests only enhanced their status.

Another development within the Roman Church would also lead to another major step forward for the cardinalate. In a little-acknowledged and undated papal decree during the pontificate of Alexander II (1061-73), the twenty-eight cardinal-priests were given quasi-episcopal rights. Focusing on bad behaviour and ostentation, the priests of all other Roman churches came under the jurisdiction of the cardinal-priests. Whether the simple extension of an existing institution (the twenty-eight cardinal-priests) or the result of pressure for more authority is unknown. But, in giving them supervisory and administrative responsibility on top of their duties at the four major basilicas, the status of the cardinal-priests will have improved even further. In several cases, archpriests were brought in to support the cardinal-priests in their own tituli.

In terms of shaping the future College of Cardinals, albeit completely unwittingly, this decree of Alexander II may rank alongside Nicholas II’s papal election decree, as will become evident. The next major change within the Roman cardinalate would be even more dramatic than earlier developments.

Peter Firth

Look Back to a Happier Future!

In talking with friends recently, mostly on-line of course, it is surprising how many offer the same piece of advice. This is often ‘we must look forward, there is no point in looking back’ and equating this with ‘look to the future – be positive’. However, such general advice, well-meaning though it is, may not always be helpful and can often go against what scientists and other researchers have found in reality. This is such a case as there is much to be gained from looking back; in fact, there can be a joy in reminiscence.

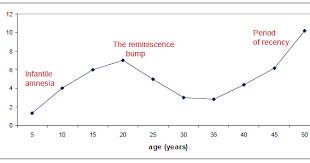

Scientific research over many years has found that there is a tendency for older adults (those over forty) to have increased or enhanced recollection for events that occurred during their adolescence and early adulthood. The study of autobiographical memory (our recalling of episodes from our lives based on personal experiences, objects, people and events experienced at particular times) led to the plotting of the ages of encoding of memories to form the ‘lifespan retrieval curve’.

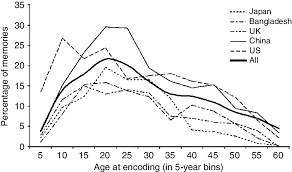

The lifespan retrieval curve is a graph that represents the number of autobiographical memories encoded at various ages during the life span. The curve presents three different sections. The first is from birth to five years old, a period termed childhood amnesia, the second from around 16 to 25 years old known as the reminiscence bump and the third, a period of forgetting from the end of the reminiscence bump to the present.

The reminiscence bump occurs because our autobiographical memory storage is not consistent throughout our lives. In fact, memory storage increases during times of change either in oneself or in our life goals, such as the significant changes in identity that occur during adolescence. Researchers have consistently observed the reminiscence bump, the period of increased memory accessibility in participants’ lifespan retrieval curves, and the bump has been reproduced in different countries (see the graph below) and under a range of study conditions. Individuals typically recall a disproportionate number of autobiographical memories from those periods and the reminiscence bump accounts for this disproportionate number of memories. This is due to the fact that the memories found within the reminiscence bump significantly contribute to an individual’s life goals, self-theories, attitudes, and beliefs. In addition, life events that occur during the period of the reminiscence bump, such as graduation, marriage, or the birth of a child, for example, are often very novel, thus, making them more memorable.

Researchers have suggested three possible hypotheses for the reminiscence bump: a cognitive account, an identity account and a biological account.

The cognitive account suggests that memories are remembered best because they occur during a period of rapid change followed by a period of relative stability. The novel events are subject to greater elaborative cognitive processing leading to the stronger encoding of these memories.

The identity account suggests that the reminiscence bump occurs because a sense of self-identity develops during adolescence and early adulthood. Research suggests that memories that have more influence and significance to one’s self are more frequently rehearsed in defining one’s identity, and are therefore better remembered later in life.

The biological account suggests that genetic fitness is improved by having many memories that fall within the reminiscence bump. Cognitive capacities are at their optimum from the ages of 10 to 30 and the reminiscence bump may reflect a peak in cognitive performance.

Therefore when we, in later life, seek to retrieve memories it is not an even experience either as we are all associated with this curve. It is very unusual to remember events before the age of five, then retrieval climbs quickly reaching a peak by about the age of 20 and declining after around 25-30 and flat lining. Then recall starts to climb again to a much smaller second peak (about half the size of the first) by age 75. This weak bump is termed the ‘recency effect’ showing we remember recent events better than older ones. However such memories are not as strongly embedded as those in our early life and looking back at them is not a negative thing to do but a positive, enjoyable one. In fact, we can readily access happy happenings from the reminiscence bump whereas the recall of sad events remains stable across the life span and does not exhibit a bump in recall.

As people reminisce, we light up significant parts of our brain including both areas that store our memories and areas involved in generating feelings of reward. Both use the neurotransmitter dopamine to make things happen. This stimulation causes two simultaneous effects; the first is that your brain gives you a reward when you reminisce so you want to repeat it and the second is that the reminiscing-activated neurotransmitter is involved in learning and motor function too, not just reward. Therefore, being nostalgic affects not just our attitudes but our bodies – people have even reported eyesight improvements and improvements in exercising abilities. So stimulating dopamine is what nostalgia is good at and since there is, typically, much less dopamine in the brains of senior citizens, this is good news. So sit back, reminisce away and enjoy the rewards. In such a high emotional and mental state when thinking about the past, you will be able to look to the future with renewed clarity and confidence.

Alan Potter

Contacts

Chair: Alan Potter

alanspotter@hotmail.com

07713 428670

Secretary: Roger Mitchell

rg.mitchell@btinternet.com

01695 423594 (Texts preferred to calls)

Membership Secretary: Rob Firth

suesmembers74@gmail.com

01704 535914

Forum Editor: Chris Nelson

chris@niddart.co.uk

07960 117719

Facebook: facebook.com/groups/southportues

See our archive for previous editions of the SUES Forum!