Introduction

In the current circumstances the plans we had to resume our traditional face-to-face events are unlikely to be implemented soon; we will have to wait for a marked relaxation in Covid-prevention measures to do that. However, we are determined to keep SUES going by providing what intellectual and educational stimulus for our members can be achieved within the constraints. This publication, SUES Forum, will continue, though we intend to regularise the timing by having an edition available about the 15th of each month. In addition, we intend to launch an exciting new venture: a course with something like the traditional content, but using different modes of communication. Our first attempt to do this will be Roger Mitchell’s course on English Travellers. Details are given below.

The committee has devoted much thought and discussion to the best way forward and we have decided to sign up to Zoom and use it as a basis for online communication, at least for the present. Two committee meetings have already been held in this way. Alan Potter has been instrumental in leading us forward and providing guidance and support. His contact details are given below and may be used by anyone seeking help or guidance.

This edition of Forum contains an article on Scarisbrick Hall and its family. We are grateful to Mary Ormsby for this, which is the first of a sequence based on her researches. The article is in fact a shortened version of an essay. If you would like to read the full version, complete with references, contact Mary on mormsby@btinternet.com.

In keeping with our intention to broaden the scope of our topics, Alan Potter has contributed another article with a scientific flavour. Most of you will be aware of David Attenborough’s warnings about plastics, and Alan’s comments will ensure that you have a greater understanding of this issue.

We have been reminded that a new list of lectures, provided by Gresham College, is available online. If you are feeling the lack of this form of event, do have a look at what is available. Just type the name in your search engine.

We have no responses to add to this edition, but we hope that members will have something to say about our future plans and these comments will appear next time.

Future Plans: Course on English Travellers

In Forum 11, I wrote that I wasn’t going to let a World Pandemic stop me from giving my annual Southport course, even though arrangements will need to be different. Fortunately, English Travellers is an appropriate topic, because we have the words of the travellers themselves as the basis of our work. In November and December, we will look at two 17th century travellers, Samuel Pepys and Celia Fiennes, and depending on how that goes (and how the pandemic goes) we may move on to the 18th and 19th centuries in the new year.

The course will be an experiment. There will be no charge and we hope that as many members as possible will get involved. That involvement may just be reading documents sent either by post or by email, but we hope to encourage as many of you as possible to use Zoom to discuss the travels of first Samuel Pepys and later Celia Fiennes. For Celia Fiennes, you will also be able to watch and listen to an introductory lecture by me. Like all my previous Southport courses the Zoom sessions will take place on Monday mornings and, as in the past, there will be no requirement to attend every session. There will be special arrangements for those of you who get your copies of Forum by post. These will be explained on a sheet enclosed with this mailing.

This is how it will work:

On Monday 2nd November, SUES will send all members an email entitled ‘Samuel Pepys’. There will be two attachments, a short Powerpoint introducing Pepys and asking some questions about his trip, and a Word Document which has the text from Pepys’ diary describing his trip to Bath and Bristol in 1668. What you do with this material is entirely up to you.

- You may treat it as junk mail and dispose of it accordingly. (If you prefer not to receive it at all, please let me know – my contact details are at the end of Forum 12)

- You may regard it as a supplement to Forum and browse or read through it but not take it any further

- You may want to email me with your thoughts and questions

- However, what I really hope that you will do is get so interested in Pepys that you want to discuss him with me and with other members. This is where Zoom comes into use. You may already be using it or you may be a newcomer, but as long as you have a computer, iPad or tablet with built-in camera, you will be able to join in. You will need to register for Zoom but there will be no charge because SUES now has a group membership. Alan Potter is the committee member with the most Zoom experience. He will be our Zoom host and will lead us through the system, something that he has already done successfully with the committee.

On Monday 9th (and, if numbers require more sessions, on Monday 16th) we will have follow up discussion groups using Zoom. This will be our first zoom session and we want those groups to be small so that newcomers can be guided through the technology which is surprisingly straightforward.

On Monday 23rd November, SUES will send out the material on Celia Fiennes. This will use the same format as Samuel Pepys and will provide an introductory Powerpoint and a Word document containing the text of her travels in North West England. For those who have signed up for Zoom, I will give a live, informal, introductory lecture on Zoom at 10,30am on that same Monday morning.

On Monday 30th November, the course will conclude with a general discussion via Zoom. We hope that we will be able to divide into smaller groups, both to talk about Pepys and Fiennes but also to review the way that the course has been presented.

If you are interested in the Zoom version of the course, please send an email to Alan, if possible by Wednesday 4th November. His email address is alanspotter@hotmail.com and he just needs to know your name, your email address and whether or not you are registered with Zoom. If you are already reasonably proficient at Zoom, that would also be useful to know. He will email you with the time of your group meeting and how to log on.

I look forward to working with you on what I hope will be an enjoyable course. It will certainly be an unusual one.

Roger Mitchell

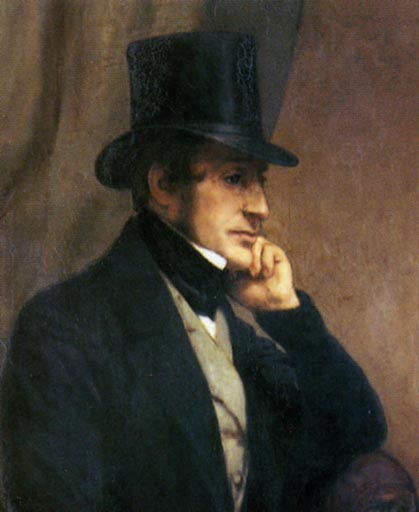

Where Did It All Come From? An Investigation of the Wealth of Charles Scarisbrick (1801 – 1859)

When Charles Scarisbrick died in 1860, he was said to be the ‘richest commoner’ in England. The purpose of this essay is to try to understand how this was possible for a Roman Catholic, whose family had been Recusants, Royalists and Jacobites.

The family origins go deep into the Middle Ages. In 1312 Gilbert de Scarisbrick held 40 liberates of land. A liberate was a piece of land having a value of £1 per year. With wages as low as £2 per year, this represented substantial wealth. For the next two centuries, the Scarisbricks successfully negotiated most of the pitfalls that faced families in the later Middle Ages. They suffered from minorities and wardships but benefitted from marriages and from their contacts with the powerful Stanley family. These connections went back to the 1390s and in the early 16th century, Thomas Scarisbrick (1496-1550) married the illegitimate daughter of the 2nd Earl of Derby.

The two centuries from the 1540s to the 1740s were even more challenging because of the family loyalty to the Catholic faith, which led to their support for Charles I in the Civil War and for the Old Pretender in 1715. Edward Scarisbrick (c1540-1599) was described as ‘conformable’ in religion, though his wife was a recusant and his daughters never came to church. Henry was receiver-general to the 4th Earl of Derby and enjoyed his protection.

Edward had no male heir, so under the earlier entailment he settled his estate on Henry Scarisbrick of Barwick, a distant cousin. Henry married Edward’s granddaughter Ann Parker, thus uniting the branches of the family.

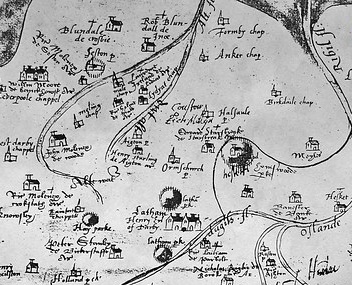

The settlement made by Edward on Henry (1590s) gives an indication of the size of the estate at this time. It was described as the ‘manor of Scarisbrick, two windmills, a hundred messuages, 3,000 acres of land, 2000 acres of land covered with water, 100 acres of meadow, 1000 acres of pasture, 40 acres of wood, 1000 acres of moss and 60s rent in Scaresbrecke, Hurleton, Burscough, Ormeskyrke, Birchacre, Dromblesdale, Aspinall and Snape’.

Edward’s will gives an indication of the size of his household as he makes specific bequests to no fewer than 15 servants. For the size of the house, we can use an inventory from 1608, when Henry Scarisbrick died. Twenty one rooms are listed and a value of £474 13s 4d is given for his ‘goods and chattells and credits’.

The family were Royalist as well as Recusant. While Edward Scarisbrick (b 1609) avoided conviction as a recusant, he was on the defeated side in the Civil War and shared the misfortunes of this. He had to pay compensation and his estates were sequestrated so that when he died in 1652 he was a pauper. The estates were returned to Edward’s son James at the Restoration and he married Frances Blundell (of the Ince Blundell family). When James died in 1673, the Hall had 47 rooms and ‘goods and chattells and credits’ to a value of £1,111 1s 2d.

James’ eldest son Edward became a Jesuit and was a preacher to King James II. The younger son, Robert inherited but left England on the day that James II’s reign ended on 11th December 1688. He returned under license from William III in 1697 and was stated to be a ‘loyal subject’. He was, however, implicated in the 1715 Rebellion. He was attainted and after surrendering himself to the authorities was imprisoned in Newgate. The following year he was acquitted at trial and his estates returned to him. When he died in 1738 his obituary read ’a Roman Catholic gentleman of a very ancient family and plentiful fortune’.

He and his wife Anne, daughter of John Messenger of Fountains Abbey, had plentiful issue – nine sons and four daughters. His eldest son died at sea on his way to a seminary, three other sons became Jesuit priests and three daughters became Franciscan nuns. The estate passed from son to son, first to Robert, who died unmarried, then to William, who left only a daughter and then to Joseph who was also unmarried. In 1778 Joseph moved to London leaving his nephew, Thomas Eccleston, to manage the estate. It is not entirely clear how and when Thomas moved from management to ownership but by 1790 all Robert’s nine sons were dead and Thomas was the only surviving grandson. Thomas’ father, Basil Thomas died in 1789. As a young man he had inherited the Eccleston estate of almost 1,000 acres on condition that he changed his name to Eccleston. In 1749 Basil Thomas married Elizabeth, daughter of Edward Dicconson of Wrightington and 58 years later in 1807, Thomas inherited the Wrightington estate from his mother’s brother.

Thomas certainly had good fortune. He inherited Eccleston from his father, Scarisbrick from his father’s brother and Wrightington from his mother’s brother. He was also able to add to his estate by buying the manor of Halsall. However, his achievement was not just owning land but making the best possible use of it by agricultural improvement. He undertook the drainage of Martin Mere for which in 1786 he was awarded a gold medal by the Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce. He married Eleanor Clifton, daughter of the Cliftons of Lytham Hall, and they had three sons and four daughters. He died in 1809 and in his will Thomas entailed the estate on his three sons, but his second son, William, died a few days before his father and so Thomas, the eldest son, inherited both Scarisbrick and Eccleston while Charles, the youngest son inherited Wrightington. Thomas died in 1833 without a male heir. Charles claimed his estates but his sisters challenged the will, claiming it was never their father’s intention that all the land should be held by one person. The case was finally found in Charles’ favour by the House of Lords in June 1837.

Charles was now a substantial landowner but still far from being the richest landowner in England. It was two great land purchases in the early 1840s and the exploitation of that land over the next two decades that made such a claim possible. In 1842 Charles Scarisbrick paid Sir Henry Bold-Houghton £132,000 for 2,700 acres of land at North Meols together with some smaller holdings in Wigan and in March 1843 he paid £91,000 to Charles Hesketh for lands in North Meols. By these purchases, Charles Scarisbrick now possessed what would become the whole town centre of Southport from Seabank Road and Union Street to the Birkdale border. These purchased lands were outside the entailed estate and would pass as a block on Charles’s death to his three illegitimate children.

How did Charles fund these purchases? As well as involving himself in coalmining, brickmaking, stone-quarrying and chemical manufacture, Charles was heavily involved in land speculation in Paris. Letters within the Scarisbrick papers reveal that by 1833 he owned ‘more than 100 large acres under the walls of Paris’, and later the same year he described himself as ‘the largest proprietor in the environs of Paris’. His object was quite clear ‘Though it has been a present outlay I shall be a heavy gainer in a short time as the Government cannot stir in any one direction in their works without buying me’.

The papers do not make clear if Charles was a heavy gainer, but given that he spent £314,000 purchasing land around Southport, spent something in the region of £85,000 redesigning Scarisbrick Hall, collected pictures and works of art which after his death sold for £45,000, left £161,000 in his bank and only had a £25,000 mortgage –it appears he was very successful.

This was the high point of the Scarisbrick Estate, because, when Charles died in 1860, his estate of over 30,000 acres was split. The purchased lands referred to above went into a Trust for his three children and reverting to his father’s will the entailed estate was split between his surviving sisters – Ann, Lady Hunloke, inheriting Scarisbrick, Halsall and Downholland, and Elizabeth, wife of Edward Clifton, gaining possession of the Wrightington Lands.

The entailed estate eventually came to Rémy Léon, Marquis de Castéja via his marriage to Eliza, Anne’s daughter. Eliza and Rémy Léon’s adopted son, Marie Emmanuel, and his father were personally very active in the management of the Scarisbrick estate. After Marie Emmanuel’s death in 1911 and the impact of the First World War, Scarisbrick became little more than a holiday home for the Castéja family. A number of bad investments and issues with the Agent, which remain to be fully investigated, led to the sale of the estate. The land sale in 1920 was for approximately 12,500 acres of prime arable land which included between 250 and 300 farms. The Hall and 480 acres of the land were bought privately by Charles Scarisbrick’s grandson Sir Thomas Talbot Scarisbrick, in 1923, for an estimated £35,000. Thomas was also a major buyer when the contents of the Hall were sold in the same year.

The un-entailed estate was managed for Charles’ children by the Scarisbrick Trust and the story of those descendants will be the subject of a future essay.

Mary Ormsby

Microplastics – A Man-Made Epidemic?

Science and the discoveries that have been made through it over the centuries have brought untold benefits to mankind. However, on occasions, well-intentioned inventions have brought unforeseen consequences. One such is the production and use of plastics in general and microplastics in particular. Indeed, according to a recent post from Alec McGoran from the National History Museum, microplastics ‘are one of the greatest manmade disasters of our time. They are everywhere – from remote places with no human habitations for hundreds of miles to the food on our plates and the water we drink’.

These micro-plastics that we are being warned against, are plastic pieces that measure less than five millimetres (about one fifth of an inch). Some microplastics have been made small intentionally, for example industrial abrasives used in sandblasting and microbeads in facial scrubs. Some microbeads, for example, are tiny pieces of polyethylene plastic added to health and beauty products, such as some cleansers and toothpastes.

Other microplastics are formed by breaking away from larger plastics such as carrier bags, which have fragmented over time. Natural processes, including sunlight, cause fragmentation, which turns the material brittle and makes it break. But fragmentation doesn’t stop there: microplastics can keep breaking up until they are like dust particles. These are called nanoplastics and have a diameter of less than 0.001mm although it is difficult to measure as it is impossible to separate from the environment. According to Alex McGoran, ‘Micro-plastics are everywhere. They’re in the water, soil and the air we breathe. We use plastic in almost everything, including chairs, carpets and clothes. As we move around, we shed fibres, which float in the air and spread. They’ve even been found in places we previously thought were pristine, like the Arctic and Antarctica.’

There have been many concerns about micro-plastic in drinking water and a recent report by the World Health Organisation (WHO) gathered data from 50 studies to clarify how serious this may be. Microplastics enter the water system in two main ways; firstly from the run-off from land-based sources, including landfills, the breakdown of road-marking paints, debris from tyre wear, the abrasion of synthetic products such as footwear and artificial turf and agricultural run-off, particularly sewage sludge and agricultural plastic such as mulching. Secondly from waste water overflow (both treated and untreated), which includes the breakdown of larger plastics in river catchments, microbeads in cosmetics and fragments of large products that are flushed down the toilet when they shouldn’t be, such as sanitary pads and wet wipes. They also include microplastic fibres released when washing synthetic clothes.

Indeed, as a lot of the clothes we wear are made of plastics such as polyester, nylon and acrylic; every time we wash our clothes in the washing machine, millions of micro-fibres are shed. It is estimated that one load of clothes in a washing machine releases about 700,000 fibres per wash. A microfibre plastic used in clothes is often thinner than a strand of hair. It passes through washing machine filters and water treatment plants, and ends up in rivers and oceans. When in water, plastic acts like a sponge and absorbs chemicals. Some of these chemicals are products that escaped into the oceans years ago such as DDT, a pesticide, which is now banned.

Human Health

Both microplastics and nanoplastics are potentially hazardous to health. Research in wildlife and laboratory animals has linked exposure to tiny plastics to infertility, inflammation and cancer. The researchers are now testing tissues to find microplastics that accumulated during donors’ lifetimes. Donors to tissue banks often provide information on their lifestyles, diets and occupations, so this may help future work to determine the main ways in which people are exposed to microplastics.

Many of those fibres are consumed by animals at the bottom of the food chain, such as plankton and mussels. Scientists predict it then accumulates up the food chain until it reaches us – although this still needs to be researched. A lot of the plastic pollution is also dispersed by wind and ocean tides, spreading everywhere. So, it’s not just a local problem, but also a global issue. Microplastics pose a risk to humans in three different ways: physical, chemical and as a host for other microorganisms to gather and breed on. It is difficult to assess the details of the risks micro-plastics may pose for humans as each plastic is made up of a unique combination of chemicals. Plastics also come in different shapes, sizes and textures, all of which influence their level of toxicity. Although research on plastics in animals presents a bleak outcome, there is little study undertaken on plastics in the human body and more research is needed.

Reducing Micro-plastics

Wastewater and drinking water treatments can be highly efficient in getting rid of micro-plastics. Studies, albeit limited, show they remove more than 90% of microplastics (although many tiny particles easily pass through water filtration systems and end up in the oceans and lakes, posing a potential threat to aquatic life). These treatments are not available, of course, in many developing countries or impoverished areas or to poorer people. But there is a lot that individuals can do to reduce microplastics too. Perhaps the most important step lies in changing the way we think and behave.

Modern lifestyles are full of single-use plastic items such as straws and cups. It is thought that we use plastic cutlery once for an average of three minutes, but it remains in the environment for hundreds of years. Single-use plastic, including food packaging, is also one of the biggest contributors to plastic pollution. Thinking about how plastic is made and what happens to it after it has been used makes a difference. It must be remembered that plastic offers many benefits to our lives., for instance preventing infections by using plastic syringes and tubes in hospitals and prolonging the shelf life of some food. Care needs to be taken when removing or minimising plastic so that it doesn’t just create a new problem. If we changed from plastic (nylon, polyester) clothing to organic (cotton, wool) clothing, the land and water use needed to grow cotton would be immense. It is therefore a case of pairing alternatives and trying to figure out what the best solution is for each case. The world is now recognising the dangers of micro-plastics; for example, in December 2015, in the USA, President Obama signed the Microbead-Free waters Act banning plastic microbeads in cosmetics and personal care products.

A Pandemic?

Previous studies have shown people eat and breathe in at least 50,000 particles of microplastic a year and that microplastic pollution is raining down on city dwellers. The particles can harbour toxic chemicals and harmful microbes and are known to harm animals. It feels like a pandemic, these small microplastics, analogous to viruses, travelling by water, food and in the air, causing illness and possible death and being worldwide and affecting everyone especially the old and vulnerable. In this case the cause of this international crisis is in our hands but then again, so is the cure.

Alan Potter

Contacts

Chair: Alan Potter

alanspotter@hotmail.com

07713 428670

Secretary: Roger Mitchell

rg.mitchell@btinternet.com

01695 423594 (Texts preferred to calls)

Membership Secretary: Rob Firth

suesmembers74@gmail.com

01704 535914

Forum Editor: Chris Nelson

chris@niddart.co.uk

07960 117719

Facebook: facebook.com/groups/southportues

See our archive for previous editions of the SUES Forum!