Introduction: Remaining in Touch

In these difficult times when, as with other organisations, we have had to suspend our operations for an unknown period, we decided to try to keep SUES alive and in business without actually meeting in person. This Forum is the first of what we hope will be a series of information and discussion publications, designed to keep all our brains ticking over and maintaining SUES’s educational role.

The Forum, which we intend to publish fortnightly, will consist of one or more articles with suggestions for further activity: thinking, investigating and reading. We have called it a Forum, because we are hoping for a response. We would like to receive your comments, further thoughts, suggestions and, if possible, contributions. Some ideas we have for future editions include: book reviews, illustrated articles on American architecture, reminiscences of historical events in our lifetimes, poetry; and there are many more possibilities.

Your responses and ideas should be sent to either Roger Mitchell or John Sharp, whose contact details are given at the end of this edition.

Hermits

(Voluntary Self isolation)

John Sharp

We can all enjoy some solitude on occasions, particularly when we need a break from the pressures of life or are outdoors appreciating an empty, wild landscape. However, compulsory self-isolation, being prisoners in our own home, only occasionally allowed out on licence, is rather something to be endured than chosen. Nevertheless, as we start to find a way to cope with this more limited life-style, we might consider that there were those who deliberately selected the solitary life as a normal form of existence. These were the hermits.

The original meaning of the word was ‘desert-dweller’, because that is where the early Christian hermits were found. They were also sometimes called ‘anchorites’, which is a broader term, meaning those who withdraw from the world. In modern usage ‘a solitary’ is often preferred. We are mostly familiar with hermits in the Christian context, but they can also be found in other religious traditions, particularly Buddhism.

The first Christian hermits are recorded in the deserts of Egypt and the Middle East in the third and fourth centuries AD. They were men, nearly always men, who retreated from social life to live in remote areas, often in caves, where without distractions they could devote themselves to prayer and meditation. They were influenced by the account in the New Testament of Jesus spending time in the wilderness. There was also a sense that this life was a form of penance or self-mortification, to show a denial of the pleasures and comfort of worldly things, to aspire for a purer spirituality. In some cases the retreat into the desert was a way of escaping persecution.

The man regarded as the first hermit was Paul, about whom little is known, other than that he spent his whole adult life in retreat from the world. More famous was his contemporary St Antony, who after a period of some ten years in isolation was then more active in Christian society. The image most often associated with St Antony, and found in traditional pictures of him, is his struggle with the Devil, in the form of temptations that assailed him in his loneliness. Monsters and devils offering the pleasures of the world or in the shapes of beautiful women were a characteristic of the eremitical experience, perhaps not surprisingly so in the light of modern psychological knowledge. Although many hermits did spend their whole lives in the desert, the isolation was not always complete. Some supported themselves by making and exchanging crafts, others were visited for advice, others again acquired bands of disciples.

One of the most spectacular of hermits was Simon Stylites (390-459) who distanced himself from the world on a series of ever-increasingly high pillars, reaching eventually sixty feet. Simon’s motive was pure ascetism. His choice of isolation on a pillar followed a period in a monastery, where his extremes of self-mortification were too excessive to be acceptable. His solution was the pillar, where he could devote himself to exhausting religious exercises and self-denial. Someone once tried to count the number of times he prostrated himself in the course of a day, but lost count after a thousand. The practicalities of life on top of a pillar seem puzzling, but he did have food hoisted up to him and he lived in a sort of basket, presumably so that he would not fall off. There was apparently also some means of fulfilling natural bodily functions, but it is difficult to find the details. The irony was that his isolation attracted such attention that his pillar was often surrounded by crowds of pilgrims and other spectators. After his death his pillar was gradually reduced by people removing chunks as holy relics, but what remains can still be seen today (I’ve been there) in a site near Aleppo in Syria.

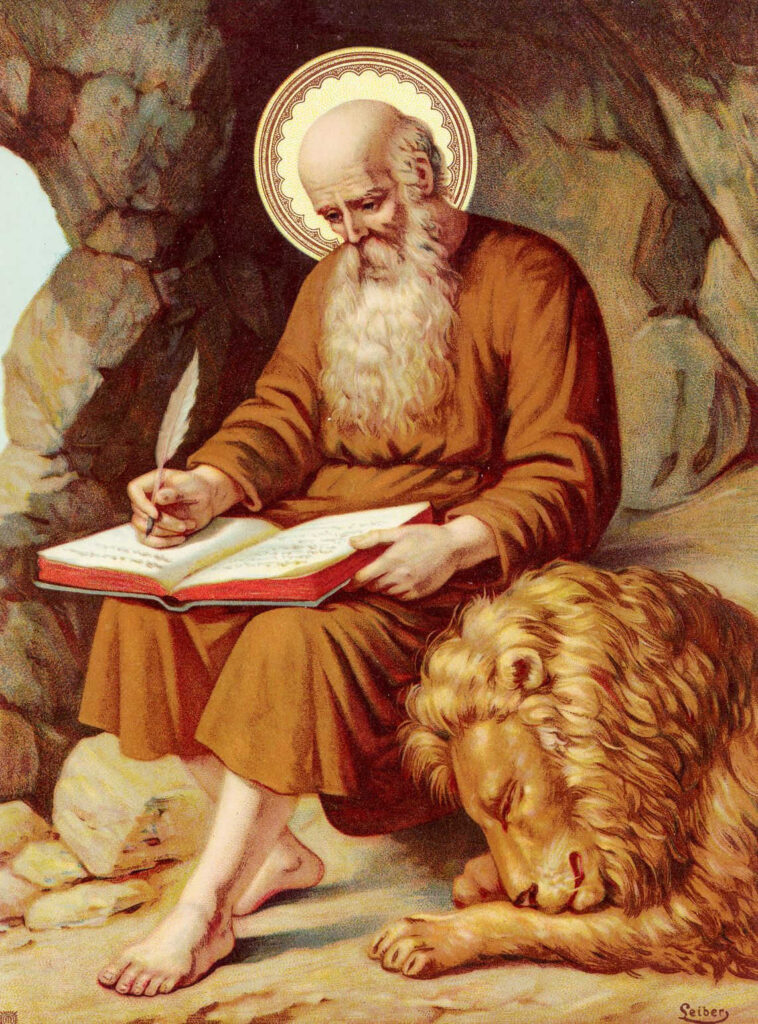

One of the saints of the church most frequently represented in art is Jerome (c347-420). After conversion to Christianity he spent some years in the Syrian desert as a hermit, devoting himself to prayer, study and penance, but thereafter, like St Antony, he was more active in society after being ordained a priest, and finished up as a conventional monk. He is most famous for his translation of the Bible, which became known as the Vulgate, and was for centuries the standard version used by the Catholic Church. One of the most colourful traditions associated with him is that while a hermit he had a tame lion as a pet.

The hermit idea became less fashionable from the fifth century onwards and as a practice it became transmuted into the idea of a monastic community. This came about partly because hermits increasingly found themselves living in areas where there was a cluster of others engaged in a similar life and so it became logical to cooperate. There was also criticism of the life of isolation, which was considered by some to be too concerned with individual salvation and not the welfare of Christians generally. The practice did not entirely die out, however, and over the centuries we can identify others who found that withdrawal from the world was the appropriate spiritual journey. Indeed, the existence of specific rules regulating the lives of anchorites shows that they had some official recognition.

One of these later hermits was a woman, Julian(a) of Norwich (1342-1416), who after being seriously ill received visions which prompted her to spend the rest of her life in isolation. She lived in a cell attached to a Church in Norwich, where she became something of a local celebrity, providing counsel to others as well as living a life of prayer. She was also a notable author, her mystical experiences being published, the most famous being ‘Revelations of Divine Love.’ She is sometimes depicted as accompanied by a pet cat, a somewhat more appropriate creature, one might imagine, than Jerome’s lion.

In the modern times there is still provision for ‘solitaries’ in various religious communities, but there are also what one might describe as ‘secular hermits’, people who have chosen to isolate themselves for reasons that are not or not just religious. Some of these simply find the pace of modern life too exacting, others may be escaping from unhappy personal relationships or emotional turmoil, some simply enjoy life in the wilds.

Is there anything we can learn from the experiences of those who chose self-isolation? We would nowadays probably not look for salvation that way, but perhaps the notion of self-sufficiency is important. We are essentially social beings and many of the fulfilling aspects of our lives involve others. However, the experience of self-isolation may lead us to examine the resources that we have within ourselves and give us the space and time for reflection.

Follow-up suggestions

- Consider the motivation for living a solitary life. You might have thought that a religious inspiration would lead to living and working in the community: ‘love thy neighbour’. Why do some people want to retreat from the world?

- What effect does living alone have on an individual? What are the dangers of living a solitary life?

- You can find out more about individual hermits, such as St Anthony, St Simon Stylites, St Jerome, Julian(a) of Norwich, online or in an encyclopaedia.

- St Jerome was a very popular subject for painters. You might ask yourself why? Find some of these paintings and look in detail at what is portrayed. What is the significance of the various images?

- See if you can find out about hermits in other religious traditions.

Ornamental Hermits and Hermitages

Roger Mitchell

I am afraid that I am going to lower the tone and move from the middle ages to the 18th century and from religion to the country house and its landscape garden. Hermitages were very popular as part of the garden circuit, but, sadly, not very many have survived. It is not surprising really, because hermitages were rustic buildings often of wood or plaster. There were (and in some cases still are) hermitages at Stowe (see pictures below), Badminton, Kedleston, Burley on the Hill, Hawkstone, Brocklesby and Painshill. Dunkeld in Scotland has a particularly fine one. You may well be able to add others.

This Hermitage has been rebuilt as part of the restoration of Painshill. According to Edith Sitwell in English Eccentrics (1933), it was here ‘that the Hon Charles Hamilton, having advertised for a hermit, built a retreat for this ornamental but retiring person on a steep mound. The retreat seems to have been more remarkable for its discomfort than for its beauty, for there was an upper apartment ‘supported in part by contorted legs and roots of trees which formed the entrance to the cell’.

Sitwell has much more to say about hermits, although she is not forthcoming about the sources of her information.

‘Mr Hamilton seems to have had no difficulty in procuring the hermit; and in any case a professional discomfort was only to be expected by the hermit, who, according to the terms of the agreement, must ‘continue in the Hermitage seven years, where he should be provided with a bible, optical glasses, a mat for his feet, a hassock for his pillow, an hourglass for his timepiece, water for his beverage, and food from the house. He must wear a camlet robe, and never cut his hair, beard or nails, stray beyond the limits of Mr Hamilton’s grounds, or exchange one word with the servants. If he avoided breaking any of these conditions, he was to receive, as a proof of Mr Hamilton’s admiration and satisfaction, the sum of £700. But if, driven to madness by the intolerable tickling of the beard or the scratching of the camlet robe, he broke any of the conditions, he was not to receive a penny. It is a melancholy fact that the Ornamental Hermit stayed in his retreat for exactly three weeks!’

She goes on:

‘A gentleman living near Preston, Lancashire had better luck with his hermit. He had advertised in the papers, offering a salary of £50 for life, to any man who would live for seven years underground, without seeing any human being and without cutting his hair, beard, toe nails or finger nails. The advertisement was answered immediately and the happy advertiser prepared an apartment underground which was ‘very commodious, with a bath, a chamber organ, as many books as the occupier pleases and provisions served from the gentleman’ own table’. The occupant bloomed unseen for the space of four years.’

Her final examples are:

‘The following notice appeared in The Courier for Jan 11th, 1810 – ‘A young man who wishes to retire from the world and live as a hermit in some convenient spot in England, is willing to engage with any nobleman or gentleman who may be desirous of having one. Any letter directed to 6, Coleman Lane, Plymouth, mentioning what gratuity will be given, will be duly attended.’

The mention of the gratuity sounds a little mercenary and it is not known how many letters arrived.

‘In Blackwood’s Magazine in 1830, Mr Christopher North informs us that the editor of a certain other magazine had been ‘for 14 years hermit to Sir Richard Hill at Hawkstone and sat in a cave in that worthy Baronet’s grounds with an hour glass in his hand, and a beard belonging to an old goat, from sunrise to sunset, with orders to accept no half crowns from visitors, but to behave like Giordano Bruno.’

Follow up suggestions

- I don’t understand the reference to Giordano Bruno. He was a 16th century Italian philosopher, scientist and ‘occultist’ who was burned at the stake for Heresy by the Inquisition in Rome.

- I would love to know who ‘the gentleman from Preston’ was.

- How seriously should we take this? I note that The Hawkstone Hermit only worked limited hours.

Contacts

Chair: Alan Potter

alanspotter@hotmail.com

07713 428670

Secretary: Roger Mitchell

rg.mitchell@btinternet.com

01695 423594 (Texts preferred to calls)

Membership Secretary: Rob Firth

suesmembers74@gmail.com

01704 535914

Forum Editor: Chris Nelson

chris@niddart.co.uk

07960 117719

Facebook: facebook.com/groups/southportues

See our archive for previous editions of the SUES Forum!